- Home

- Publications

- GIGA Focus

- Closing Spaces: The Last Bulwark of Nicaraguan Civil Society under Attack

GIGA Focus Latin America

Closing Spaces: The Last Bulwark of Nicaraguan Civil Society under Attack

Number 1 | 2023 | ISSN: 1862-3573

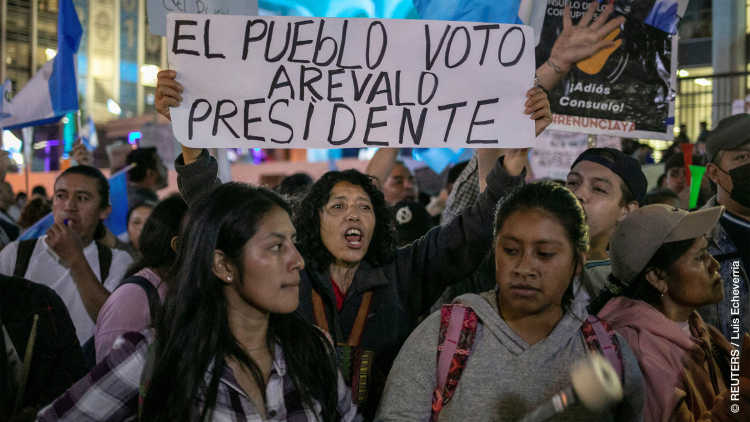

Since 2018, the Daniel Ortega regime has led a systematic campaign of repression against Nicaragua’s once-vibrant civil society. Now it is attacking the last sanctuary of dissent: the Catholic Church. The latest arrests of clerics in Nicaragua resulted in international outrage. Pope Francis, who had long remained silent on the situation in Nicaragua, expressed his sincere concerns.

The comprehensive attacks against the Church are but another step in Ortega’s tightening authoritarian grip on the country. Since 2018, when nationwide street protests erupted, repression has characterised daily life in Nicaragua. The regime’s strategies of repression have evolved from indiscriminate violence against all stirrings of protest to more targeted forms of clamping down on dissent.

Some 396 state-driven acts of aggression against the Church in Nicaragua have been reported since April 2018. At the time of writing, 11 clerics are under arrest, at least two have been expelled, eight were denied re-entry to the country, and various Church-run media outlets have been shut down. The Catholic Church had been the last space where protest against state repression was still voiced.

Ortega’s “Christian rebirth” in his 2006 electoral campaign was key to his return to power. The current wave of repression against the Church marks a break with this alliance.

The recent wave of repression could backfire, with high costs for the government: in a predominantly Christian society, these attacks on the Church have caused indignation – even within the ruling party’s own ranks.

Policy Implications

The Catholic Church needs to live up to its values and stand up to the Ortega regime. The European Union has imposed sanctions; however, it should pressure international organisations such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund to end loans to the regime that help stabilise its power. With universities having been closed, the EU should facilitate exiled Nicaraguan students finishing their degrees in Europe.

From Social Unrest to Mass Repression

In 2018, two seemingly minor incidents sparked a spiral of dissent. A handful of environmental and indigenous activists gathered in the Nicaraguan capital Managua in early April to protest against the government’s mishandling of a wildfire in the nature reserve Indio Maíz. A few days later, a group of retirees expressed their disagreement with the government’s social security reform (INSS) plans that would cut their pensions significantly. Both peaceful protests were small in size, limited to specific social groups, and without clear leadership – factors which in most cases speak to such demonstrations’ short life span as well as to modest both domestic and international attention being paid to them.

However, disproportionate and violent repression by paramilitary groups linked to the government and, a bit later, by the country’s police forces caused widespread indignation. People mobilised in solidarity across social groups and broadened the demands being made, coming to include explicitly political ones such as early elections. Instead of inhibiting further protest, the repression witnessed backfired (Kurtz and Smithey 2018): the nationwide, large-scale peaceful protests, which were broadcast live via social media, put the spotlight on the crackdown taking place and exposed the regime’s wrongdoings as much nationally as internationally.

A key event illustrating the intimidating and brutal state-driven violence occurring was the Mother’s Day celebrations of 30 May 2018, when thousands – and often entire families – protested in Managua in solidarity with the mothers who had lost children in the clashes of the previous weeks. Reports describe snipers and masked individuals using automatic and semi-automatic weapons to shoot at the marchers, resulting in heavy bloodshed with 19 people killed. This and similar incidents of indiscriminate, widespread violence against peaceful protesters happened at a time when officially a ceasefire had been declared in the context of two roundtable negotiations – the so-called National Dialogue – in May and June 2018 respectively. Besides mass shootings, arrests, and trials with long jail sentences, the government’s repertoire to quell protests also included a ban on public demonstrations and an array of intimidation tactics. The powerful vice-president Rosario Murillo, wife of President Daniel Ortega, verbalised this open brutality when ordering coercive state actors to “vamos con todo” – let’s go with all means.

The government’s campaign of repression not only impacted Nicaraguan society. It also put the Ortega regime in the spotlight vis-à-vis the international community. As a result, many countries condemned the state-driven violence, and different rounds of sanctions, especially by the United States, the European Union, and Canada, would follow.

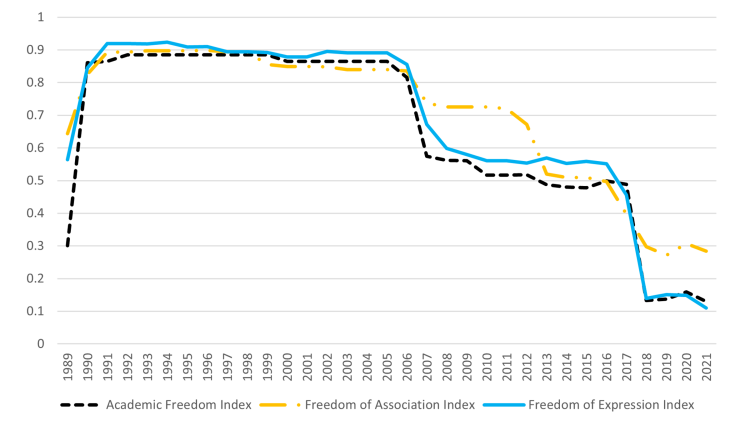

Targeted Repression – Eliminating (Potential) Threats

Despite being outlawed, protests continued throughout 2019 and 2020 in different forms. Aiming to avoid the political costs of arbitrary repression, Ortega and Murillo turned to a more refined strategy. Cracking down on dissent evolved from indiscriminate violence to more targeted forms of repression, focusing on those sectors and persons who dared to criticise the government and/or could represent a potential threat to the presidential couple’s grip on power. Especially critical media and non-governmental organisations became targets of the state apparatus, deepening the process of autocratisation playing out in the Central American country.

For the year 2021 alone, 1,520 attacks against the freedom of the press were reported, including 16 arbitrary detentions (eight of those concerned remain in prison to this day). Others were subject to threats against their families and own persons, while editorial offices were besieged, ransacked, and essential working equipment confiscated. As a result, all independent print media (e.g. Confidencial, La Prensa, El Nuevo Diario) were closed (PCIN 2021) and at least 160 journalists had to go into exile (PEN International 2022). The few remaining independent outlets operate under self-censorship and focus on innocuous topics, helping the regime to control the narrative. Meanwhile, some journalists and media houses try to continue their work by informing the Nicaraguan people from outside of the country via online outlets and social media platforms – which the regime does not yet have control over.

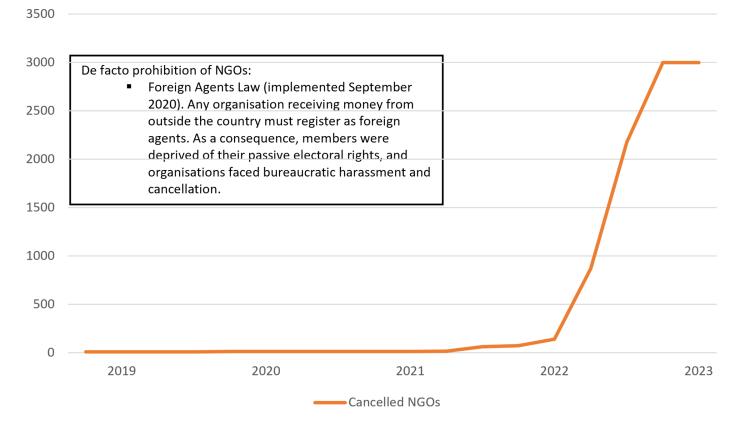

Simultaneously, the latter has attempted to keep up the façade of democracy, passing laws legalising its acts of repression and criminalising the freedom of expression, association, movement, and political participation (Orozco 2022). The so-called Foreign Agents Law of 2000 would be used to de facto ban 43 per cent of NGOs present in the country by December 2022. Therewith, the operating licences of more than 3,000 international and domestic such entities were cancelled (Orozco 2022).

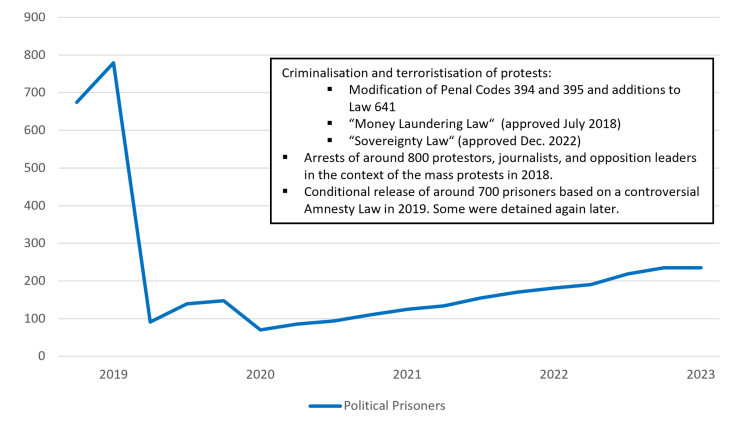

In the run-up to the elections of November 2021, the ruling couple sought to eliminate all potential opponents and presidential hopefuls. The above-mentioned law requires all institutions receiving funds from foreign sources to register as foreign agents and strips their employees and members of their passive electoral rights. More than 50 prominent people were imprisoned and many opposition leaders condemned to sentences of up to 13 years based on either the “Cybercrime” Law defining critical online opinions as hate crimes or on the “Sovereignty” Law (both of December 2020) that framed opposition parties and opposition politicians as traitors and terrorists.

These laws can be used against any kind of critic. In consequence, court hearings are increasingly being orchestrated and the number of political prisoners is growing steadily. Jail conditions have been criticised as inhumane for the lack of medical care offered as well as use of solitary confinement and torture, further to the harassment also of inmates’ family members when rare visits are allowed (Casla Institute 2022).

As a result, in the presidential elections of 2021 Ortega ran practically without competition. The organisation Urnas Abiertas (2021) calculated a national voter abstention rate of 81.5 per cent and denounced the elections as neither fair nor free in being accompanied by political violence, intimidation, and electoral fraud. On the inauguration of his current term in office, Ortega suggested “to wipe the slate clean” and “[to] continue the good path we were on until April 2018” – that is, before the eruption of protests. However, those interpreting his speech as a call for “a new beginning” have since been disappointed. Not only did state violence and repression continue but also the 2022 municipality elections would prove no less of a farce, as marked by electoral fraud and with 82.67 per cent of Nicaraguans abstaining according to Urnas Abiertas (2022).

Figure 1. Cancellation of NGOs since 2018

Source: Author‘s own elaboration based legislative decrees of the Ministry of the Interior (Migob) published in the Legislative Gazette and news reports.

Figure 2. Political Prisoners

Source: Author‘s own elaboration based on data of Presas y Presos Politicos Nicaragua.

Attacking the Last Sanctuaries of Social Protest

After entering a fourth consecutive term in office, the autocratic regime of Ortega and Murillo launched its attack on the education sector in closing 22 non-state university organisations across the country – including 12 universities. The latter’s resources were confiscated, and their existence replaced by three new universities under party control. Among them is the Universidad Politécnica de Nicaragua (UPOLI), a key focal point during the protests of April 2018. In addition, the Central American University (UCA), another cradle of the 2018 protests, suffered attacks as the regime cut its budget and stripped it of all public funds (Peña 2022).

At least 14,000 students would be affected by these measures. Many sought to continue their studies at Nicaragua’s private universities after being expelled from public ones for their participation in the protests. When this alternative was also closed off, it left them without the possibility of finishing their degrees – a similar fate to fellow students who earlier had to flee the country. Additional measures curtailed academic freedom and the right to education. One example is the reform in 2022 of the Law on the Autonomy of Higher Education of 1990, now requiring the academic programmes of all universities to undergo a politically motivated approval process by a central state body (UNHRC 2022, paragraph 13).

These measures can be seen as revenge for the universities’ high-profile role in the protests. But they are also as an intended deterrent. The Ortega-Murillo regime has become aware that educational spaces where critical discussions are encouraged threaten its illegitimate grip on power.

The closing of civic space did not stop with the country’s universities. The next institution on the regime’s radar was the Catholic Church. Already during the protests, the Church had suffered some individual attacks; in 2022, however, the Catholic Church as an institution was now targeted. In March, the Vatican’s ambassador, Apostolic Nuncio Stanislaw Sommertag, saw his diplomatic approval withdrawn and was expelled from the country. Likewise, the Missionaries of Charity, founded by Mother Teresa of Calcutta, were driven out of the country, while at least 11 clerics have been denied re-entry when returning from abroad. Also, religious rituals were impeded, processions forbidden, and Church services disturbed by police and riot groups. Some 20 radio and television outlets overseen by the Church saw their operations cease.

In raiding the media outlet of the Divina Misericordia Church in Matagalpa, the sanctuary itself, with seven people inside without food or electricity, was besieged by police and anti-riot troops. When the bishop of the respective dioceses started a hunger strike in protest at police harassment, his Curia was also besieged and he was prevented from celebrating mass. Bishop Rolando Álvarez (one of the bishops that, together with Silvio Báez, had mediated the National Dialogue in 2018), as well as five priests and six lay people were detained under the accusation of “organising violent groups” and encouraging them “to carry out acts of hate against the population” (UNHRC 2022). Ever since, Bishop Álvarez has remained incommunicado under house arrest accused of “conspiracy” and “spreading false information.” He is scheduled to have a court hearing on 10 January 2023. Other clerics would be arrested under the criminal code, on the basis of accusations that appeared clearly orchestrated.

While some observers were unsurprised by the move, for others it was unexpected – primarily because of the potentially high costs ensuing for the government. The regime might not have foreseen the extent to which this move could potentially backfire. In a predominantly Christian society, the attacks on the Church caused indignation – even among the ruling party’s own rank and file.

The sequence of events shows a systematic, step-by-step crackdown on all those who have opposed or voiced criticism against Ortega and Murillo since 2018. The frontal attack against the Church is particularly remarkable considering that the re-election of Ortega in 2006 depended to a considerable extent on the former’s support. To better understand the regime’s rationale, it is necessary to take a look not only at the role of the Church in Nicaragua in the protests of April 2018 but also the historic relationship between it and the state there.

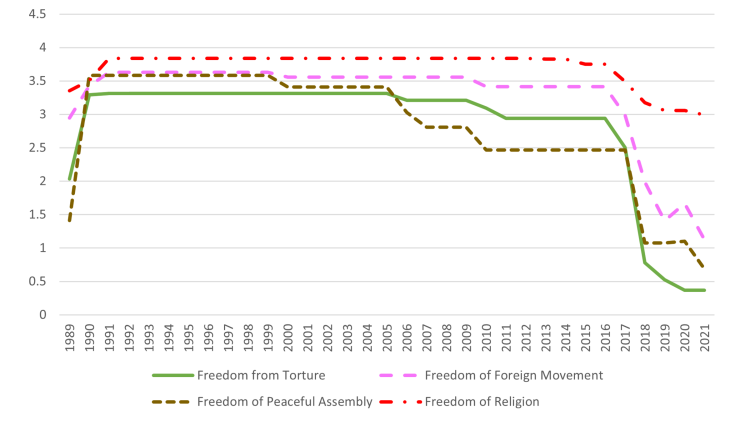

Figure 3. Evolvement of Rights and Freedoms

Source: University of Gothenburg, Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project.

Figure 4. Closing Civic Spaces

Source: University of Gothenburg, Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project.

The Historic Link between the Church and Politics

During the 43-year autocratic dynasty of the Somoza family (1936–1979), as characterised by corruption, oppression, and the brutal persecution of opponents, the Church was for the most part an opportunistic ally of the incumbent regime. In the last six months alone before the overthrow of Anastasio Somoza by the Sandinista Revolution in 1979, the Church celebrated 200 masses for the dictator’s long life (Aragón 2011). Starting in 1970, a part of the Church distanced itself from Somoza. This process correlated with the naming of Cardinal Miguel Obando y Bravo as Archbishop of Managua, an individual who had gained much respect among the population as an outspoken critic of Somoza.

Popular discontent crystallised in various opposition alliances. While some hoped for peaceful solutions, others turned to armed struggle – led since 1961 by the Frente Sandinista de la Liberación Nacional (FSLN) or Sandinistas for short, a guerrilla organisation based on Marxist-Socialist ideology. Ortega was one of the FSLN’s nine commanders. In the 1970s, the Catholic Church was divided on the question of whether to support the revolutionary movement or not. Liberation Theology tried to reconcile the armed guerrilla struggle with Christian values. On this basis, the Christian Revolutionary Movement, consisting of students of faith-based schools and universities, came to support the FSLN. While some priests celebrated mass honouring the dead guerrilla fighters, others were critical of the Sandinistas – most prominently, Cardinal Obando y Bravo. Only shortly before the ouster of Somoza, the National Conference of Bishops (Conferencia Episcopal de Nicaragua, CEN) publicly supported the revolutionary struggle (Equipo Envío 1983).

After the fall of Somoza in 1979, the FSLN established a revolutionary military government, the Junta Government of National Reconstruction, composed of five leaders, among them Ortega. In 1985, he became Nicaragua’s first elected president. Meanwhile, the civil war between the FSLN and its US-backed opponents, the so-called Contras, continued unabated. Despite their alliance during the revolutionary struggle and the prominence of Liberation Theology priests like Ernesto Cardenal, over time the Church hierarchy became a fierce opponent of the Sandinista leadership and thus subject to repression. In this sense, essentially two churches existed in Nicaragua (Aragón 2011). Similarly, the FSLN was divided in its opinion on the Church and on religion in general. A statement by the FSLN’s National Directorate in 1980 indicates that some FSLN leaders saw religion as a means of oppression and of justification for class hierarchies (Dirección Nacional del FSLN 1980).

After the peace agreement of 1990, mediated by Cardinal Obando y Bravo on behalf of the Church, the FSLN lost in the country’s next three rounds of elections (1990, 1996, and 2001). In this period, Cardinal Obando y Bravo used his authority to rally against the FSLN. This, however, changed with Ortega’s campaign during the run-up to the 2006 presidential elections he would eventually win.

Four factors contributed to Ortega’s victory. First, constitutional changes resulting from a pact with his predecessor, Liberal Party leader Arnoldo Alemán, which lowered the percentage needed to win the elections (the Liberal Party had lost the public’s trust due to repeated corruption scandals). Second, the support of the Church. Third, the reconciliation with the business sector. Fourth and finally, the new image the electoral campaign crafted of Ortega.

When the Church sold its principles, and Ortega’s Christian rebirth

In a remarkable break with the past, the 2006 campaign, managed by Ortega’s wife Murillo, presented him as business-friendly, a man of peace instead of protagonist of the civil war, and as a good Christian. As such, he could reconcile with the business sector and some members of the Contras, giving them political power. In addition, he publicly asked the Church and its representatives for forgiveness. This reconciliation was symbolised in the Christian marriage between Ortega and his long-term companion Murillo, overseen and blessed by Cardinal Obando y Bravo. Furthermore, they adapted their public discourse – adding Christian rhetoric and symbols to all their activities and language henceforth (Espinoza Rizo 2021).

In the run-up to the 2006 elections the National Assembly, dominated by the FSLN and its allies, passed a bill banning abortion – a measure the Church had long pressed for. This law was promoted by Ortega, who, in the 1980s, had strongly supported abortion rights. To secure the Church’s continued backing, in a similar vein Ortega guaranteed that same-sex marriage would not be legalised, strengthening the concept of the traditional family. The regime further distributed perks among the religious authorities. Ortega was aware that he relied on the Church’s support to win the elections and knew how to make full use of it. Being aware of the Church’s reverence among the Nicaraguan population, Ortega and Murillo were prudent to maintain good relations with it and its representatives in the years that followed. The Church thus let itself be instrumentalised for small gains or to push through its “heart topics.”

While in the past almost all Nicaraguans had been Catholic, the country’s religious landscape would become more diverse with the passing of time. Nonetheless, Christianity – particularly the Catholic Church – remains deeply rooted in Nicaraguan society. Also, the FSLN’s rank and file are overwhelmingly Christian: more than half are Catholic, while around 40 per cent adhere to the mushrooming evangelical churches. Hence, certain Church representatives speaking out against the regime or aligning themselves with the protests would constitute a major problem for the Ortega-Murillo government.

The Church in Turmoil

Since April 2018, the Catholic Church and its members have taken different roles in the protests and positions towards the government. However, it is necessary to distinguish between the Church hierarchy and its institutions and individual priests. Already in that month, some church leaders would support and protect the protesters (Sismologia Social 2021). Monsignor Báez and Cardinal Leopoldo Brenes immediately called for an end to the violence, while Monsignor Álvarez declared that he would stand by the protesters and their cause. Priest Enrique Martinez Gamboa of Leónhad accompanied the civic protests during Mother’s Day 2018, publicly encouraging those involved and denouncing the state-driven violence (he has been in prison since October 2022). During these events, some churches opened their gates to wounded protesters or relatives of political prisoners on hunger strike. Such public gestures of support bestowed the movement with legitimacy vis-à-vis both the Nicaraguan people and the international community.

The CEN mediated the National Dialogue in 2018 at the request of the Ortega government. However, after the failure of these negotiations the CEN withdrew from the political and public scene and abstained from the National Dialogue of 2019. This stepping back may be explained by fear of repression, with an increase in harassment and threats against clerics – in particular Monsignor Báez, who fled the country.

In the following years, the institutionalised Church remained silent while individual religious leaders continued to speak out against repression and to support the opposition. In August 2022, when repression against its representatives escalated, the CEN and the Vatican found their voice again but remained hesitant in making their declarations. As a consequence, the Church has been sharply criticised by Nicaraguan civil society organisations and human rights activists.

Some individual clerics, in particular Bishop Báez, immediately denounced the arrest of their colleagues and condemned “the acts of the dictatorship” in the strongest possible terms. On the contrary Cardinal Brenes, currently the highest representative of the Catholic Church in Nicaragua, has remained reticent about speaking out. After his encounter with Pope Francis at the Vatican, they jointly declared their hope for a peaceful solution to the situation and announced that dialogue should continue. Recently it became known to the public that the Church and the regime are in conversation, which might be the reasoning behind the chosen stance of Cardinal Brenes and the Pope. The Nicaraguan Human Rights Center strongly denounces that there is dialogue taking place with the regime without the country’s civil society or population knowing about either the fact or the contents of these talks (CENIDH 2022).

Perspectives and Outlook

Regime repression shows a horrifying state of affairs to exist. Independent media outlets were besieged, ransacked, and shut down, and their journalists attacked and arrested; in the run-up to the 2021 presidential elections, every potential rival candidate was persecuted; tailor-made laws gave justification to silencing any critical voice emerging in the country. To date, 355 people have been killed (with impunity), there are 220 political prisoners, 3,000 NGOs have closed down, the regime has staged two fraudulent elections, and an estimated 604,485 Nicaraguans have fled the country between 2018 and 2022.

Since 2018, the international community has tried to pressure the regime into abandoning its authoritarian path. The Organization of American States has issued a number of resolutions (the latest were unanimous) condemning the human rights violations and undemocratic conduct of the Ortega-Murillo regime. Various initiatives at negotiation have failed, for instance that by the Civic Alliance in 2019 or by Colombian President Gustavo Petro (himself a former guerrilla member) for the release of 14 political prisoners in 2022.

Additionally, various rounds of sanctions, especially by the US and the EU, have increased the pressure. These measures were mostly targeted against the regime’s inner circle as well as against key industries (e.g. gold mining), with little impact on broader Nicaraguan society. The US has not yet enforced the RENACER Act, which, among other measures, would exclude Nicaragua from the free trade agreement CAFTA.

A negotiated solution to the crisis, ending the repression and freeing the country’s political prisoners, would doubtlessly be the preferable approach. History shows that the Catholic Church might have a role to play in such negotiations even despite recent developments. So far, however, the regime’s actions raise doubts that it is prepared to make any concessions. In this sense, Monsignor Baéz suggested that dialogue with the regime might be of little use as Ortega “does not respect anyone.” One of his latest declarations appear to underline this assumption: Ortega called the Catholic Church a “perfect dictatorship” and Pope Francis the “Holy Tyrant” in reaction to condemnations of his regime style.

Although not closing the door to a negotiated solution is prudent, other factors are ultimately more likely to be successful. One of these is an internal implosion provoked by a combination of keeping the spotlight on the regime’s wrongdoings and more consequent sanctions – the World Bank, International Monetary Fund, and the Central American Bank for Economic Integration (CABEI) are still de facto funding the regime – that would deprive the government of the necessary funds to pay their coercive forces. It would also make even loyalists come to doubt the state apparatus and leadership.

Besides that, Nicaraguan society is still deeply divided – not only as a result of developments since the protests of April 2018 but already as a legacy from the Sandinista Revolution and Contra War indeed. The cruelties and injustice of the 1970s and 1980s have never been dealt with, remaining taboo to speak of. The events of 2018 resulted in additional divisions. Thus, a profound process of transitional justice is also necessary.Reconciliation does not mean forgetting like happened after the civil war, but rather coming to terms with events – nurturing remembrance, justice, and the grounds for compromise.

The future of the country can only be shaped by Nicaraguan society itself. Therefore, it is crucial that the Nicaraguan youth – many of whom had mobilised against the regime in 2018 and are now in exile – get a chance to pursue their education and finish their degrees. At this point, European countries should take responsibility and dismantle the bureaucratic barriers preventing Nicaraguan students from entering European universities.

Footnotes

References

Aragón, Rafael (2011), ¿Es Cristiano El Proyecto Del Gobierno de Daniel Ortega? ¿Y Cuál Es El Proyecto de La Iglesia?, in: Revista Envío, 349, April, accessed 3 Januar 2023.

Casla Institute (2022), Comunicado urgente sobre la situacion de los presos politicos en Nicaragua, Tamara Suju, Tweet, accessed 3 January 2023.

CENIDH (2022), Dialogo entre régimen y iglesia, Tweet, accessed 3 January 2023.

Dirección Nacional del FSLN (1980), Comunicado oficial de la direccion nacional del F.S.L.N. sobre la religion, 7 October, FSLN National Directive, accessed 3 January 2023.

Equipo Envío (1983), La Iglesia Católica en Nicaragua después de la revolución, in: Revista Envío, 30, December, accessed 3 January 2023.

Espinoza Rizo, Álvaro Augusto (2021), Las Iglesias ante la violencia estatal en las protestas contra el gobierno sandinista en Nicaragua (desde abril de 2018 hasta la actualidad), in: Christine Hatzky, Sebastian Martínez Fernández, Joachim Michael, and Heike Wagner (eds), Las Iglesias ante la violencia estatal en las protestas contra el gobierno sandinista en Nicaragua (desde abril de 2018 hasta la actualidad), Argentina: Editorial Teseo, accessed 3 January 2023.

Kurtz, Lester R., and Lee A. Smithey (eds) (2018), The Paradox of Repression and Nonviolent Movements, Syracuse University Press, accessed 3 January 2023.

Orozco, Manuel (2022), Dictatorial Radicalization in Nicaragua. From Repression to Extremism?, Washington, DC: Inter-American Dialogue, accessed 3 January 2023.

PCIN (2021), Informe Anual 2021 Sobre Agresiones a La Prensa Independiente, Periodistas y Comunicadores Independentes de Nicaragua, accessed 3 January 2023.

PEN International (2022), Eye on Nicaragua – Observatory, 15 December, accessed 3 January 2023.

Peña, Marco Aurelio (2022), El poder estatal contra la libertad académica en Nicaragua – Agenda Estado de Derecho, Agenda Estado de Derecho (blog), 24 May, accessed 3 January 2023.

Sismologia Social (2021), La Iglesia en la oleada de protestas de 2018, sismologiasocial.com (blog), 1 August, accessed 3 January 2023.

UNHRC (2022), Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on Situation of Human Rights in Nicaragua, A/HRC/51/42, accessed 3 January 2023.

Urnas Abiertas (2022), Nicaragua Observa: 6 de Noviembre 2022, 5, accessed 3 January 2023.

Urnas Abiertas (2021), Radiografía de La Farsa Electoral, 9, 22 November, accessed 3 January 2023.

Editor GIGA Focus Latin America

Editorial Department GIGA Focus Latin America

Regional Institutes

Research Programmes

How to cite this article

Reder, Désirée (2023), Closing Spaces: The Last Bulwark of Nicaraguan Civil Society under Attack, GIGA Focus Latin America, 1, Hamburg: German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), https://doi.org/10.57671/gfla-23012

Imprint

The GIGA Focus is an Open Access publication and can be read on the Internet and downloaded free of charge at www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publications/giga-focus. According to the conditions of the Creative-Commons license Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0, this publication may be freely duplicated, circulated, and made accessible to the public. The particular conditions include the correct indication of the initial publication as GIGA Focus and no changes in or abbreviation of texts.

The German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) – Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien in Hamburg publishes the Focus series on Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and global issues. The GIGA Focus is edited and published by the GIGA. The views and opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the institute. Authors alone are responsible for the content of their articles. GIGA and the authors cannot be held liable for any errors and omissions, or for any consequences arising from the use of the information provided.