- Home

- Publications

- GIGA Focus

- Peaceful or Contentious? How to Promote Interreligious Peace in Africa

GIGA Focus Africa

Peaceful or Contentious? How to Promote Interreligious Peace in Africa

Number 2 | 2024 | ISSN: 1862-3603

Religion continues to play an important role in shaping cultures all over the world. In some societies religious diversity and coexistence are celebrated, while others grapple with (violent) religious extremism. What determines whether interreligious relations are peaceful or contentious? What can we learn from positive examples, and what role does religious extremism play in interreligious peace? Sub-Saharan Africa offers useful cases from which we can learn.

Levels of interreligious peace have been declining worldwide since 1990. Yet, this varies greatly across countries. Sub-Saharan Africa stands out as a region characterised by both very high and very low levels of interreligious peace from country to country.

Tolerant religious ideas, weak religious identification, favourable institutions governing religion, and a conducive socio-economic environment work in favour of interreligious peace.

In Sierra Leone and Togo, high levels of interreligious peace are maintained through cultures of peace engrained in close social bonds and lived religious tolerance. Challenges to interreligious peace are countered through peace advocacy efforts and supported by institutions designed to peacefully resolve conflicts and guarantee individuals’ freedom of religion or belief.

Violent religious extremism carries the risk of negatively affecting interreligious relations, as its divisiveness engenders the escalation of conflict, and it can lead to stigmatisation of members of certain religious or ethnic groups by association, the politicisation of religion, and forced displacement.

Policy Implications

Our analyses suggest that promoting close social ties and religious tolerance can contribute to developing a culture of interreligious peace. Potential negative effects of (violent) religious extremism on interreligious peace may be avoided by strengthening legal frameworks and law enforcement, addressing socio-economic disparities, and engaging with religious leaders and civil society.

Interreligious Conflict or Peace: Why It Matters

The relevance of religion worldwide continues to grow: 84 per cent of the world population identified with a religion in 2010, and this number is expected to increase to 87 per cent by 2050. It will particularly be driven by increases in both population size and proportions of believers on the African continent (Pew Research Center 2015).

Religion can be both a source of conflict and a source of peace. On the one hand, many conflicts have religious connotations or components, such as the Sudanese wars that led to the independence of South Sudan, or attacks by violent groups with extremist religious ideologies, such as al-Jamaʿat Nusrat al-Islam wa-l-Muslimin (better known as Boko Haram) and the so-called Islamic State (IS) in Burkina Faso. On the other hand, religion can be a source of morality, and religious ideas are often used to propagate peace and cooperation. For example, religious leaders often call for peace and help prevent the spread of extremist ideologies in their local congregations.

Conflicts are typically multifaceted. They usually involve non-religious dimensions, such as ethnicity, politics, or economics. Still, even if religion is not at the root of a conflict, it can be used as a tool to mobilise conflicts, along with making conflicts more intense (“bloodier”) and longer (Deitch 2022).

Global Trends: Declining Interreligious Peace, but High Variability across Regions

Globally, researchers are observing an increase in religious violence: In fact, the share of active conflict dyads engaged in violent conflict over a religious issue has risen dramatically over the last several decades. This holds true for Africa in particular. In 2022, out of 26 active state-based armed conflicts in Africa, 17 included groups with extremist religious ideologies (Davies, Pettersson, and Öberg 2023), mostly affiliates of IS and al-Qaida.

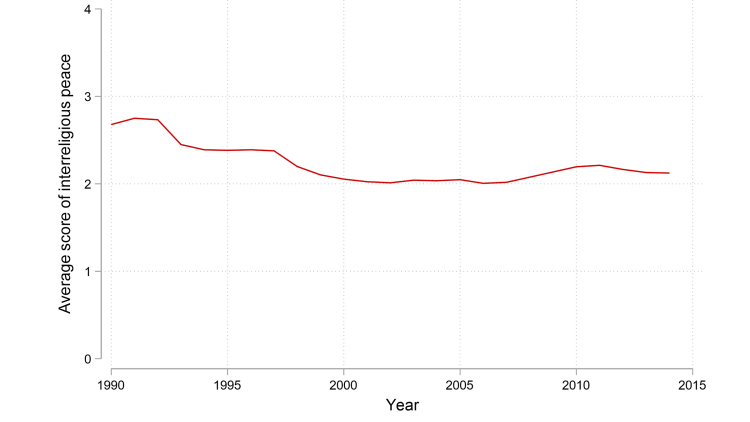

While many analyses focus on religious violence, we investigate interreligious peace, since we understand peace as more than the sheer absence of physical violence. We understand interreligious peace as the absence of physical violence, hostile attitudes, and mutually perceived threats in interreligious relations, as well as the presence of interreligious cooperation and trust. By using an existing database (Vüllers, Pfeiffer, and Basedau 2015), we developed an interreligious peace index for the years 1990 to 2014, covering most countries worldwide (see Figure 1 below). The highest level of interreligious peace is “4” while the lowest level is “0.” We found that interreligious peace was lower in 2014 than in 1990.

Figure 1. Global Average Level of Interreligious Peace, 1990–2014

Source: Authors’ own illustration.

However, the developments differ greatly by world region and by country. Figure 2 shows the level of interreligious peace in the year 2014. Darker shades of blue indicate higher levels of interreligious peace, while lower shades of blue indicate lower levels thereof. Zooming in on sub-Saharan Africa, there is a lot of heterogeneity in the region, with some countries showing very high levels of interreligious peace (e.g. Ghana, Sierra Leone, and Togo) while other countries, such as Nigeria and Sudan, display particularly low levels. Given the dynamics of active conflict dyads involving religious violence, interreligious peace in some countries (e.g. Burkina Faso, Mozambique) is lower now than in 2014.

These findings are in line with those of surveys such as the Afrobarometer, which have measured the willingness of African populations to live with neighbours of a different religion. The proportion of individuals who dislike or strongly dislike living with neighbours of a different religion has consistently ranged between 11 per cent and 12 per cent of the surveyed population, with an increase to 14 per cent in the last round in 2022. However, these figures can obscure significant disparities between African regions. Religious intolerance is notably more pronounced in North African countries (36 per cent) than in sub-Saharan African regions (7 to 14 per cent).

Figure 2. Interreligious Peace in 2014

Source: Authors’ own illustration.

Note: The darker the colour, the more peaceful the country.

What Explains Interreligious Conflict or Peace?

In view of declining interreligious peace and the myriad of differences across countries, it is important to examine the main drivers of interreligious peace (see also literature review in Köbrich and Hoffmann 2023). There are factors specific to religion, such as religious ideas, religious identities, religious practices, and institutions governing religion, as well as non-religious factors that help explain both interreligious conflict and interreligious peace.

Religious ideasgive theological justifications to specific behaviours and can thereby also prescribe how people should act. The content of religious ideas determines the type of behaviour. For example, calls for violence by religious elites can lead to religious violence (Basedau, Pfeiffer, and Vüllers 2016) and the idea that one’s own religion is the only “one true religion” can lead to discrimination, hostile attitudes, and distrust vis-à-vis “non-believers.” On the contrary, ideas such as believing that your religion requires loving all human beings can lead to more equal treatment of members of other religious groups (Hoffmann et al. 2020). Although religious leaders use their religion’s resources to call for peace, such calls seem too little, too late.

Religious identity describes a person’s (self-ascribed) belonging to a religious group. If religious identities are important in a given situation, people tend to favour members of their own group over members of other groups. Especially when the “other” is perceived as threatening or when people believe in very exclusive religious ideas, strong identification with one’s religious group tends to counteract interreligious peace. If religious differences are reinforced by ethnic, regional, or other differences, the conflict risk increases. However, positive contact between believers of different faiths can mitigate this bias (Kanas, Scheepers, and Sterkens 2017).

Institutions governing religion matter for interreligious peace: If power is shared between members of different religions, and people are subsequently treated equally, interreligious peace becomes more likely. By contrast, when people feel treated unfairly by the government because of their religious affiliation and when they perceive others as threatening, they are more likely to support violence. The existence and strength of transnational ties can intensify interreligious conflict.

Finally, non-religious factorsmatter for interreligious peace. For example, socio-economic marginalisation is one of the drivers of recruitment to violent groups, and theories suggest that particularly youths who are excluded from economic opportunities are prone to be pulled into violence. Education has been found to be a source of resilience against violence, possibly as it enhances critical thinking and respect for diversity (UNDP 2023).

Thus, a variety of factors, both religious and non-religious, explains interreligious violence and peace. Often research and policy reports focus on violence and barriers to peace – but what can be learned from positive examples?

Positive Examples: Sierra Leone and Togo

There are some countries where interreligious relations are more peaceful than in others, as Figure 2 shows. Togo and Sierra Leone are two such cases. Qualitative interviews that we conducted in both contexts offer local perspectives on why interreligious relations are rather peaceful.

Sierra Leone presents itself as a particularly outstanding case of peaceful interreligious relations. While there has been some instability recently, this is not related to religion. Additionally, the country does not have a history of religious violence; in fact, relations between religious communities have generally been characterised by respect and collaboration. According to the latest data from Afrobarometer collected in 2022, large sections of society trust members of other religions (65 per cent), and few people dislike having neighbours who follow a different religion (8 per cent). Members of the two main religious communities – Muslims (77 per cent) and Christians (22 per cent) – live side by side in the same neighbourhoods and even within the same families. The survey we conducted in Freetown at the end of 2022 suggests that many Muslims and Christians have friends of both religions (83 per cent) – and 17 per cent of the married respondents are married to someone of a different religion. On an organisational level, Christian and Muslim communities collaborate closely within the Interreligious Council of Sierra Leone, which has been bringing together leaders of various denominations since 1997. Given this record, some of our qualitative interview partners were convinced that Sierra Leone would prove the most religiously tolerant country in the world.

Interreligious relations in Togo have also been largely peaceful, but the existing interreligious peace seems more fragile, especially in times of a rising threat of violent religious extremism. After an attack on security forces in Northern Togo in November 2021 by violent religious extremist groups entering the country from Burkina Faso, reports of violence have become increasingly common (Weiss 2022). To what extent these attacks are supported by the Togolese people is unclear, as is how the rise of violent religious extremism may be impacting interreligious relations in society at large. We discuss potential impacts of violent religious extremism on interreligious relations in the next section. Afrobarometer data from the last round collected in 2022 offers evidence that Togo has maintained its high level of interreligious peace for now. As in Sierra Leone, only few respondents reported not liking having neighbours who follow a different religion (5 per cent), and the majority trust members of another religion somewhat or a lot (65 per cent). The survey we conducted in Lomé indicates that Muslims and Christians mix: 88 per cent of respondents had friends from both communities, and the rate of interreligious marriages was 10 per cent. Religious leaders and organisations collaborate in various ad hoc and local groups but have not formalised a permanent national interreligious institution.

When highlighting Togo and Sierra Leone as good examples of interreligious peace, we focus on Christian–Muslim relations. However, relations between so-called imported religions – Christianity and Islam – and indigenous African Traditional Religions (ATR) seem more complicated. On the one hand, ATR are considered the heritage or an aspect of common origin among all Togolese or Sierra Leoneans and, as such, command respect. ATR are also a resource people turn to in times of crisis, such as illness or personal hardship, even if they identify as Christians or Muslims. On the other hand, we heard of people hiding their practice of ATR due to prejudices that juxtapose their religion with “modernity” and raise suspicions that they could use (their) spiritual powers to harm others. That said, how are Sierra Leone and Togo able to uphold this relative level of interreligious peace?

Culture of Peace: It Works “Automatically”

Our interviewees identified culture as key to what helps Togo and Sierra Leone maintain high levels of interreligious peace – culture in the sense of social and behavioural norms vis-à-vis members of other religions. Interreligious peace appears effortless and without alternative when interviewees explain that they simply act in accordance with examples set by previous generations. For instance, a Sierra Leonean interviewee working for a human rights organisation said,

We met that oneness among them, that cohesion among them, so that is what we also are practising, you know, it’s a culture now. So, we are practising it.

In other interviews, culture is not mentioned explicitly but is reflected in statements that make interreligious peace appear self-evident. As a Togolese imam, for example, described,

I do not have any idea why we do not have problems in Togo […] I only see that it works automatically.”

Although seeming normal and effortless, the existing culture of peace must be maintained. One way to do this is to act in line with the culture of peace – even if it is purely out of routine or habit.

Close Social Bonds and Religious Tolerance

Close social bonds and religious tolerance, for example, seem central to the culture of interreligious peace and were common explanations for interreligious peace in our interviews. It is common for Sierra Leoneans and Togolese to occupy religiously diverse spaces, which makes it normal and acceptable to them to interact with members of other religions. Indeed, our research has shown that perceiving interreligious interactions to be common and acceptable was positively associated with individuals’ own positive contact experiences (Köbrich, Martinović, and Stark 2023). In this way, their own bonds with people of other religions keep the culture of interreligious peace alive. Close social bonds are also cited as a source of resilience because they are viewed as making interreligious violence improbable. After all, why should anyone turn against the people they love, their parents, their children, their friends? Religious tolerance, the conviction that everyone is free to follow the religion of their choice, is another important aspect of the culture of interreligious peace in Sierra Leone and Togo. A Sierra Leonean interviewee told us,

I don’t see any reason why we should be having problems. That’s about our faith. They have their own faith, and that’s their right, it’s a human right.

Living up to the value of religious tolerance in word and deed maintains the culture of interreligious peace by normalising respectful treatment of people of other religions.

Facing Challenges: Advocacy and Institutions for Interreligious Peace

Cultures of interreligious peace in Sierra Leone and Togo are by no means utopic. In our quantitative survey, for instance, 24 per cent of Togolese and 11 per cent of Sierra Leoneans do not think that it is acceptable for a Muslim man to marry a Christian woman. Similarly, incidents of conflict regularly featured in the interviews, such as noise emanating from places of worship creating tensions in neighbourhoods in both countries. Given existing challenges, (inter)religious organisations and leaders, state authorities, and civil society actors have been making efforts to preserve interreligious peace in Sierra Leone and Togo. Our interviewees often highlighted that religions in their country stand for peace, and that religious leaders preach ideas supportive of interreligious peace, such as the principle of loving one’s neighbour. The assumption here is that advocacy by religious institutions and leaders shapes cultures of interreligious peace by changing the minds of those challenging interreligious peace and serving as role models for their followers. As one interviewee claimed,

You are going to realise that what happens at the top can also be seen at the bottom, at the level of the followers.

In the same vein, activities by the Interreligious Council of Sierra Leone and efforts by the Togolese government and civil society actors that bring together various religious stakeholders may be important beyond the issues discussed during the meetings, as they demonstrate lived collaboration between religions.

In the face of challenges, institutions can further sponsor interreligious peace through efforts of conflict resolution and by guaranteeing the freedom of religion or belief. These efforts are particularly important because they can preclude the escalation of conflicts. In Togo, the government was lauded by several interviewees for its impartiality towards religious groups, thereby living up to the constitutionally prescribed principle of laïcité andgiving weight to religious tolerance and the free choice of religion. It also allows the Direction des Cultes (a ministerial authority) to mediate conflicts in interreligious relations, such as problems of noise, if religious communities cannot reach an understanding with their neighbours. In Sierra Leone, interviewees suggest that the Interreligious Council would be called upon in times of crisis – not only concerning interreligious peace but any issue inhibiting peace and social cohesion in Sierra Leone. The council’s authority stems from its involvement in the resolution of the Sierra Leonean Civil War and its representation of both Muslims and Christians, which enable it to act as conflict mediator and guarantor of (interreligious) peace in Sierra Leone. These and other institutions are key because they guarantee freedom of religion or belief and are there to resolve issues wherever they may arise. As a traditional chief from Sierra Leone confidently claimed, “Problem will come, but we solve it.”

The Rise of Violent Religious Extremism Could Endanger Interreligious Relations

The emergence of violent Islamism in sub-Saharan Africa began in the Horn of Africa, most notably in Somalia. It subsequently expanded westward, affecting Kenya, Uganda, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, among others. In West Africa, a second focal point emerged with the rise of Boko Haram in Nigeria in 2009, which later spread to the Lake Chad Basin, encompassing Chad, Cameroon, and Niger. The Sahel region in West Africa has become a new epicentre of religious extremist movements since the downfall of Muammar Qaddafi in 2011. Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, Côte d’Ivoire, Togo, and Benin have also suffered under this influence (see also Basedau 2022). The most recent hot spot is Southern Africa, specifically Mozambique, where Islamist insurgents are targeting both economic infrastructure and Christian communities. It is worth noting that Islamist violence often affects Muslims more than non-Muslims. However, the rise in religious extremism, if not adequately managed, could also give rise to interreligious divisions in several ways:

Divisiveness

Extremist groups often manipulate religious or ethnic differences to further their agendas, promoting sectarian or exclusivist interpretations of religion and fostering divisions among various religious communities. Frequently, these extremist groups intentionally take aim at religious sites and monuments, many of which hold great significance for multiple religious communities. The destruction of these sites can provoke profound offence and exacerbate divisions. An illustrative incident occurred in Mali in 2012 when Ansar Dine insurgents demolished seven out of the 16 mausoleums of revered Muslim saints and vandalised the entrance of a mosque within a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Not only was the local population deeply displeased, but the actions also garnered nearly unanimous condemnation from the international community. In the end, such outrageous attacks by extremists harden the fronts, accelerate escalation, and raise the risk of stigmatisation.

Stigmatisation

Extremist acts committed by individuals or groups claiming to represent a particular faith can lead to stigmatisation of the entire religious or ethnic community (the latter of relevance when religious differences are reinforced by ethnic differences). This can strain relations with other religious groups and foster mistrust. In the Sahel, certain Islamist groups in leadership positions are of Fulani descent. Tragically, when insurgents target other communities, there are instances where these groups retaliate by attacking neighbouring Fulani communities, alleging their collusion with the jihadists. This disturbing cycle has led to numerous reported massacres in Burkina Faso and Mali, as documented by human rights organisations.

Politicisation of Religion

Extremist movements often aim to gain political power or influence through religious narratives. This politicises religious identities and can result in conflicts over the role of religion in governance, further complicating interreligious relations. In Nigeria, for instance, in a bid to secure voter support, politicians have enforced shariʿa law in 12 northern states. While these states have a Muslim majority, they also host significant religious-minority communities. Unfortunately, this religious imposition has given rise to tensions, as non-Muslim communities are compelled to adhere to shariʿa regulations or leave their homes.

Forced Displacement

Extremist violence can lead to the displacement of religious minorities, as they flee from areas where members of their faith are in the minority. In Northern Nigeria, Islamist insurgents, notably Islamic State’s West Africa Province (ISWAP), frequently target Christians and their places of worship, resulting in the forced displacement of Christian communities from areas under the insurgents’ control. This displacement can disrupt established interreligious communities and relationships.

It is important to note that many African countries have a long history of interreligious coexistence and cooperation, and these relationships remain resilient in the face of extremist threats. Nonetheless, ongoing efforts are needed to maintain and strengthen interreligious peace in the face of these challenges.

The Making of Interreligious Peace

Addressing the challenges posed by the rise of violent religious extremism and preserving interreligious peace in Africa requires a comprehensive set of policy recommendations. Here are four of the most important:

Promoting close social ties and tolerance is key.This can be done by creating spaces and encouraging interfaith encounters that bring religious leaders and communities from different faiths together to foster understanding, cooperation, and tolerance. Moreover, educational programmes that promote religious literacy and respect for diversity should be supported. Young people should learn about different religions and the importance of coexistence, with a focus on tolerant religious ideas.

Legal frameworks and law enforcement must be strengthened.Legal mechanisms to combat hate speech, incitement to violence, and extremism should be enhanced to ensure that they are effectively enforced and that individuals and groups promoting extremism are held accountable. Freedom of religion or belief needs to be promoted, and a legal environment should be fostered that ensures equal treatment of all. Rules and regulations need not become stricter; rather, it is important that they are ensured. However, consideration should be given to the potential problem of using the security apparatus to counter hate speech and extremism or to guarantee freedom of religion or belief, as it can have adverse consequences.

It is crucial toaddress socio-economic disparities. Policies and programmes that address socio-economic disparities should be implemented, as these disparities can aid extremist recruitment. This includes efforts to reduce poverty, improve access to education and job opportunities, and reduce economic inequalities. Economic empowerment and inclusion of marginalised communities need to be promoted as counterweights to extremist narratives that exploit grievances.

Engaging with religious leaders and civil society is important. Collaborations with religious leaders to counter extremist narratives within their communities can be promising. Messages of peace, tolerance, and social cohesion should be promoted. Civil society organisations that work to counter extremism and promote interreligious peace should be supported, providing resources and platforms for their efforts.

These recommendations emphasise the importance of a multifaceted approach that combines legal, social, and educational measures to address religious extremism and foster interreligious relations based on tolerance, cooperation, and respect. Collaboration between governments, religious institutions, civil society, and international partners is crucial to implementing these policies effectively.

Footnotes

References

Basedau, Matthias (2022), „The Bigger Picture“: Mali, Dschihadismus und der Rückzug des Westens, GIGA Focus Afrika, 3, April, accessed 26 February 2024.

Basedau, Matthias, Birte Pfeiffer, and Johannes Vüllers (2016), Bad Religion? Religion, Collective Action, and the Onset of Armed Conflict in Developing Countries, in: Journal of Conflict Resolution, 60, 2, 226–255, accessed 26 February 2024.

Davies, Shawn, Therése Pettersson, and Magnus Öberg (2023), Organized Violence 1989–2022, and the Return of Conflict between States, in: Journal of Peace Research, 60, 4, 691–708, accessed 26 February 2024.

Deitch, Mora (2022), Is Religion a Barrier to Peace? Religious Influence on Violent Intrastate Conflict Termination, in: Terrorism and Political Violence, 34, 7, 1454–1470, accessed 26 February 2024.

Hoffmann, Lisa, Matthias Basedau, Simone Gobien, and Sebastian Prediger (2020), Universal Love or One True Religion? Experimental Evidence of the Ambivalent Effect of Religious Ideas on Altruism and Discrimination, in: American Journal of Political Science, 64, 3, 603–620, accessed 26 February 2024.

Kanas, Agnieszka, Peer Scheepers, and Carl Sterkens (2017), Positive and Negative Contact and Attitudes towards the Religious Out-Group: Testing the Contact Hypothesis in Conflict and Non-Conflict Regions of Indonesia and the Philippines, in: Social Science Research, 63, March, 95–110, accessed 26 February 2024.

Köbrich, Julia, and Lisa Hoffmann (2023), What Do We Know about Religion and Interreligious Peace? A Review of the Quantitative Literature, in: Politics and Religion, September, 1–25, accessed 26 February 2024.

Köbrich, Julia, Borja Martinović, and Tobias H. Stark (2023), Interreligious Contact and Attitudes in Togo and Sierra Leone: The Role of Ingroup Norms and Individual Preferences, in: Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, November, accessed 26 February 2024.

Pew Research Center (2015), The Future of World Religions: Population Growth Projections, 2010-2050, 2 April, accessed 26 February 2024.

UNDP (2023), Journey to Extremism in Africa: Pathways to Recruitment and Disengagement | United Nations Development Programme, 7 February, accessed 26 February 2024.

Vüllers, Johannes, Birte Pfeiffer, and Matthias Basedau (2015), Measuring the Ambivalence of Religion: Introducing the Religion and Conflict in Developing Countries (RCDC) Dataset, in: International Interactions, 41, 5, 857–881, accessed 26 February 2024.

Weiss, Caleb (2022), JNIM Claims Deadly Assault in Northeastern Togo, FDD’s Long War Journal (blog), 30 November, accessed 26 February 2024.

Editor GIGA Focus Africa

Editorial Department GIGA Focus Africa

Research Project

Regional Institutes

Research Programmes

How to cite this article

Akinocho, Hervé, Lisa Hoffmann, and Julia Köbrich (2024), Peaceful or Contentious? How to Promote Interreligious Peace in Africa, GIGA Focus Africa, 2, Hamburg: German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), https://doi.org/10.57671/gfaf-24022

Imprint

The GIGA Focus is an Open Access publication and can be read on the Internet and downloaded free of charge at www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publications/giga-focus. According to the conditions of the Creative-Commons license Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0, this publication may be freely duplicated, circulated, and made accessible to the public. The particular conditions include the correct indication of the initial publication as GIGA Focus and no changes in or abbreviation of texts.

The German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) – Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien in Hamburg publishes the Focus series on Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and global issues. The GIGA Focus is edited and published by the GIGA. The views and opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the institute. Authors alone are responsible for the content of their articles. GIGA and the authors cannot be held liable for any errors and omissions, or for any consequences arising from the use of the information provided.