- Home

- Publications

- GIGA Focus

- Latin America: Germany’s Indispensable Partner

GIGA Focus Latin America

Latin America: Germany’s Indispensable Partner

Number 2 | 2025 | ISSN: 1862-3573

With the US turning to bully politics and tariffs, Latin America can become a more important partner than ever for Germany. As the Trump administration dismantles the soft-power structures the US had built over decades, Latin American countries have reason to seek cooperation with Europe. With smart policy, the new government in Berlin can leverage shared interests, economically as well as politically.

Political divisions afflict Latin America’s regional organisations. Where region-to-region accords do not materialise, Germany should seek cooperation with individual countries and “coalitions of the willing.”

After decades of EU–Mercosur negotiations, Germany needs to push for reluctant EU member states to sign the finalised agreement.

The special fund for infrastructure investment gives Germany a chance to promote green energy cooperation with Latin America in win–win models for both sides.

Germany has a comparative advantage when it combines industrial investment with skills and knowledge transfer.

Drug trafficking erodes the rule of law in both Latin America and Europe. Responses should be smarter, not harder. This requires increased cooperation between European and Latin American partners, by building on promising initiatives such as strategic alliances between port cities.

As Trump rages against US academic and cultural institutions, Germany’s long-standing cultural and scientific exchange formats shine all the brighter. Investing in these will be a low-cost but key asset for a renewed social, political, and economic partnership.

Policy Implications

Germany and the EU will need to maintain their commitment to civil liberties and democratic standards, even if the US is no longer an ally in this cause. Human rights defenders should be supported. Also, Latin American businesses have as much of a vested interest in the effective rule of law as German investors and trade partners do.

“Zeitenwende 2.0”: Foreign Policy in Times of Trump

When Russia invaded Ukraine, German chancellor Olaf Scholz spoke of a “Zeitenwende” (“dawn of a new era”), calling for a fundamental rethinking of European politics. Donald Trump’s re-election as US president marks a second “Zeitenwende,” upending the world that had hitherto shaped our thinking and our institutions even more fundamentally. As German and European policymakers navigate the tumult, Latin America will be an indispensable partner.

Except for Canada, Latin America and the Caribbean is the world region most closely intertwined with the US. If much of Trump’s foreign policy can be understood as “weaponising asymmetric interdependence” – to put a spin on a term introduced by Drezner, Farrell, and Newman (2021) – Latin America and Europe are both finding themselves on the receiving end of it. Trump’s disruptive policies can inadvertently provide the impetus to bring Europe and Latin America closer together. With smart policies, the incoming German government can leverage shared interests for a renewed partnership.

The Divided States of the Americas

The new US administration is confronting all Latin American countries with similar challenges, such as punitive tariffs, the deportation of immigrants, and criticism of China’s influence. One might have expected this to strengthen regional cooperation as a means of taking common positions and showing solidarity. However, so far, the opposite has been the case. After the US announced the mass deportation of Latin American migrants, the president of the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) convened a hybrid emergency summit for 30 January 2025 but was forced to cancel it because too few heads of state were willing to participate. In April, Honduran president Xiomara Castro will hand over the CELAC pro tempore presidency to her Colombian counterpart, Gustavo Petro. Little indicates that he will be able to unite Latin American and Caribbean countries more than his predecessor.

Most Latin American governments, including the two regional heavyweights, Mexico and Brazil, are trying to find their own modus vivendi with the US government, hoping to thus minimise the costs to themselves. Argentina, El Salvador, and Paraguay, on the other hand, see themselves as allies of the Trump administration and are trying to avoid negative impacts by showcasing particularly close cooperation.

This is happening at a time when Latin American regionalism is in crisis. The Javier Milei government in Argentina has been calling into question the usefulness of the Southern Common Market (Mercosur), a trade bloc amongst the countries of South America’s Southern Cone plus Brazil. The Union of South American Nations (UNASUR) remains a zombie entity, as calls for its revitalisation have not progressed beyond formal announcements. Latin American governments are too ideologically divided. The three openly authoritarian elephants in the room – Cuba, Nicaragua, and Venezuela – make regional cooperation even more difficult to achieve.

However, the election on 10 March of Surinamese foreign minister Albert Ramdin as the new secretary-general of the Organization of American States (OAS) showed how skilful diplomacy gives Latin American and Caribbean countries considerable agency. His opponent, Paraguay’s foreign minister Rubén Ramírez, is ideologically much closer to Trump. However, Ramírez eventually dropped out of the race when it became evident that not only the Caribbean states but also the left-wing presidents of Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, and Uruguay would be united in their support of Ramdin’s candidacy. The Surinamese foreign minister is an experienced career diplomat who served as OAS assistant secretary-general for two terms. He now faces the formidable tasks of mediating between the different positions of Latin American governments and meeting the critical eye of the US government, which can withdraw its financial support (accounting for 60 per cent of the OAS budget) at any time.

Can Europe Set an Example on Trade Liberalisation?

In terms of trade and investment, Latin America offers Germany – and the EU – a unique opportunity to establish itself as a viable alternative to the US–China dichotomy. Trump’s looming electoral victory, among other factors, may have provided the final push for the successful conclusion of the EU–Mercosur agreement in December 2024. However, that agreement still must be signed and ratified. The new German coalition government (CDU/CSU/SPD 2025) explicitly lists this as a priority task – without, of course, detailing how the reluctance of some EU member states to do that will be overcome.

In the revised agreement (and its annexes), the EU has been very accommodating to some of Mercosur’s demands – Brazil’s in particular. It also commits the EU and Mercosur to the Paris Agreement on climate change, from which the US has once again withdrawn under Trump. The EU’s swift ratification of its agreement with Mercosur would signal Europe’s commitment to free trade and to operating a partnership of equals, which could be a powerful catalyst for further cooperation given both sides have a stake in stable and strong multilateral institutions.

The EU–Mercosur Agreement is not the only agreement that the EU is negotiating with Latin America. The modernised EU–Chile Interim Trade Agreement entered into force in February 2025, and negotiations on the modernisation of the EU’s Global Agreement with Mexico concluded in January 2025, though it still needs to be signed and ratified. This shows that the EU continues to be an important, though sometimes overlooked player in Latin America, especially when it comes to investments by European companies. Moreover, the agreements have always included political dialogue with the EU’s Latin American partners.

The upcoming fourth EU–CELAC summit planned for November 2025 in Colombia provides a chance to further advance a shared political agenda. However, against the backdrop of Latin America’s continued discord, expectations should be tempered. Where region-to-region agreements seem unlikely, the EU should focus on cooperation with subregional organisations, individual countries, or with like-minded governments in “coalitions of the willing.”

Energy Cooperation and Climate Policy

The potential for economic complementarity between Latin America and Europe is particularly evident in the energy sector: some 60 per cent of Latin America’s electricity generation comes from renewable sources, with significant room for expansion remaining. To fulfil this potential, however, a large financial gap needs to be bridged, as a recent OECD (2024) report indicates. To that end, the new EUR 500 billion special fund for infrastructure, approved by the outgoing Bundestag, provides an opportunity to spur green energy projects with partners in Latin America. As many economies in the region struggle to sustain longer periods of economic growth, partnering with Europe becomes of particular appeal.

This synergy is especially evident in the case of the climate agenda. At a time when Germany recognises the need to both boost investment (especially related to infrastructure and climate) and re-orient its development-cooperation policy, this is particularly fitting. Projects related to wind and solar power as well as green hydrogen are obvious examples. Germany, jointly with the EU, has the means as well as the necessary capacity to foster green infrastructure in Latin America. This would be a win–win situation not only in economic terms but also in that it would position the EU as a credible alternative to China in the region.

The continent’s largest economy, Brazil, was in the past a key partner for German overseas investment, Germany having been a crucial contributor to Brazil’s industrial development starting in the 1960s. Although this partnership has lost some steam in recent decades, the conditions are ripe for it its reinvigoration. Brazil’s “New Industrial Policy” and “Ecological Transformation Plan” (Ministério da Fazenda 2024) focus on technology development for the energy transition and aim to attract investments and resources that, in many cases, German companies could deliver, from the car industry to offshore wind production. As in the past with the automotive industry, Germany has a comparative advantage when investment is combined with skills and knowledge transfer. Such an economic partnership could find its political complement in shared climate change commitments and goals. The UN Climate Change Conference “COP30,” which will meet in Belém, Brazil, in November of this year, presents a unique opportunity for Germany and Brazil – or more widely, Europe and Latin America – to show unity in the face of the US’s withdrawal from the Paris Agreement.

Supporting the Rule of Law

Like other world regions, Latin America is currently experiencing an erosion of democratic rights, civil liberties, and the rule of law. Those voted into the presidency are undermining the functioning of democratic institutions, the independence of the judiciary, and the sanctity of electoral authorities. A case in point is El Salvador, as President Nayib Bukele’s repressive security policies are widely celebrated across the region and beyond, despite their systematic violation of core democratic and judicial norms such as the right to due process. While public security is a key concern of citizens across Latin America that certainly needs to be addressed, Germany should make clear that this cannot be a pretext for abandoning democratic norms that were achieved at high cost after decades of military dictatorships and – in the Central American case – civil wars.

While authoritarians’ “iron fist” policies may be popular in the short term, all forms of direct physical violence must be comprehensively addressed to safeguard public security in the longer run. The experiences of German Prevention Day (Deutscher Präventionstag) could serve as an interesting model in this context. Additionally, Germany’s development-cooperation agencies and its “parteinahe Stiftungen” – the political foundations linked to each of Germany’s parties – have an important role to play. Ultimately, it is crucial to promote and connect the many positive local initiatives to maximise their impact and contribute to broader change.

Germany has long fostered dialogue on the rule of law with international partners, the so-called “Rechtsstaatsdialog.” As this in the past included non-democratic countries such as China and Vietnam, it also has the capacity to be a vital instrument in Germany’s current cooperation with Latin American partners, from high-performing democracies to authoritarian governments and everything in between. Moreover, German and local businesses have a vested interest in maintaining a basic level of legal certainty and rule of law, as it provides them with stability and predictability.

An example of political interference with courts is the recent judicial reform in Mexico that introduced popular elections for judges at all levels. The reform aimed to solve various judicial deficiencies, given the high levels of corruption and impunity. However, it also threatens to curtail the independence – and quality – of Mexico’s judicial system, as the proposed rules for the pre-selection of candidates and for the elections might open the door to increased government influence over the courts. Moreover, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (2024) expressed its concern that organised crime may influence electoral outcomes, at least in some Mexican states. As judicial elections will be held on 1 June 2025, external actors should ally with domestic organisations that monitor the pre-selection, campaigning, and election process in order to keep them free from undue political interference.

External support should also foster institutional dialogue between courts and society, facilitating the improvement of oversight mechanisms on institutional transparency. If implemented, a higher degree of societal participation in judicial decision-making and the monitoring of compliance with court rulings would increase judicial effectiveness, having a positive impact on trust in courts. Similarly, transparency has been found to increase public confidence in institutions. In the case of a government attack on its independence, a well-respected court is more likely to be defended by society and domestic stakeholders.

Standing unequivocally with the rule of law is imperative in the case of Brazil, where the Supreme Court ruled that former president Jair Bolsonaro and seven close allies, including former defence ministers and security officials, will stand trial for allegedly plotting a military coup to stay in power after losing the 2022 election. On a continent that has suffered from military dictatorships in the past, this assertion of civilian authority over coup-plotters is a milestone for democratic governance. If convicted, Bolsonaro faces over 40 years in prison.

However, the trial is set to become highly politicised, with Bolsonaro rallying his base and seeking support from international allies. With Trump leading a frontal attack against “radical-left judges,” the Bolsonaro trial may well become a prominent cause for the international far right. Even if the US is no longer an ally in this cause, Germany and the EU need to be unwavering in both their commitment to the rule of law and the support of the actors who help sustain or fight for these values on the ground in Brazil.

Drug Trafficking – Shared Responsibility, Shared Responses

Drug trafficking intimately links Latin American producers with European consumers. It can be tackled only as a shared responsibility. Despite efforts to interdict shipments, eradicate cultivation, and arrest drug traffickers, Europe’s demand for cocaine has continued to surge. Prices have gone down as the available supply from the Andean region has increased. These trends only exacerbate the acute challenges posed by transatlantic drug trafficking, as attested to by record seizures of cocaine shipments in European ports.

The drug economy is not only immensely lucrative but also destructive, as it contributes to corruption, the deterioration of the rule of law, and the empowerment of illegal (and often violent) non-state actors. This is not playing out only in Latin America: increased incidents of narcotics-related violence have been causing alarm across Europe, too. Corruption schemes involving law-enforcement officials as well as sophisticated money-laundering operations using cryptocurrencies have been uncovered in Germany in recent years.

Despite these challenges, key lessons from the “war on drugs” the US has promoted in Latin America for decades should not be forgotten. Confrontational counter-narcotics operations can fuel extraordinary levels of violence. Militarised hardline approaches can be popular, but they do little to change underlying incentive structures. Fighting drug production and drug trafficking requires a scalpel, not a bazooka. The new German government should endeavour to fight Latin American drug production and transatlantic trafficking smarter, not just harder.

Go-it-alone strategies tend to relocate the problem rather than solve it. As the Port of Rotterdam toughened measures, the Port of Hamburg emerged as a new target for smugglers. Therefore, cooperation is key. A good example is the European Ports Alliance (European Commission 2024), which seeks joint responses to drug trafficking and organised crime. Expanding these alliances to include major Latin American ports would strengthen trade networks, improve security, and facilitate the exchange of knowledge and best practices. Similarly, innovations in advanced tracking technologies – from point of origin to final destination – can enhance supply-chain transparency and safeguard important shipment routes, but this requires cooperation from both sides. Counteracting transatlantic drug trafficking and its negative social, economic, and political effects must be seen as a shared responsibility that requires joint responses.

Defending the Defenders

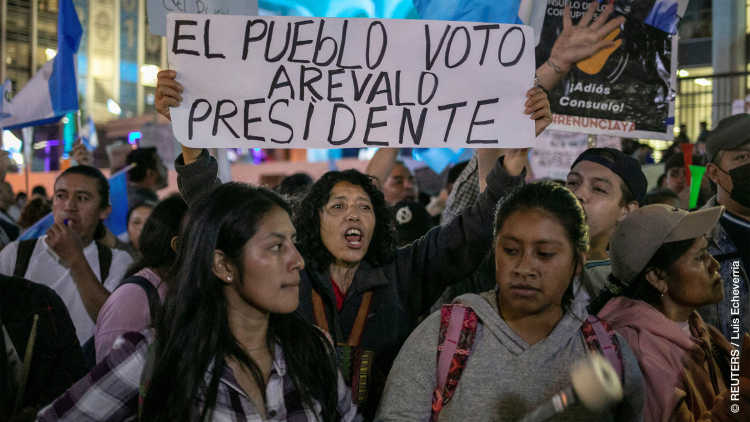

Across the region, defenders of human rights and civil liberties have long been primary targets of political violence. External support and solidarity are urgently needed, including diplomatic engagement – such as embassy presence at trials that often lack due process and the inclusion of threatened social actors in the programmes of official visits. The election of Bernardo Arévalo as president of Guatemala is an example of democratic change indeed being possible, but it also underscores the challenges democracy faces if non-democratic actors remain in key positions. Given the entrenched power structures in the country, activists for human rights and democracy continue to face pervasive threats. Those compelled to seek refuge abroad under the previous president remain unable to return.

In recent years, Germany has established various temporary-protection programmes for people persecuted in their home countries. This includes the Elisabeth Selbert Initiative (ifa), which is funded by the Federal Foreign Office and offers safe haven to human rights defenders, as well as programmes for persecuted journalists (Hannah Arendt Initiative, DW Akademie), cultural workers (Martin Roth Initiative, ifa), and academics (Hilde Domin Programme, DAAD; Philipp Schwartz Initiative, AvH.

As the political conditions making these programmes necessary are likely to endure for the foreseeable future, funding should be secured on a more long-term basis to allow for adequate planning. Beyond that, these programmes also often struggle with what to do when the temporary safe-haven agreement expires but the situation in the persecuted person’s country does not allow for safe return. Here, Latin America seems particularly well suited to options that offer refuge in the region itself, thus allowing those persecuted to remain closer to the social networks of their home countries. Last August, the Hannah Arendt Initiative together with a local partner organisation opened the House for Free Journalism in Costa Rica as a working space for exiled journalists from other Latin American countries. Funding should be provided so that other initiatives may follow up on this experience and establish similar projects elsewhere in the region. The cost of these programmes is comparatively low, but they hold great potential benefit not only for the individuals in question but also as part of Germany’s projection of foreign policy goals abroad.

Culture and Science: Bonds with Latin American Societies

The Trump administration is dismantling the soft-power structures the US had built up over decades. Many in the US foreign policy community, even in its conservative and “hawkish” sectors, fear that China, Russia, and other non-Western countries will be all too happy to step in; the recent testimony of Evan Ellis (2025) to the US Senate is a telling example. Berlin should do all it can to not exacerbate the withdrawal of the West’s soft power.

Precisely because of the Trump administration’s destructive course, Germany’s – and more broadly, Europe’s – well-established outreach programmes to Latin America are more important than ever. By default, their visibility and impact will be much bigger now than in the past. Often, the size of US institutions such as USAID, the attractiveness of US universities, or the funds the US contributed to multilateral initiatives overshadowed European involvement.

Washington’s retreat from multilateral institutions, such as the World Health Organization and the vaccine alliance Gavi, will have severe repercussions for global healthcare. The German Alliance for Global Health Research (GLOHRA 2025) has warned that without the US contribution (which made up 13 per cent of Gavi’s budget), up to 75 million children will not receive potentially life-saving vaccines over the next five years, with more than a million preventable deaths to occur in consequence. Accordingly, GLOHRA has called on the new German government to uphold its commitment to Gavi and ensure that its vital work can continue.

The recent COVID-19 pandemic showed the extent to which health policy engagement – or the lack thereof – can matter politically (Hoffmann and Drexler 2024). China and Russia scored significant diplomatic wins by making their vaccines available in the early phases of the pandemic when Western states were seen to be hoarding them for themselves. In Latin America and the Caribbean, this was felt particularly strongly as many viewed the West as not living up to its promises of close ties and mutual support. While the US seems bent on repeating this mistake, Europe certainly still has the power and the options to prove a more reliable partner.

Europe and Latin America experienced a moment of alienation not only with the pandemic but also in the divergent responses to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine as well as to the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. In the eyes of many in Latin America, the West’s seemingly unconditional support for the Benjamin Netanyahu government, despite what the International Criminal Court has condemned as Israeli war crimes in Gaza, demonstrates its double standards. For Germany, this is a particularly thorny issue, given the weight of history. But if it is not rectified, it will continue to hamper much-needed efforts towards closer cooperation.

Key assets of Germany’s international profile are its Goethe Institutes, Deutsche Welle, and other institutions of cultural and societal exchange. German cultural programmes are shielded from overly direct political influence and are committed to critical and pluralist approaches. This makes them prominent counter-models to the Trump administration’s crusade against all that is dismissively labelled “woke” or “liberal.”

Over the past few decades, as enrolment in US universities and US job market opportunities increased, Latin American academia became more and more oriented towards the US. Now, as the Trump administration is massively cutting funding for universities and research institutions and striking out against academic liberties more broadly, shockwaves are rippling through Latin American universities. In the words of a colleague, Europe is seen as “a West that has not gone mad.” As a result, Germany now has a chance to attract Latin American students and scholars who otherwise would have regarded the US as the prime career destination. In a moment where “Fachkräftemangel” (a shortage of skilled labour) is a key problem for the German economy, the high standards of Latin American universities offer much promise. Obviously, this would need to be flanked by swift procedures for issuing visas and residency permits.

The long continuity and reliability of DAAD, AvH, and other German academic exchange institutions stands in stark contrast to Trump’s haphazard and disruptive policies. This is the moment to expand academic cooperation, not reduce it. In a most welcome step, the new German government’s coalition agreement explicitly pledges to strengthen both DAAD and AvH. In times of heightened budget constraints, however, it will be crucial to defend these institutions’ budgets so that Germany can live up to this promise. Cultural and academic exchange should not be seen as a cost but rather as an investment to build upon, at a time when the disruption of Europe’s traditional ties to the US makes it imperative to renew and strengthen partnerships with the countries of the Global South, particularly with Latin America and the Caribbean.

Footnotes

References

CDU/CSU/SPD (2025), Verantwortung für Deutschland, Koalitionsvertrag zwischen CDU, CSU und SPD, 21. Legislaturperiode, accessed 16 April 2025.

Drezner, Daniel W., Henry Farrell, and Abraham L. Newman (eds) (2021), The Uses and Abuses of Weaponized Interdependence, Washington, DC: Brookings.

Ellis, Evan (2025), PRC Influence and the Status of Taiwan’s Diplomatic Allies in the Western Hemisphere, Statement before the Foreign Relations Committee Subcommittee on Western Hemisphere, Transnational Crime, Civilian Security, Democracy, Human Rights, and Global Women’s Issues, 18 March, Washington, DC, accessed 16 April 2025.

European Commission (2024), European Ports Alliance to Fight Drug Trafficking and Organised Crime, 24 January, accessed 16 April 2025.

GLOHRA (German Alliance for Global Health Research) (2025), Appell an die Bundesregierung zur Sicherung der Finanzierung von Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, accessed 3 April 2025.

Hoffmann, Bert, and Felix Drexler (with Antoní Plasència and Elizabet Diago Navarro) (2024), Shared Challenges, Shared Responsibilities: Lessons Learnt for EU-LAC Cooperation in Global Health, EU-LAC Policy Brief No 8, 13 December, Hamburg: EU-LAC Foundation, accessed 16 April 2025.

Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) (2024), IACHR Expresses Concerns over Judiciary Reform in Mexico and Warns of Threats to Judicial Independence, Access to Justice, and Rule of Law, 12 September 12, accessed 16 April 2025.

Ministério da Fazenda (2024), Novo Brasil - Ecological Transformation Plan, accessed 16 April 2025.

OECD (2024), Latin American Economic Outlook 2024: Financing Sustainable Development, 9 December, OECD Publishing, Paris, accessed 16 April 2025.

Editor GIGA Focus Latin America

Editorial Department GIGA Focus Latin America

Regional Institutes

How to cite this article

Hoffmann, Bert, Jonas von Hoffmann, Sabine Kurtenbach, Mariana Llanos, Janaina Maldonado Guerra da Cunha, Tomas Costa de Azevedo Marques, Detlef Nolte, Désirée Marlen Reder, Samuel Siewers, and Cordula Tibi Weber (2025), Latin America: Germany’s Indispensable Partner, GIGA Focus Latin America, 2, Hamburg: German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), https://doi.org/10.57671/gfla-25022

Imprint

The GIGA Focus is an Open Access publication and can be read on the Internet and downloaded free of charge at www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publications/giga-focus. According to the conditions of the Creative-Commons license Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0, this publication may be freely duplicated, circulated, and made accessible to the public. The particular conditions include the correct indication of the initial publication as GIGA Focus and no changes in or abbreviation of texts.

The German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) – Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien in Hamburg publishes the Focus series on Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and global issues. The GIGA Focus is edited and published by the GIGA. The views and opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the institute. Authors alone are responsible for the content of their articles. GIGA and the authors cannot be held liable for any errors and omissions, or for any consequences arising from the use of the information provided.