- Home

- Publications

- GIGA Focus

- Siding with Societies: How Europe Can Reposition Itself in the Sahel

GIGA Focus Africa

Siding with Societies: How Europe Can Reposition Itself in the Sahel

Number 5 | 2023 | ISSN: 1862-3603

The swift rise of military juntas in the Sahel, their alignment with Russia, and their adept use of anti-colonial and anti-French rhetoric have left many in Europe grappling for answers. Was Europe’s engagement in the Sahel in vain? How should Europe position itself vis-à-vis the new military regimes?

The withdrawal of European engagement in the Sahel has fuelled narratives of sovereignty and anti-colonial emancipation. However, the populist rhetoric of the military juntas masks a more complex reality: they govern fragile states, with the social order in flux. Their power is tenuous, hinging on fleeting public support and the acquiescence of elites.

The military juntas continue to enjoy significant public support. Their support is driven by a combination of populism, militarism, conflict aversion, and sheer desperation. However, beyond the hard-to-fulfil promise of regaining control over the security situation, the military juntas have little to offer to society. If public dissatisfaction grows, they have to choose between ramping up repression or eventually relinquishing power.

While African societies have not lost their preference for democracy, public opinion has become more divided. Unconditional support for democracy is nowhere near the supermajority it was a few years ago, but it is still dominant in all Sahel countries except for Mali.

Policy Implications

Confronted with the military rulers’ anti-Western stance, European foreign policy should focus on societies instead of governments. In the past, Europe discredited itself by relying on dialogue with governments, without adequately considering the broken feedback loop between governments and societies. Going forward, Europe should ensure that its engagement is understood and supported by broad majorities.

The End of Europe in Africa?

For decades, Europe has prided itself on championing democracy, human rights, and the rule of law in its foreign policy towards Africa. However, the recent wave of military coups in Guinea, Mali, Sudan, Burkina Faso, and Niger have caught European policymakers off-guard. The swift rise of military juntas, their adept use of anti-colonial and anti-French rhetoric, and their surprising ability to rally public support have left many in Europe grappling for answers. In public discourse, the narrative that Europe is losing its foothold in Africa is gaining traction, while anti-democratic powers like Russia and China appear to be expanding their influence on the continent.

But is this the end of Europe in Africa? Are African societies truly drifting away from democratic ideals? The populist rhetoric of the military juntas might suggest so, but it masks a more complex reality. Beneath the surface, there is a profound crisis of state–society relations. These military regimes are far from consolidated. They govern fragile states, with the social order in flux. Despite their bravado, the power of the military juntas is tenuous, hinging on fleeting public support and the acquiescence of elites.

This is where Europe’s opportunity lies. Instead of merely reacting to the changing geopolitical landscape in Africa, European governments should think ahead. They should align their foreign policy with the aspirations of African societies. Europe should invest in understanding their desires and position itself politically in ways that resonate with broad majorities in the targeted societies. Promoting democracy in Africa is not about exporting European institutions. It is about listening, understanding, and respecting majority opinions and minority rights in ways that neither the military regimes nor indeed non-democratic powers like Russia and China are capable of.

Focusing on West Africa and the Sahel, this essay will discuss the recent wave of military coups from the perspective of state–society relations. This will involve delving deeper into public attitudes towards democracy and military rule, the narratives of sovereignty and anti-colonial resistance that have fuelled the recent coups, and the political sustainability of military rule in the Sahel. Finally, a path forward will be charted for European foreign policy – one that sets it apart from its geopolitical rivals Russia and China, without engaging in a bidding war for the favour of military rulers.

Beneath the Surface: A Long-Standing Crisis of State Legitimacy

Long before the current wave of coups, the countries of the Sahel region had been struggling with deeply problematic state–society relations. At the core of this problem lies unequal access to political-interest articulation. Politicians and institutions lacked orientation towards citizens’ needs and preferences. It was more promising for politicians to serve the narrow interests of elites than to do the hard work of reconciling conflicting interests in society. The disconnect between the political system and the everyday lives of the younger generations, the rural majority, and other non-elites resulted in a legitimacy deficit that became apparent long before the recent turn of events.

The causes of that legitimacy crisis are multifaceted and have deep historical roots. Research on African politics has pointed to the legacies of colonial institutions of domination and extraction, the dominance of informal power networks over formal institutions, ethnic and religious identity politics, unequal state presence between urban versus rural areas, the power of older, urban elites over an increasingly youthful society, the lack of a monopoly on violence, corruption and predatory behaviour by state authorities, an unaccountable security sector, aid dependence, and so forth. While the severity of these problems varies across countries, their consequences are ultimately similar: a broken feedback loop between citizens and elites.

Elections alone were insufficient to guarantee the legitimacy of civilian governments (Lierl 2021). Citizens had little stake in a political process that many perceived as morally bankrupt. With respect to Mali, Cravens-Matthews and Englebert (2018) went as far as describing the entire polity as a “Potemkin state” – that is, a façade used opportunistically for the purpose of managing international support and political transactions, but detached from the informal processes of political decision-making and the reconciliation of competing interests.

Foreign assistance and diplomacy played their own parts in the legitimacy crisis, by acting on the false premise that elected civilian governments would faithfully represent societal interests (Lierl 2020). Instead of reassuring themselves that their goals and assumptions were supported by society, Western governments maintained the fiction that a fully sovereign, legitimate partner government was “in the driver’s seat.” In doing so, European governments overlooked the fact that the civilian governments they were partnering with were themselves part of the problem. During the recent coups d’état, military and political elites, civil society, and ordinary citizens proved themselves unwilling to mount meaningful resistance. This acquiescence must be understood in light of the already-damaged legitimacy of the preceding elected governments.

Have African Societies Lost their Preference for Democracy?

Not long ago, large societal majorities across the region unconditionally preferred democracy over any other form of government. Pro-democratic revolutions in Burkina Faso in 2014 and Sudan in 2019 energised civil society across the African continent. What happened, then, to African societies’ preference for democracy? While representative data remain scarce, the few sources that are available paint a complex picture here.

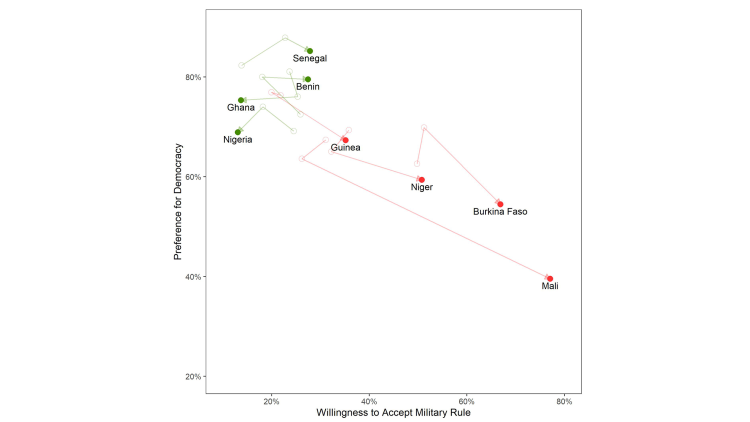

Figure 1. Preferences for Democracy and Willingness to Accept Military Rule, 2018–2023

Source: Author’s own elaboration, with population-weighted data from Afrobarometer Round 7 (2018/19) – Round 9 (2022/23).

Representative data from the 2022/23 round of Afrobarometer surveys in Guinea, Niger, Burkina Faso, and Mali suggest that the recent wave of coups d’état was accompanied by a significant shift in public opinion (Figure 1). In these countries, public sentiment has become much more divided of late. Unconditional support for democracy is nowhere near the supermajority it was a few years ago, but it is still dominant in all Sahel countries except for Mali. It is possible that a greater sense of caution under the new regimes could have affected survey responses, but it would be wrong to dismiss this downward trend as mere measurement error.

Even prior to the coups d’état, citizens’ preference for democracy had never fully translated into a rejection of military rule. While the share of the population approving of military rule used to range between 10 and 35 per cent in most countries of the Sahel region, a majority of people in Niger, Burkina Faso, and Mali are now willing to accept it. Compared to a few years ago, this is a stark difference – albeit not an entirely new phenomenon.

Burkina Faso, for example, has always had a relatively high willingness to accept a military takeover of power. This may have to do with rather benign experiences of military rule under Thomas Sankara in the 1980s and after the 2014 revolution. Sankara’s regime pursued a social-revolutionary agenda, expanding education and basic services. In 2015, the military was celebrated as it intervened against a short-lived coup d’état and secured a swift transition to democracy.

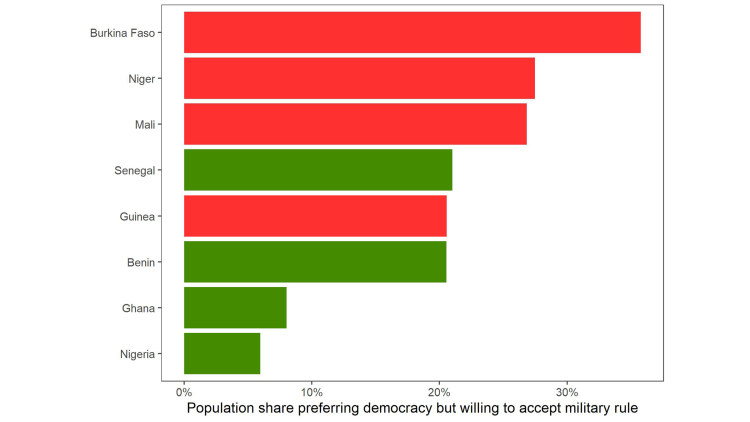

At the level of individual attitudes, there is considerable overlap between preferring democracy over any other regime type and being willing to accept military rule in times of crisis. In Burkina Faso, Niger, and Mali, this now appears to be the most prevalent sentiment. Democracy is still preferred, but military rule is simultaneously accepted (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Acceptance of Military Rule Coexists with Preferences for Democracy

Source: Author’s own elaboration, with population-weighted data from Afrobarometer Round 9 (2022/23).

Multiple factors contribute to the Sahel countries’ willingness to accept military rule. Among them, sheer desperation plays an important role. The pressure being exerted on the societies of the Sahel is immense: armed conflict with jihadist groups, escalating ethnic and intercommunal conflict, rapidly rising food and commodity prices, a lack of employment opportunities for a fast-growing population, the internal displacement of millions of people, restricted mobility, growing isolation, and a lack of market access all threaten future well-being, while making the status quo unbearable. Under these conditions, the military juntas’ promise to restore order by force, unrealistic as it may be given the scale and depth of the problems faced, is appealing to many. If alternative visions are lacking, citizens will clutch at any straw that gives them hope.

Populist rhetoric and militarism, meanwhile, have proven effective at deflecting the blame for the current crisis away from the security forces and projecting it onto civilian authorities and external actors – such as France, the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA), and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). Through narratives of sovereignty and liberation from neocolonial oppression, military juntas in Mali, Guinea, Burkina Faso, and Niger have been highly successful at capturing dissatisfaction in society and rallying public support. Propaganda and disinformation, actively fuelled by Russia, have caught on like wildfire throughout the region. Public discourse is contaminated by blurred facts, conspiracy ideologies and distorted perceptions of the success of military governments in neighbouring countries. The partnerships with Russia are framed as restoring sovereignty and independence in the fight against terrorism, namely by providing governments with the weapons they need to win the war and shake off the constraining influence of Europe and the UN – who are portrayed as duplicitous and clandestinely fuelling the conflict.

Finally, conflict aversion is a potentially important motivation for acquiescence towards the recent coups d’état. Given the fragility of state institutions and the escalation potential regarding social unrest, few people are willing to risk a high death toll in defence of civilian institutions. This is understandable considering how little political power the juntas wield on their own, and indeed how likely it is that they will remain in power only temporarily. In the immediate aftermath of a coup, juntas have an acute need for support from political and civil society actors and face extraordinary pressure from the international community. For junta leaders, there is no alternative to dialogue with internal and external powers. Negotiated transition roadmaps tend to reign in the worst consequences of a coup, leading to a minimum level of accountability and political inclusiveness. For those opposing the military takeover of power, the expectation that it will not immediately devolve into unfettered terror and kleptocracy can lower the perceived benefits of resistance.

Military Rule Has Little to Offer to Society

The factors that gave rise to the coups d’état and facilitated their acceptance in society are unlikely to contribute to their persistence in the long run. The main reason is that military governments are ill-positioned to address the problems of state-society relations that brought them to power in the first place.

The coup leaders’ legitimating promise was to restore order by force. This promise has proven difficult to keep, not only because the depth and complexity of the crisis but also because of the security forces’ continued dysfunction. The emerging power vacuum has paralysed state institutions. Western support has ended, and Russian mercenaries in Mali have earned notoriety for crimes against civilians – while also extracting lucrative resource deals from the Sahel. Jihadist groups have been successful at exploiting this situation, putting further pressure on the region’s states, and finding fertile ground for their propaganda among the victims of state-led violence. In Mali, the military junta evicted MINUSMA. Being unable to counter jihadist groups with Russian military assistance alone, the military government’s choices have given jihadists the opportunity to expand further in the country’s north. This has re-inflamed tensions with Tuareg armed groups, which controlled parts of northern Mali under the “Algiers Peace Accords” of 2015 (Africa Center for Strategic Studies 2023). The disintegration of the Malian state has accelerated. Thus, far from protecting society against insecurity, the coups d’état appear to have made things worse for the majority of the population.

Blame avoidance by military leaders appears to have been an important contributing factor to the coups d’état. Both in Mali and Burkina Faso, the coups happened at a time when public dissatisfaction with the deteriorating security situation grew to a point where it became inevitable to hold military leaders accountable. The Malian army in particular has a long history of systemic corruption (MacLachlan et al. 2015), perhaps so much so that it resembled more a criminal organisation than a state institution, lacking any type of meaningful civilian oversight. In Niger, it was Brigade General Abdourahamane Tchiani’s imminent replacement that triggered the coup, but his presidential guard was eventually joined by elements within the army that were eager to get back at President Mohamed Bazoum’s civilian government.

Tragically, the civilian presidents of Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger had long avoided security sector reform, possibly out of fear that it would trigger a military coup. In hindsight, their hesitation to address the dysfunctionality of the security sector may have made the coups inevitable, because incumbents failed to make any progress towards establishing civilian control over the military when they still had a fighting chance to do so. The evident lack of political resolve certainly did not help to increase to military leaders’ respect for civilian authority.

With civilians removed from power and international support withdrawn, the blame for a failure to stabilise the situation will fall on the military juntas alone. In other words, being a military dictator in the Sahel is not a very attractive proposition right now. As public discontent grows, the military juntas will face the choice between either relying more and more on repression, disinformation, populism, and their symbolic alliance with Russia, or advancing the transition agenda back to civilian government. Thus far, the Malian junta appears intent on staying in power indefinitely, while the Burkinabé government has worked in both directions simultaneously. The Nigerien junta is still struggling to find its position. In Chad, interim president Mahamat Idriss Déby Itno broke his initial promise of a transition to civilian government by October 2022, and appears intent on having his power reaffirmed through elections in 2024, a move that has been criticised by the opposition.

A Way Forward for Europe: Siding with Societies

As European governments are going through a phase of strategic reorientation in Africa and the Sahel, it will be important to learn from past mistakes. It will also be necessary to analyse dispassionately what Europe and the West actually have to offer in comparison to geopolitical rivals Russia and China. Since Europe as a whole is facing this question, governments should act collectively to find an answer.

In contrast to Russia and China, Europe’s history of colonial oppression and postcolonial interference in Africa is a massive liability. The weight of the colonialist past not only bears down on Franco–African relations, but to this day continues to profoundly affect how Africa is seen and thought of anywhere in Europe – and, of course, how Europe is seen in Africa. Europeans have yet to fully come to terms with the colonialist past. There might be no better opportunity than the current times of upheaval to confront that past and engage with African societies on different terms.

A first and necessary change for European foreign policy in the Sahel is to focus on societies instead of governments. For too long, European assistance to the Sahel has fallen victim to its own operating logic – namely, pursuing dialogue with governments, yet without adequately considering the broken feedback loop between governments and the societies they rule over. Rarely, if ever, did Western governments look behind the façade of formal institutions and evaluate whether political processes were actually reflective of societal preferences. Nor were data collected on public perceptions. Scant efforts were made to explain donors’ and diplomats’ assumptions to the public, and the few deliberate efforts in this regard, such as French President Emmanuel Macron’s 2017 speech at the University of Ouagadougou (Macron 2017), failed to strike a chord with the larger public.

While European policymakers’ endeavours to promote better governance and democracy in the Sahel were certainly sincere, they primarily relied on reform dialogue with government counterparts behind closed doors rather than in the public sphere. Civil society partners were integral to Europe’s governance and democracy support, but more often than not they were recruited from the thriving pool of donor-dependent organisations that specialised in catering to their patrons’ preferences. As a result, governance dialogue ended up being about what European policymakers believed African societies needed, rather than about fixing the broken feedback loop between African governments and their own societies.

The confrontational approach taken by the military governments in the Sahel has laid bare the ineffectiveness of such reform dialogue behind closed doors. Publicity-oriented actions such as the ban on all French non-governmental organisation activity in Mali and the expulsion of German Ambassador Dr. Gordon Kricke by the Chadian government suggest that the current rulers still have more to gain from dismantling their relations with Europe in public than from engaging in dialogue behind the scenes. Going forward, it will be in Europe’s best interest, then, to focus on rebuilding its public image and closing the feedback loop with the societies of the Sahel.

Siding with societies requires profound changes in how foreign policy, development assistance, and security policy are conceived, implemented, and promoted. First, this will require gathering data and monitoring sentiment regarding society at large. Compared to other world regions, the paucity of credible, scientifically informed data on public opinion in Africa is shocking.Afrobarometer is currently the only attempt made to monitor state–society relations over time, covering up to 39 countries of the continent every few years. With samples of just over 1,000 individuals per country, it is barely representative of the population as a whole and not fine-grained enough to identify diverging development trends across different localities or segments of society. Despite the widespread use of Afrobarometer’s data globally and the extraordinary value gained from it, the research network continues to struggle for funding. With relatively small investments in data and evidence, Europe could, as such, greatly improve its ability to understand the expectations and priorities of African societies as well as to act more in tandem with public sentiment across the continent.

Second, siding with societies requires full transparency towards the public in the Sahel countries about the assumptions and principles underlying Europe’s development, foreign, and security policy, allowing them to be critically evaluated by those directly impacted. It is not common for diplomats, military advisors, and development practitioners to reveal their own assumptions and knowledge gaps in public, for fear of criticism. Yet, public scrutiny is precisely the type of feedback European policymakers should invite in order regain credibility and prevent unintended consequences arising from their chosen courses of action. This is all the more important when recipient governments themselves are no longer accountable to society.

Third, siding with societies requires a willingness to give up on policy objectives or programmes that do not enjoy sufficient public support in the target society. This may be a bitter pill to swallow for policymakers who sincerely care about specific issues. However, in countries where most citizens no longer have a voice in politics, the perception of acting against a majority opinion – just because the government “bought in” to it – should be avoided at all costs. This will inevitably lead to greater humility in foreign and development policy. The experiences from involvement in Afghanistan and the Sahel have shown that not all of the West’s ambitions are realistic. Ensuring that policies and programmes have broad societal support in the target countries can be a way of preventing this type of overreach.

Fourth and finally, Europe should steer clear of any actions or attitudes that would undermine civil society’s capacity to fight for their own rights, freedom, and democracy when the time is right. Per their organisational logic, donors and diplomats have a preference for stable, untroubled working relationships with de facto governments. They also have a tendency to co-opt civil society organisations. To counteract these tendencies, European policymakers should proactively avoid complicity with the status quo and screen their actions for potential unintended consequences. Protecting spaces for home-grown civil society is crucial for the future of the Sahel countries. At some point, the military regimes will have exhausted their public backing. It is important to be prepared for that moment and not to stand in the way of African societies taking their future into their own hands.

Considering the inherent fragility of the military governments in the Sahel and their dependence on public support and acquiescence, Europe’s greatest potential source of influence is to act in sync with African societies. By their very nature, neither the military regimes nor Russia have much to offer to societies besides populism, disinformation, and repression. It is up to Europe and the West to fill this gap, namely by closing the feedback loop with African societies.

Until now, Europe’s collective performance in this respect has been disappointing. Widespread anti-French and anti-European sentiments are, in some ways, a logical consequence of that. The field of public diplomacy in the Sahel has been left almost entirely to Russia, which has perfected its influence through cynical manipulation strategies. The motives and assumptions underlying Europe’s and especially France’s engagement in the Sahel were never communicated in ways that appealed to broad societal majorities, nor were legitimate critiques raised by the public given the consideration they should have been given.

Yet, Europe’s failure to side with African societies in the past does not have to constrain their future relations. With greater efforts to genuinely listen to African societies, to come to terms with the colonial heritage, and to offer greater transparency about its objectives and assumptions, European foreign policy could strategically reposition itself for the time when the current de facto regimes come to an end. This is best done by focusing on what the current military regimes, Russia, and China routinely fail to offer: policies and actions that are broadly accountable to society.

Footnotes

References

Africa Center for Strategic Studies (2023), Mali Catastrophe Accelerating under Junta Rule, 10 July, accessed 27 November 2023.

Afrobarometer Data (2018–2023), Round 7–9, accessed 27 November 2023.

Craven-Matthews, Catriona, and Pierre Englebert (2018), A Potemkin State in the Sahel? The Empirical and the Fictional in Malian State Reconstruction, in: African Security, 11, 1, 1–31, accessed 27 November 2023.

Lierl, Malte (2021), Elections and Government Legitimacy in Fragile States, GIGA Focus Africa, 7, December, accessed 27 November 2023.

Lierl, Malte (2020), Growing State Fragility in the Sahel: Rethinking International Involvement, GIGA Focus Africa, 7, December, accessed 27 November 2023.

MacLachlan, Karolina, Elise Dufief, James Hall, Kari Kietzer, and Xavier Lhote (2015), Security Assistance, Corruption and Fragile Environments: Exploring the Case of Mali 2001–2012, London: Transparency International UK.

Macron, Emmanuel (2017), Emmanuel Macron’ s Speech at the University of Ouagadougou, 28 November, accessed 27 November 2023.

Editor GIGA Focus Africa

Editorial Department GIGA Focus Africa

Regional Institutes

Research Programmes

How to cite this article

Lierl, Malte (2023), Siding with Societies: How Europe Can Reposition Itself in the Sahel, GIGA Focus Africa, 5, Hamburg: German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), https://doi.org/10.57671/gfaf-23052

Imprint

The GIGA Focus is an Open Access publication and can be read on the Internet and downloaded free of charge at www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publications/giga-focus. According to the conditions of the Creative-Commons license Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0, this publication may be freely duplicated, circulated, and made accessible to the public. The particular conditions include the correct indication of the initial publication as GIGA Focus and no changes in or abbreviation of texts.

The German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) – Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien in Hamburg publishes the Focus series on Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and global issues. The GIGA Focus is edited and published by the GIGA. The views and opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the institute. Authors alone are responsible for the content of their articles. GIGA and the authors cannot be held liable for any errors and omissions, or for any consequences arising from the use of the information provided.