- Startseite

- Publikationen

- GIGA Focus

- Ten Things to Watch in Africa in 2024

GIGA Focus Afrika

Ten Things to Watch in Africa in 2024

Nummer 1 | 2024 | ISSN: 1862-3603

Democracy will remain under pressure in Africa, with key elections coming up in 2024. While conflict risks could intensify, the decline of Western influence will continue. Structural socio-economic challenges are likely to persist despite economic growth. The Africa Cup of Nations will be a highlight at the beginning of the year. We present here a list of “Ten Things to Watch in Africa” in 2024.

Politics: With the recent wave of military coups, democracy has come under pressure. Further coups remain a risk, especially in countries with politicised militaries and political crises. Important general elections will, inter alia, be held in Ghana and South Africa where heavy losses for the ruling parties are expected.

Peace and security: Coups are often connected to armed conflicts. The spillover of jihadism and related ethno-regional tensions in West Africa will be a major security challenge. In the Horn of Africa, the ceasefire in Ethiopia’s Tigray Region seems to be holding but the country remains instable.

Internationally: Similar to Russia’s war on Ukraine, the Israel–Hamas conflict also divides African governments. The relative decline of Western influence is likely to continue, not least regarding military presence. Growing anti-immigration sentiment in Europe has made migration a salient issue in African–European relations.

Socio-economic development: African economies are set to experience continued growth that will, however, vary across countries, while debt remains a formidable challenge. Green deals are likely to remain sluggish.

Policy Implications

Many pressing challenges need to be resolved primarily by African governments and societies, such as addressing the root causes of coups and conflicts. Germany and Europe should prioritise developing a coherent Africa policy. Migration policies should seek win-win solutions rather than “containment.” Artificial intelligence represents an opportunity but also poses disinformation risks.

Election Watch 2024: Post-Coup Countries Face Hurdles to Democracy

Sub-Saharan Africa gears up for an eventful electoral year in 2024. At least 16 countries are set to hold presidential, legislative, and local elections (see Figure 1 below). The cycle starts with Comoros and Senegal holding presidential elections, followed by Mauritania, Rwanda, and Mozambique, among others. While Senegalese President Macky Sall declared that he would not pursue an – unconstitutional – third term, Rwandese President Paul Kagame runs for a fourth term – as enabled by a constitutional change in 2015. In Mozambique, President Filipe Nyusi’s quest for a controversial third term may spark social unrest. At the time of writing, provisional results from the Democratic Republic of Congo’s presidential elections have placed incumbent President Felix Tshisekedi in a commanding lead for a second term. The opposition is reacting strongly, alleging widespread irregularities and demanding result annulment. This dispute, coupled with waning trust in state institutions, risks exacerbating instability in the country, particularly in its volatile eastern region. Elections in coup-affected Chadand Mali will most likely also be a source of concern, whereas prospects for elections in some of Africa’s (former) “poster child” democracies are more mixed.

In Burkina Faso, where elections had originally been scheduled for 2024, junta leader Ibrahim Traore recently suggested that they are not a priority compared to security. In Chad, amid recurring postponements of legislative elections since 2015 and a coup in 2021, plans are now afoot to combine these delayed polls with presidential and local elections in 2024. In Mali, presidential elections are scheduled for February. While these post-coup elections could signify a turnaround, crucial conditions necessary for credible elections – such as press freedom, voter security, and institutional safeguards on fair competition – are sorely lacking. This shortfall may result in flawed electoral processes, hindering the success of the transition to democracy. Challenges such as limited international media presence and strict domestic media censorship in Chad may foster malpractice and concealment; Mali, meanwhile, faces concerns about voter security due to the Islamist insurgency in the north and opaque constitutional reform.

Botswana, Ghana, and South Africa, relatively stable democracies in Africa, are also gearing up for elections in 2024. In Botswana, the dominant BDP (Botswana Democratic Party) faces formidable challenges. The same is true for South Africa, where the ANC (African National Congress) could lose its absolute majority (see“South Africa at a Crossroads”below). Polls in Ghana predict victory for the opposition (National Democratic Congress), as the domestic population is dissatisfied with poor public services and declining living standards. While this change in power may heighten political tensions, the country is expected to successfully manage the handover as done in the past.

Figure 1. Elections in Sub-Saharan Africa in 2024

Source: Authors’ own compilation.

South Africa at a Crossroads

Undoubtedly, South Africa faces a major test of its democratic credentials in its 2024 national and provincial elections. These polls include several firsts for the electorate. This year is the first time that independent candidates can run in provincial and national elections. It is also the first time that the ANC might lose its absolute majority since the transition from Apartheid in 1994. Significantly, it is furthermore the first time that there might be a coalition government presiding over the state. Survey results predict that the ANC will only secure 45 per cent of the vote (Social Research Foundation 2023). The official opposition, and centrist party, the Democratic Alliance (DA) is predicted to attain 31 per cent thereof. The populist radical left party, the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), is the third-biggest party and is expected to achieve 10 per cent of the vote.

Who, then, will the ANC invite to be their bedfellows? The EFF is considered the most likely coalition partner here. However, the DA has declared that they will do everything possible to prevent this from occurring. To this end, the DA and several other “like-minded” opposition parties have joined together in a coalition called the Multi-Party Charter (formerly, the Moonshot Pact). Yet, opposition parties have historically been unable to capture the vote from the public despite their disillusionment with the ANC. Those eligible are choosing not to cast their ballot at all, rather than favouring an alternative to the ANC – as indicated by the steadily decreasing voter turnout since 1994.

Scepticism abounds about whether South Africa’s democratic system is ready for the instability associated with coalition governments. Persistent violent crime, entrenched xenophobia, astronomically high levels of inequality and poverty, high-profile corruption cases in the public and private sectors, and rolling power blackouts have left the South African public weary and the outlook bleak. The rainbow nation needs inspiration and hope. Perhaps coalition politics will help revitalise voters’ interest in the power of their ballot and reignite the spirit of democracy.

The Future of Military Regimes in the Sahel

The political landscape of the Sahel countries has yet to reach a new equilibrium. Following coups d’états in Mali in August 2020 and May 2021, in Burkina Faso in January and September 2022, and in Niger in July 2023, military juntas have been working to consolidate their power and re-orient their countries’ international relations. But outside the respective capital cities, the crisis is growing – militarily, economically, and from a humanitarian point of view too. In post-coup Niger, ECOWAS sanctions have hit the economy hard. Some 40 per cent of the national budget has evaporated. Imported goods have become scarce and expensive. Food and fuel prices have skyrocketed. Citizens feel the pain – yet many continue to publicly support the military junta, while pro-democracy voices are increasingly silenced.

In Mali, stability has deteriorated fast. After the withdrawal of French troops in 2022, the junta expelled the UN stabilisation mission MINUSMA in June 2023. The peace process between the government and Tuareg rebel groups broke down, leading to large-scale fighting in which Russian mercenaries are playing a central role. The resurgence of the civil war ultimately benefitted jihadists, whose influence now extends to large parts of northern and central Mali. By May 2023, the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) had captured the Ménaka region along the border with Niger. Since August 2023, the city of Timbuktu has been under siege by Jama'at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM). JNIM has also been strengthening its foothold in the southern regions of Koulikoro and Kayes (Ani 2023), bringing the conflict dangerously close to the capital Bamako. The junta is continuing to consolidate its power, but the conflict is spiralling out of control and the risk of state collapse is palpable.

In Burkina Faso, the military junta continues to enjoy significant public support, but its strategy of full-blown warfare against jihadists has so far failed to improve the dramatic security and humanitarian situation in the country. By mid-2023, 46 towns and cities were under siege by jihadists (Amnesty International 2023), who control roughly 40 per cent of the national territory. The humanitarian consequences are immense. Roughly two million people are internally displaced; hundreds of thousands living in blockaded cities. Throughout the country, civilian self-defence militias have taken up arms, exacerbating the risk of inter-ethnic violence. The regime is reacting increasingly nervously to any opposition; repression against journalists and civil society has intensified. Burkina Faso is a society in disequilibrium, caught in the centre of an overwhelming regional crisis, but emphasising self-reliance.

While Mali and Burkina Faso formally have transition agreements with ECOWAS, the question remains how much these commitments are worth. The military regimes continue to depend on public support (Lierl 2023) but seize every opportunity to consolidate their power. Should they lose the backing of their respective populaces, the transition charters provide them with an exit strategy. In Niger, the junta has taken the most extreme stance against ECOWAS. With Togolese mediation, however, the confrontation between the junta and ECOWAS is slowly beginning to de-escalate. By the end of 2023, Niger was inching closer to a transition agreement that may present an opportunity for ECOWAS to lift its sanctions.

Coups and Conflict Risks amid Western Withdrawal

Military coups regularly happen in countries with a traditionally politicised military that intervenes in times of political crisis and when the population is dissatisfied with civilian politicians. In the Sahel, these crises connect to the “jihadist wave” that has spread to coastal states such as Benin and Togo and also threatens other countries like Cote d’Ivoire or even Ghana. Worryingly, jihadism often capitalises on ethnic tensions and then exacerbates them. The spread of jihadism coincides with the continued withdrawal of international missions and Western military. As a result, observers fear the worst for regional security. The UN lowered its flag in Mali at the end of December 2023, bringing an official close to its peacekeeping operation in the country while French troops had already left the country the year before. Following the coup in Niger in July 2023, the French military is now also set to withdraw from this Sahelian country whereas the US has accepted the new reality and will maintain a military presence there for the time being. As France’s influence in Africa rapidly wanes, Russia is seeking to increase its military presence and to deepen other forms of engagement on the continent by capitalising on anti-French and partially anti-Western sentiment.

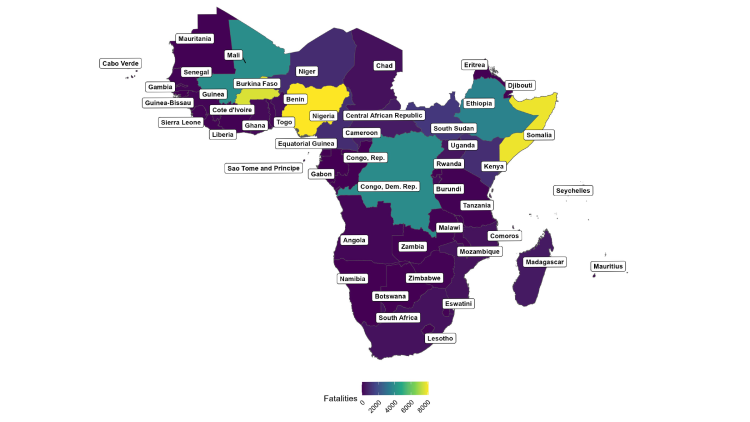

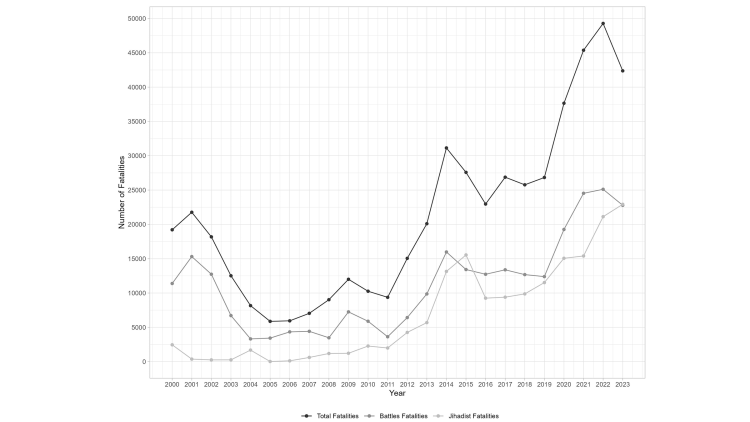

While jihadism represents a growing transnational threat, many other countries face more mundane conflict risks (see Figures 2 and 3 below). A relatively young population in global comparison alongside widespread dissatisfaction with governments and civilian politicians might spur protests, riots, and coups. Ethno-regional and secessionist conflict risks remain rampant, not least in Central Africa as well as the Horn of Africa. The continent’s most intense recent war took place in Ethiopia. The conflict in the Tigray Region claimed at least 100,000 lives – which explains the peak in Figure 3 below – but seems to have come to an end. Yet, armed clashes in the Amhara Region continued in 2023. Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed recently made worrying remarks that may spark new tensions. He stated that if his country did not manage to secure direct access to the Red Sea, this might lead to violent conflict with Ethiopia’s neighbours.

Generally, conflict risks need to be watched closely – ideally before violence erupts. West Africa especially, but many other parts of the continent too, will be a testing ground for such preventive policies that tackle violent conflict before it breaks out. Donors, international organisations, and African governments and societies all need to live up to the challenge here.

Figure 2. Conflict Fatalities in Sub-Saharan Africa in 2023

Source: Authors’ own compilation, based on ACLED (2023).

Notes: Numbers consider data until 9 December 2023. The figure was created by Fredric Lüssenheide.

Figure 3. Conflict-Intensity Trends in Sub-Saharan Africa since 2000

Source: Authors’ own compilation, based on ACLED (2023).

Notes: Numbers consider data until 9 December 2023. The figure was created by Fredric Lüssenheide.

The German Government’s Multi-Faceted Africa Policy

In the second half of 2023, the German government’s foreign policy focus was on Hamas’s 7 October terrorist attacks and the subsequent Israeli response. It is also an important issue on the African continent. As the conflict continues, it has the potential to affect relations between Germany and its partners in Africa, as the latter’s countries remain deeply divided over Israel and Palestine. The question of whether Israel should be granted observer status to the African Union, for example, has been a point of contest for more than a decade now. South Africa’s government has been a vocal critic of Israel’s response to the terrorist attacks and recently filed a case at the International Court of Justice accusing Israel of “genocidal acts” in Gaza.

Germany’s Africa policy has now clearly moved beyond sole focus on development. The federal government announced that it will further develop its Africa policy guidelines – and several high-level visits to the continent signalled its intent to bolster diplomatic ties and economic partnerships with Africa. Chancellor Olaf Scholz travelled to Nigeria and Ghana in October, which was already his third trip to Africa in the two years since he assumed office. During these visits, several themes that will remain high on the agenda for 2024 were addressed: namely, migration, security in the Sahel, private investment, energy partnerships, and Germany’s colonial past. The German government is seeking to foster closer collaboration to “manage” migration – for example, by expanding the so-called migration centres that are supposed to support returnees from Germany.

“Africa” was not the focus of Germany’s first comprehensive security strategy, which was released in June last year (Grauvogel 2023). Yet, the German government will remain pre-occupied with dealing with the fallout of the coup in Niger. The Bundeswehr’s departure was completed in December 2023 but the underlying question of how, going forward, Germany will continue to engage in the Sahel region remains. During the most recent Compact with Africa Conference, the green energy transition – for example, via the production and export of hydrogen – and the creation of jobs through private sector investment were key foci. Yet, the deepening of partnerships with African countries will not only depend on whether Germany can make sufficiently attractive economic offers to them. President Frank-Walter Steinmeier apologised for killings in Tanzania under Germany’s colonial rule when he visited the country in October. But Germany has to do more to rectify the legacies of its erstwhile imperial presence on the continent: initiatives to return human remains, for example, need to be intensified.

Macro-Economic Development: Strong East African Growth, But Uncertainty Looms

After a rather difficult year for many African economies, the economic outlook for 2024 is better – albeit some countries will fare much better than others. African economies are predicted to grow on average by 3.2 to 4 per cent, up from 2.6 per cent and 3.3 per cent respectively (EIU 2023; IMF 2023) – but these rates are still lower than those projected for emerging and developing countries in Asia. There are, though, bright spots: the Economist Intelligence Unit (2023) predicts 12 of the world’s 20 fastest-growing economies to be found in Africa, including Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania, and Uganda. East Africa thus remains the continent’s best-performing region – as driven, interestingly, by the service sector not commodity exports. The two heavyweights Nigeria and South Africa will again grow too slowly at 3.1 and 1.8 per cent, respectively. Nigeria’s population growth of roughly 2 per cent per annum implies very slow economic progress in per capita terms.

Growth also remains low in Ghana, one of Africa’s poster child economies. Two important risks that also affect other African economies are highlighted by this country case. First, inflation is projected to remain above 20 per cent annually – albeit down from about 40 per cent in 2023. Although inflationary pressures are easing across the continent, Ethiopia, Nigeria, and several other countries will also continue to struggle with two-digit inflation rates. Second, Ghana’s debt stood at 90 per cent of its GDP in 2022 – with debt service exceeding government revenue that year. Under the ongoing restructuring scheme, debt is projected to decline to about 80 per cent in 2024 – but uncertainty about progress here increases overall economic uncertainty.

Debt issues also plague other African economies. On average, the continent’s countries spend more than one-fifth of their revenue on debt servicing. Those under debt distress also include Malawi, Mozambique, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. The induced economic uncertainty and the restricted access to finance depresses growth in these countries unless it is mainly driven by a resource boom, as in Mozambique. Access to finance remains difficult even beyond these particular countries. Interest rates on international capital markets will remain high, thus generally limiting access to capital for much-needed private and public investment. This situation is compounded by a sharp decline of Chinese financial investment in Africa, which is unlikely to recover any time soon from the low levels that it reached during the COVID-19 pandemic. Difficult external conditions, debt issues, plus the outlined political uncertainties together add up to a mixed outlook for 2024.

Green Projects in and for Development: Opportunities and Obstacles

It has become apparent in the past few years that Africa will play various roles in the world’s path towards a low- or zero carbon energy system. The year 2024 will yet be another one during which these roles take shape. They are heavily dependent on specific countries’ endowments, in particular regarding the potential for renewables, the minerals needed for the global energy transition, and the forests or other land that can be converted into carbon credits. Turning those “climate assets” into development and prosperity is a great challenge. While optimists see here the chance to kick-start the continent’s “green industrialisation,” pessimists point out that many such opportunities have already been wasted in the past and ask why it should be any different this time around. Indications of where these developments are headed can be gained by watching carefully what happens with certain big projects that are emblematic of what might become another “scramble for Africa.”

It is estimated that current climate pledges and commitments will require millions of hectares of land to offset carbon through nature-based solutions, including through reforestation and conservation projects. Africa is becoming a hotspot of such endeavours. United Arab Emirates-based company Blue Carbon made headlines in late 2023 after striking deals apparently securing the rights to issue carbon offsets based on areas covering millions of hectares in Kenya, Liberia, Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. Such deals are likely to pose a threat to communities’ land rights, local food security, and personal livelihoods. This is why these developments must be closely monitored by journalists, NGOs, and researchers. Only strict standards for carbon-offsetting projects (to be traded internationally) are likely to turn them into a development opportunity for the affected communities and indeed continent at large.

Another sector worthy of observation is “green hydrogen.” Several countries in Africa – among them Kenya, Mauritania, Namibia, and Senegal (plus Egypt and Morocco in North Africa) – have plans to produce hydrogen/ammonia using their renewable potential. Many such projects are currently in the planning phase, seeking to acquire (more) funding and, eventually, secure contracts for future exports. It will thus take time for countries to produce and export green hydrogen: Hyphen’s ambitious project in Namibia, for example, plans to export two million tonnes of green ammonia from there to Europe before the end of the decade.

Beyond these grand plans, internationally somewhat less visible green projects are in the making in Africa’s transport sector, too. While these endeavours may not matter a great deal to global emissions (transport accounts for about 5 per cent of Africa’s greenhouse gas emissions; deforestation for about 45 per cent), they may, at least, help avoid lock-ins into carbon-intensive transport systems and relieve people’s daily plight of being stuck in traffic in Africa’s major cities. Dakar’s Bus Rapid Transport system is meant to start operating in 2024 and Abidjan has plans for a similar system, with construction work due to begin in 2024. Yet, similar plans in Accra have previously failed; as such, it remains to be seen whether these ambitious plans can actually be realised.

From Brain Drain to Win-Win: Can African Countries Get a Better Deal on Migration?

Migration from Africa to Europe is set to remain a necessity and a reality for decades to come: European countries face a double burden of ageing societies and severe shortages of (skilled) workers, while African economies create too few sound jobs for their youthful populations. Yet, growing migration numbers and populism in 2023 have fuelled increasing anti-immigration sentiment in Europe, translating into policies focused on curbing irregular migration. Most extremely, the UK government is planning to deport a number of those arriving without a valid visa to Rwanda and have them apply for asylum there instead. Under pressure at home, other European politicians have been attempting to negotiate deals in which African governments commit to assisting with the identification and repatriation of migrants. Their limited success highlights that European governments have so far failed to present attractive migration deals that convincingly maximise the benefits – such as skill transfers and remittance payments – and mitigate the risks – such as brain drain – for African countries themselves.

Ghana’s health sector illustrates the tug of war playing out over who gets the most qualified personnel: some 4,000 Ghanaian nurses, often highly specialised and experienced, emigrated to work abroad in 2022 alone – even though the country’s “red-list” status indicating severe medical staff shortages prevents active recruitment from abroad. The UK government sparked outrage with reports that it was negotiating a deal to recruit these nurses directly, promising Ghana meagre compensation of GBP 1,000 per individual. Strengthening and expanding legal migration pathways, a necessary first step towards a win-win solution, thus needs to be combined with a stronger focus on training up the skilled staff everyone needs. If European countries want African IT specialists, doctors, and engineers, they need to be ready to invest in their training. And African countries will only be able to keep valued specialists if they address the poor working conditions that make them leave in the first place. The year ahead will show whether African governments can turn a crisis into an opportunity for a better deal on migration.

African Digitalisation in 2024: Leapfrogging to Le-AI-Pfrogging?

The year 2024 promises the proliferation of artificial intelligence-powered products across a range of public and private entities in Africa. Smart agriculture offers AI-powered drones monitoring crops for pests and diseases plus crop yield prediction via the Africa Agriculture Watch platform’s satellite remote sensing. In the field of medicine, Nigerian company EpochZero aims to overcome the shortage of radiologists (1 per 600,000 people) by allowing AI to read and interpret X-rays. AI-personalised learning, such as Mtabe in Tanzania, tailors education to each student, including the use of minority local languages – a major issue on the continent until now. The already-booming digital finance ecosystem, led by Nigerian success story Flutterwave, should receive an AI-powered advancement along with other uses in retail, tourism, and manufacturing.

This potential stands against a backdrop of insecurity about AI replacing workers on a continent where approximately half a billion more jobs need to be created by 2050. Some of these concerns are not unique, such as AI taking Nollywood jobs, but others are more specific to Africa per se. Tens of thousands of Africans are precariously employed by Big Tech firms to carry out the categorisation tasks that power AI, alongside reviewing toxic content – as required to fine-tune safety mechanisms (Perrigo 2023). The continued existence of those jobs becomes a race against time in the face of the very AI that they are powering, with workers needing to upskill their knowledge so that they can offer marketable services going forward.

Another battlefront in 2024 will be the fabrications that AI helps amplify in an already misinformed digital space. Following on from deepfake videos in Burkina Faso urging people to support the junta, more examples of disinformation, cyber harassment, deepfake sextortion, and elaborate scams are to be expected. African governments are likely to move beyond digitalising identity, postal systems, and taxation to address also cybersecurity so as to better prevent AI-enabled cyberattacks. Since global AI rules have begun to be decided without their involvement, African hubs are likely to demand inclusion in AI standard-setting discussions. The promise of AI relies on improved ICT infrastructure – a competitive space for the US, China, and Europe. Therefore, further international deal-making around digital infrastructure plus appeals for greater African sovereignty over such matters will take prominence in 2024.

Football Fever in Africa and Europe

Because of adverse weather conditions in the summer of 2023, the Africa Cup of Nations (AFCON) was postponed to January 2024. The year ahead will thus see both the Euros hosted in Germany (in June/July) and AFCON in Côte d’Ivoire (in January/February). The timing of the latter has been contested, as it falls amid the European football season. This has led to conflict between the mainly European employers of many African star players and their national teams. It seems, however, that these issues have been largely resolved, with the players in question being released by their respective clubs. Football fans on the two continents have the dates and the times of the games blocked and are eagerly looking forward to the matches. According to recent betting odds, people appear to think that the Cup will most likely go to Senegal, then Algeria or Morocco.

Available studies on the multi-faceted economic impacts of hosting mega sports events yield ambiguous findings. Doing so may be in the interest of fans, but not a good idea economically. Two key cost factors here are public investment in infrastructure that is not necessarily needed afterwards but also private investment that creates overcapacity. Côte d’Ivoire is hosting AFCON for the first time since 1984, which necessitated some investment in stadiums and their renovation. The Stade Olympique Alassane Ouattara d’Ebimpé stands out here. Inaugurated in 2020, it is among West Africa’s biggest stadiums with a capacity of 60,000 – having cost an estimated EUR 200 million.

Overall, neither football event seems to have led to excessive and unnecessary investment in public infrastructure. One clear winner is the hospitality sector. Some 1.5 million guests are expected for AFCON, while Berlin alone expects about 2.5 million for the Euros. A quick look at hotel rates reveals that peak demand drives prices. In Abidjan, the effect appears moderate with hotel prices roughly doubling; in Berlin, however, the increase is even steeper. Getting into stadiums for the Euros will require quite some luck, as demand exceeds supply several times over. At the time of writing, a decent number of tickets were still available for AFCON. Ticket prices range from XAF 5,000 (about USD 8) to XAF 15,000 FCFA (about USD 24). This implies that the cheapest tickets would be available for what is approximately 0.3 per cent of Ivorians’ average annual income.

This GIGA Focus deviates from the series’ typical format. It is the joint product of several GIGA Institute for African Affairs staff members. Martin Acheampong and Julia Grauvogel authored the election-watch section. Maxine Rubin wrote the contribution on South Africa’s upcoming polls; Malte Lierl wrote on the military regimes in the Sahel; Matthias Basedau authored the segments on violent conflicts to which Nicole Hirt (Ethiopia) and Fredric Lüssenheide (figures) also contributed. Christian von Soest and Julia Grauvogel wrote the section on the German government’s Africa policy. Jann Lay, with some input from Lena Merkel, outlined the macroeconomic challenges. He also authored the pieces on “green deals” and the Africa Cup. The latter section also includes input by Tabea Lakemann. Tabea is the author of the section on migration. Andrew Crawford wrote the piece on digitalisation. Jann Lay, with some input by Tabea Lakemann authored the contribution on migration. Martin Acheampong and Julia Grauvogel as well as Matthias Basedau – as editor of GIGA Focus Africa series – edited this Focus.

Fußnoten

Literatur

ACLED (Armed Conflict Location and Event Dataset), Dashboard, accessed 19–22 December 2023.

Amnesty International (2023), Burkina Armed Groups Committing War Crimes in Besieged Localities, 2 November, accessed 29 December 2023.

Ani, Christian Ndubuisi (2023), Economic Warfare in Southern Mali Intersections Between Illicit Economies and Violent Extremism, OCWAR-T Research Report 13, November, accessed 5 January 2024.

EIU (Economist Intelligence Unit) (2023), Africa Outlook 2024. Strong Growth Amid Heated Elections and Financial Woes, accessed 29 December 2023.

Grauvogel, Julia (2023), Africa’s Marginal Role in Germany’s First National Security Strategy, GIGA Focus Africa, 6, December, accessed 18 December 2023.

IMF (2023), Regional Economic Outlook, Sub-Saharan Africa, October 2023: Light on the Horizon?, 10 October, accessed 29 December 2023.

Lierl, Malte (2023), Siding with Societies: How Europe Can Reposition Itself in the Sahel, GIGA Focus Africa, 5, December, accessed 18 December 2023.

Perrigo, Billy (2023), Exclusive: The $2 Per Hour Workers Who Made ChatGPT Safer, in: Time,18 January, accessed 29 December 2023.

Social Research Foundation (2023), South Africa’s Political State of Play in October 2023, Report 45/2023, accessed 27 November 2023.

Redaktion GIGA Focus Afrika

Lektorat GIGA Focus Afrika

Forschungsprojekt

Regionalinstitute

Wie man diesen Artikel zitiert

Acheampong, Martin, Matthias Basedau, und Julia Grauvogel (2024), Ten Things to Watch in Africa in 2024, GIGA Focus Afrika, 1, Hamburg: German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), https://doi.org/10.57671/gfaf-24012

Impressum

Der GIGA Focus ist eine Open-Access-Publikation. Sie kann kostenfrei im Internet gelesen und heruntergeladen werden unter www.giga-hamburg.de/de/publikationen/giga-focus und darf gemäß den Bedingungen der Creative-Commons-Lizenz Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 frei vervielfältigt, verbreitet und öffentlich zugänglich gemacht werden. Dies umfasst insbesondere: korrekte Angabe der Erstveröffentlichung als GIGA Focus, keine Bearbeitung oder Kürzung.

Das German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) – Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien in Hamburg gibt Focus-Reihen zu Afrika, Asien, Lateinamerika, Nahost und zu globalen Fragen heraus. Der GIGA Focus wird vom GIGA redaktionell gestaltet. Die vertretenen Auffassungen stellen die der Autorinnen und Autoren und nicht unbedingt die des Instituts dar. Die Verfassenden sind für den Inhalt ihrer Beiträge verantwortlich. Irrtümer und Auslassungen bleiben vorbehalten. Das GIGA und die Autorinnen und Autoren haften nicht für Richtigkeit und Vollständigkeit oder für Konsequenzen, die sich aus der Nutzung der bereitgestellten Informationen ergeben.