- Home

- Publications

- GIGA Focus

- The European Union and Latin America: Renewing the Partnership after Drifting Apart

GIGA Focus Latin America

The European Union and Latin America: Renewing the Partnership after Drifting Apart

Number 2 | 2023 | ISSN: 1862-3573

In a press conference in Buenos Aires in October 2022, Josep Borrell, the European Union High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, declared that 2023 must be the year of Latin America in Europe and of Europe in Latin America. There is renewed European interest in Latin America as a strategic partner, but many Latin American governments prefer an active non-alignment in international politics.

The Spanish EU Council Presidency in the second half of 2023 will open a window of opportunity for deepening EU–Latin American and the Caribbean relations. A summit between the EU and the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC), the first since 2015, is planned to be held from 17–18 July 2023 in Brussels.

As the EU is pursuing open strategic autonomy, Latin America is perceived as a possible strategic partner supportive of its agenda in international politics. Strategically important raw materials are imported from Latin America, and the latter’s countries have the potential to become important producers and exporters of green hydrogen.

While Europe has lost ground as a trading partner with Latin America to China, European companies are still a leading investor in the region, and Europe has still soft power or power of attraction in Latin America.

The results of the recent elections in Latin America, especially the victory of Lula da Silva in Brazil, open new possibilities for EU cooperation with the region. It will be easier to find common positions on climate change and the protection of the Amazon rainforest.

But Latin American governments will demand more protection for their domestic industries in free trade agreements and expect more European funding for measures against climate change and for environmental protection, and they will not automatically support European positions in international politics.

Policy Implications

If the EU wants to win over Latin America as a strategic partner, it must also act strategically. The signing of the association agreement with Mercosur should take highest priority, even in the face of resistance from within Europe. The upcoming EU-CELAC summit offers an opportunity to adopt a new agenda of bi-regional cooperation.

A Renewed European Interest in Latin America

There is no doubt that the strategic value of Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) has increased for the European Union since the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. Politically, LAC governments are important when it comes to voting on resolutions on Russia in the United Nations General Assembly. Economically, Latin America has raw materials (for example, natural gas and oil) that Russia supplies to the EU. Strategically, important raw materials are already imported from Latin America such as fluorspar (25 per cent from Mexico), niobium (85 per cent from Brazil), and lithium (78 per cent from Chile), which, as in the case of the latter, are crucial for the green transformation of European economies. Based on its climatic (sunshine and wind) and geographic conditions (ample space and proximity to ports), LAC is considered to have the largest potential to produce and export green hydrogen at competitive prices among the different regions of the world. And Europe is one of the biggest future markets for green hydrogen.

In mid-July 2022, the Spanish foreign minister, José Manuel Albares, argued that Latin America is by far the most Europe-compatible region on the planet. And he claimed that the signing of the EU-Mercosur association agreement and the modernisation of the trade agreements (to keep pace with new trade and investment standards and patterns, for example as related to digital trade) with Chile and Mexico should take high economic and political priority because they would represent a “strategic deepening of the EU” vis-à-vis Latin America. A few days later, the EU’s Foreign Affairs Councilagreed to “bring about a qualitative leap in the relations between the EU and LAC countries” and to hold an EU-Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) foreign ministers meeting in Buenos Aires in October 2022with the aim of preparing for an EU-CELAC summit with the heads of government in 2023.

The last EU-CELAC summit had taken place in Brussels in 2015; its successor in El Salvador scheduled for 2017 was cancelled due to the internal conflicts in Latin America (mainly the crisis in Venezuela). In the two years that followed, CELAC remained paralysed. Then during Mexico’s pro tempore presidency (2020–2021) CELAC was revived, and, in September 2021, the first presidential summit since January 2017 held. In this respect, CELAC became interesting again as an interlocutor for the EU. The Argentine government, which held the CELAC pro tempore presidency in 2022 (and holds the pre tempore presidency of Mercosur in the first semester of 2023), has actively sought to resume inter-regional dialogue. On the European side, the Spanish presidency of the Council of the EU in the second half of 2023 should have a positive impact on relations with Latin America, as was the case during former Spanish EU presidencies (in 1989, 1995, 2002, and 2010).

The CELAC–EU 3rd Foreign Ministers Meeting in Buenos Aires

On 27 October 2022, more than four years after their last meeting, the foreign ministers (mostly their representatives) of 60 countries from Europe and LAC met in Buenos Aires. Josep Borrell, the EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, made his noted statement on the “Year of Latin America in Europe” (and vice versa). What are the most important outcomes from the CELAC–EU 3rd Foreign Ministers Meeting? First, bi-regional dialogue has been resumed with a renewal of the related agenda,although a lot of things remain very vague. Second, a timetable was set for activities in 2022 and 2023, including a summit in Europe in the second semester of 2023. Third, there was open debate, also on issues on which there was no consensus with different views on both sides.Fourth, the debate was not dominated and overshadowed by the question of the participation or not of LAC’s non-democratic governments,as had happened at other meetings in the recent past.

But this does not take the issue of how to deal with authoritarian regimes in Latin America off the table. There will be no EU-CELAC summit excluding these countries. However, the EU should not refrain from openly criticising human rights violations in Latin America(as some governments in the region are also doing). Other potential points of conflict also became apparent. First, even if CELAC under Mexican and Argentinean leadership has overcome its paralysis, Latin American regionalism remains in crisis and the question arises as to who speaks for LAC and how binding agreements really are.Unlike the EU, CELAC is not a regional organisation but a regional forum, with varying degrees of willingness on the part of member states to take part and engage.Under Jair Bolsonaro, for example, Brazil stopped participating. Due to bilateral or domestic conflicts, some presidents did not attend the CELAC summit held in Buenos Aires at the end of January 2023.

Second, the European interest in importing mainly strategic raw materials (such as lithium) and energy (fossil fuels and green energy) from Latin America may clash with the latter’s own interest in reindustrialisation. Third, tensions and contradictions may arise between Europe’s geopolitical interests in Latin America and European climate diplomacy.This is exemplified by the EU-Mercosur association agreement (see Nolte 2021), which has been negotiated in principle since June 2019 but is currently still waiting to be signed. Fourth, there are clear differences between some Latin American governments and the EU in terms of defining and protecting democracy and human rights. Common values are often invoked in Sunday speeches, but practice is different.

Fifth, there is no common position in LAC (Mijares 2022), and between the EU and LAC (e.g. on sanctions), regarding the war on Ukraine.The joint communiqué avoided naming and condemning Russia as European governments had hoped.At least the participating governments were able to reaffirm their support for the objectives and principles enshrined in the UN Charter “to defend the sovereign equality of all States and respect their territorial integrity and political independence.”But conflicts of interest and differing assessments of the Ukraine conflict persist.This may also have something to do with the fact that the EU sees Latin America as a “natural” partner for its open strategic autonomy.In Latin America, on the other hand, the idea of an active non-alignment is propagated, which stands in the way of a strategic alliance with Europe.

Open Strategic Autonomy versus Active Non-Alignment

The experience of United States unilateralism and protectionism under the Donald Trump administration, the growing dependence on China as an economic partner and competitor, problems with the supply of medical equipment during the COVID-19 pandemic, and most recently the Russian invasion of Ukraine have all strengthened the quest for strategic autonomy in the EU. Such strategic autonomy entails having the ability to act and cooperate with international and regional partners wherever possible, while being able to operate autonomously when necessary. It is not limited to defence and security issues but includes also trade and industrial policies with the objective to reduce dependencies, as well as to protect Europe against economic coercion and unfair trade practices by non-EU countries. Hence trade policy has not only the objective to acquire better access for European companies to foreign markets but is also an instrument to diversify sources of supply to Europe. Latin America plays a part in this.

To allay fears that strategic autonomy could lead to more EU protectionism and would result in a more inward-looking and protectionist EU, the broader concept of “open strategic autonomy” was introduced. With the addition of “openness,” the EU signals that it will not go alone (with the objective of strengthening its resilience). Rather, it is favouring here open trade (as a source of European wealth) and is interested in managing (not downsizing) economic interdependencies and advancing its values and standards (for example human rights, environmental and digital standards) by promoting stable rules in a multilateral system of global (economic) governance. Free trade agreements (FTAs) are a tool to demonstrate EU openness. But there might be a tension between the “open” and “autonomous” aspects of the concept, for example when it comes to state aid as part of the EU’s industrial policy to address strategic dependencies.

While the EU strives to secure its strategic autonomy, Latin America is seeking to reposition itself in international politics – albeit with the handicap that it is internally fragmented, and its regional organisations and forums are weak. In Latin America, there is debate on the concept of “active non-alignment” (ANA). Originally conceived with a view to the conflict between the US and China, the positioning in the Ukraine conflict is now also being assessed from this perspective. ANA seems to be increasingly echoed in the foreign policies of Latin American governments. This approach refuses to align automatically with one or another of the major powers but does not exclude taking a stance on certain international issues. It means that Latin American governments will take foreign policy decisions mainly based on their own national interests.

A common position among the Latin American states with regards to ANA is unlikely; their political perspectives on international issues are too far apart, as shown most recently by their stance regarding the war on Ukraine or human rights violations in Nicaragua.However, individual governments may take such a position. For other governments, the option does not exist due to political or economic dependencies or political-ideological affinities with external powers.

When presenting the ANA concept, the authors (Fortín, Heine, and Ominami 2020) argued that Latin America and Europe have a common interest in creating a space of active non-alignment to avoid being drawn into the confrontations between the world’s superpowers. This may well have made some sense regarding China at the time. However, after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, China’s support of Russia, and Europe’s need for US military backing, the parameters have shifted. What appears to be a question of choice from a Latin American perspective – how to position oneself in the Ukraine conflict and vis-à-vis Russia – for Europe is one of necessity – namely, defending oneself against a genuine military threat and attack on core European values.

It will not be easy to (re)build a strategic partnership between Latin America and Europe in the new international context that has recently taken shape. Both regions have diverged in terms of respective interests. But there may be points of overlap between open strategic autonomy and active non-alignment. As Borrell argues:

On both sides of the Atlantic, we intend to strengthen our strategic autonomy and improve our economic resilience by reducing excessive dependencies. (Borrell 2022b)

Now that the state is playing a more active role in EU industrial policy and the EU is willing to protect strategic industries and reduce economic dependencies, it may be easier to come to terms with Latin American demands to reduce dependencies and protect important industries.

But from a Latin American perspective, there is also a risk of reproducing a traditional asymmetrical relationship. In an opinion piece published in several Latin American newspapers ahead of the CELAC–EU meeting in Buenos Aires, Borrell stated that:

Latin America and the Caribbean represents a global power in terms biodiversity, renewable energies, agricultural production and strategic raw materials. […] Europe has the technological and investment capacity, and it also needs alliances with reliable partners to diversify its supply chains. (Borrell 2022a)

This sounds very much like the traditional division of labour between Europe and Latin America.

European Soft Power in LAC

In news coverage inside and outside Latin America, it sometimes seems that Europe has lost all appeal except as a tourist destination. But a survey conducted in September 2021 in ten Latin American countries (Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Mexico, Uruguay, and Venezuela) by Latinobarometro (commissioned by the Friedrich Ebert Foundation and Nueva Sociedad) on regional perceptions of Europe and the EU reveals some interesting – and from a European perspective encouraging – results. When asked which world region their country would benefit most from having links with, 48 per cent named Europe, 19 per cent North America, 12 per cent Latin America, and 8 per cent Asia-Pacific.

Some 68 per cent rated relations between their country and the EU as good or very good. European countries such as France, Germany, Spain, and Sweden are still seen as models for development. Asked whether they consider European integration to serve as a model for Latin America, 60 per cent of respondents in South America (69 per cent in Mexico and Central America) said that it is useful or a model to follow (22 per cent / 19 per cent “somewhat useful”). Latin Americans recognise Europe’s leadership in domains such as the environment, human rights, peace, poverty and inequality, and humanitarian aid. But Europe is perceived as less influential or even weak when it comes to science and education, military power, as well as technological development. Europe’s economic power in Latin America is perceived as much lower than that of China or the US.

European Economic Power in LAC

From a European perspective, LAC is not a key trading partner. Brazil (rank 11) and Mexico (rank 13) accounted for 1.6 and 1.4 per cent respectively of EU foreign trade in 2021. Chile ranked 38 (0.4 per cent), Argentina 39 (0.4 per cent), Colombia 47 (0.3 per cent), and Peru 49 (0.2 per cent) (EUROSTAT). Viewed from the other side of the Atlantic, at the beginning of the twenty-first century the EU was still LAC’s second-most important trading partner (behind the US); in some countries, even the most important one. In the 2010s, the EU was overtaken by China, which has now become the leading trading partner (in goods) for many LAC countries. Only Cuba has the EU as its foremost trading partner, clearly outdistancing China here. Within the Mercosur, the EU’s share as trading partner is still higher than that of the US.

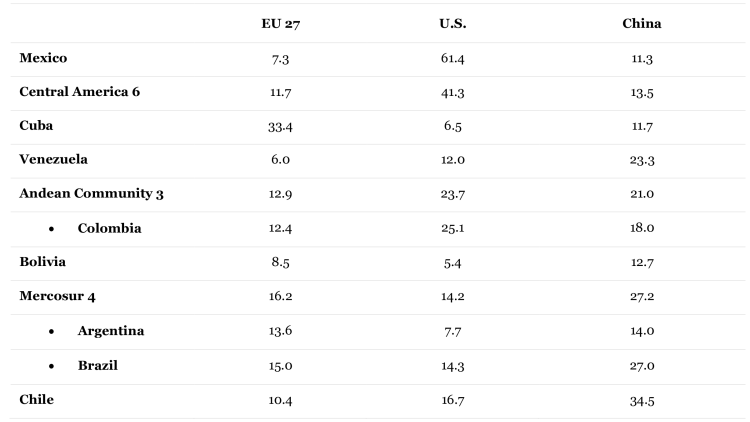

Table 1. Top LAC Trading Partners (Export and Import of Goods) in 2021

Source: Author’s compilation based on data of the EU Commission Directorate-General for Trade.

Note: Participation in total LAC trade is by country and subgroup, in %.

To complete the picture, trade in services must also be included. Not least because such trade between the EU and LAC has become more dynamic than that in goods. Between 2005 and 2019, trade in services grew by an average of 23 per cent annually compared to 5 per cent for trade in goods (Estevadeordal 2021: 28). In 2020, the EU’s participation in LAC’s service imports was 31.2 per cent (exports 19.7 per cent) (Gayá 2022).

While China has displaced Europe as LAC’s second-most important trading partner, Europe still holds the upper hand as an investor in LAC. It should be mentioned that at the end of 2020 Brazil (3.1 per cent) and Mexico (2 per cent) together absorbed more of the total foreign direct investment (FDI) stocks held by the EU in the rest of the world (EUR 2.090 billion) than China (2.3 per cent) and Russia (3.3 per cent) (EUROSTAT).In the five years before the pandemic (2015–2019), the EU (not including the Netherlands and Luxembourg, 21 per cent) accounted for 24 per cent of FDI inflows in LAC (11 countries, not including the MERCOSUR members Argentina, Paraguay, and Uruguay), the US for 25 per cent (ECLAC 2021). The EU’s share was 26 per cent in 2021 (US 35 per cent; Netherlands and Luxembourg 10 per cent) (ECLAC 2022).In the case of investments from the Netherlands and Luxembourg, the ultimate origins cannot be identified. Taking advantage of tax benefits, transnational companies (including Chinese ones) often channel their investments through these EU countries. In 2021 US companies were leading when it comes to new or greenfield investments, then followed by EU ones. In contrast, after peaking in 2019 before the COVID-19 pandemic new Chinese greenfield FDI decreased significantly in 2020 and 2021, falling behind the US, Spain, Germany, and Canada (Albright, Ray, and Liu 2022). In many LAC economic sectors, from an EU perspective competition from US companies may be stronger than from Chinese ones.

Strategic Partnership and Free Trade Agreements: A Credibility Gap

At the first Latin American-European Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1999, the goal of developing a “strategic partnership” was announced. Since then, the term has appeared again and again in official declarations.Most recently, Borrell (2022b) even spoke of a “strategic alliance” with regards to the pending EU-Mercosur associational agreement.While it is one thing to talk about strategic partnerships, it is something else entirely to actually implement them and act strategically. This is where the EU reveals certain shortcomings.

For example, the “Association Agreement with Central America” was signed in 2012 but has only been provisionally applied since 2013 for the trade part, because Belgium has not ratified the agreement. In the case of the comprehensive agreement with members of the Andean Community, Belgium has not ratified the agreement with Colombia, Peru (both signed in 2013), and Ecuador (signed in 2017); Greece and Luxembourg have still to ratify the agreement with Ecuador. The agreement is therefore only provisionally applied. The “Economic Partnership Agreement” with the CARIFORUM was approved by European Parliament in 2009 and provisional applied but has still not been ratified by Hungary. The latter is also blocking the post-Cotonou agreement between the EU and 79 African, Caribbean, and Pacific states, even though negotiations concluded in April 2021.

In her State of the Union Address on 14 September 2022, President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen declared that:

We need to update our links to reliable countries and key growth regions. And for this reason, I intend to put forward for ratification the agreements with Chile, Mexico, and New Zealand.

There has been progress – albeit slow – in modernising the agreements with Chile and Mexico. An agreement in principle was already reached with Mexico in April 2018 on the modernisation of the trade part of the 1997 “EU-Mexico Global Agreement” (supplemented by an agreement on public procurement at the subnational level in April 2020). However, as of early 2023, the Agreement has still not been signed.

In the case of Chile, the negotiation process for the modernisation of the “EU-Chile Association Agreement” (signed in 2002) started in 2017 and technically concluded in October 2021. But it took until 9 December 2022 for the negotiations to be officially concluded. Optimistic calculations assume that the legal verification and the translation of the text will be finished in six to nine months and the “Advanced Framework Agreement” with Chile can be signed in autumn 2023.It would then be the first of the outstanding agreements with Latin America to be fully realised.

The EU-Mercosur Agreement: Lula da Silva as Game-Changer?

While the agreements with Mexico and Chile are in the home stretch regarding modernisation, little has happened regarding the EU-Mercosur associational agreement since negotiations concluded in June 2019. Remarkably, von der Leyen did not mention this EU-Mercosur agreement in her State of the Union Address. In Europe, a unique coalition formed against the agreement, which includes the agricultural lobby (especially the livestock sector) and allied centre-right parties, but also fundamental opponents of globalisation as well as environmental activists and green parties.But governments (and some parliaments) had also positioned themselves against the agreement, especially the French under President Emmanuel Macron. To opponents of the agreement, President Bolsonaro’s ascent to office was a stroke of luck. His disregard for environmental policies and the fires in the Amazon rainforest mobilised public opinion in Europe, allowing agricultural lobbyists to hide their protectionist goals behind purported environmental concerns.With Lula’s election victory and his declaration of intent to protect the environment and the Amazon rainforest, this line of argument is coming under pressure.

In Europe, the main issue will be to persuade the French government (and a majority of the French National Assembly) to change course. But other European governments also need to clarify their position. The road from the declaration of a strategic interest in Latin America by the EU through the implementation of it by the latter’s member states is long and rocky. For too long, instead of using geopolitics to realise strategic autonomy and partnerships certain key actors within the EU pursued a morally dressed up protectionism.

On the Brazilian side, there is also a need for clarification. The willingness to do more to protect the environment and the Amazon rainforest is credible. With the appointment of Marina Silva as environment minister and Sônia Guajajara as head of Brazil’s new Ministry of Indigenous Affairs, Lula’s announcements have gained in stature. Silva also participated in the World Economic Forum in Davos in January 2023, reiterating the commitment of the Lula administration to net-zero deforestation by 2030. However, political announcements must prevail in practice in the face of resistance from a rather conservative Brazilian Congress with a strong agricultural lobby.

Lula’s position on the EU-Mercosur agreement also needs specification. In a press conference on 22 August 2022, he expressed rather ambivalent views hereon. While saying that he wants an agreement between Mercosur and the EU, he also declared that “Brazil is not obliged to accept an agreement that does not respect what Brazil needs” (Pérez Bella 2022). Lula argued that the trade agreement does not promote Brazil’s reindustrialisation. In his first speech after winning the elections on 30 October, Lula declared:

We want fairer international trade. […] We are not interested in trade agreements that condemn our country to the eternal role of exporter of commodities and raw materials. (g1.globo 2022)

His former foreign minister Celso Amorim argued in a similar manner (Lirio 2022), contending (like Lula) that Brazil cannot renounce a privileged position for local companies in the case of government procurements.However, during a state visit to Uruguay, speaking only a day after the CELAC summit in Buenos Aires, President Lula declared the signature of the EU-Mercosur agreement to be both urgent and necessary. Moreover, he remarked that possible future free trade negotiations between Mercosur and China were conditional on the prior signing of this agreement with the EU.

From a European perspective, there seem to be two realistic ways to safeguard the EU-Mercosur agreement (Voituriezet al. 2022): a joint declaration clarifying the commitments of the “Trade and Sustainable Development” (TSD) chapter or a binding additional protocol. In contrast to the first option, the latter could add TSD commitments to the existing ones in the draft EU-Mercosur agreement. It is possible that the Mercosur countries will agree to this, but they will demand a quid pro quo regarding public procurement and the protection (for example by extending the transition period) for certain industries.

The big challenge is to find a balance between the interests of both sides without renegotiating the text of the agreement per se. Doing so would require a new mandate for the EU Commission, and, after more than 20 years of negotiations, would delay the conclusion of an EU-Mercosur agreement far into the future. As Borrell rightly points out: “The tango might say that 20 years is nothing, but in this case, it is too long” (Borrell 2022b). Ultimately, it might be better for the EU not to touch the agreement, and to rely on the new Brazilian government’s promises to protect the environment and the Amazon rainforest. Moreover, instead of unilaterally imposing conditions on Latin America, for example regarding environmental protection and the fight against climate change, the EU should provide increased support for regional initiatives, such as the Leticia Pact or the Escazú Agreement.

2023: A Window of Opportunity

Whether 2023 will be the year of Latin America in Europe and vice versa remains to be seen. Geopolitical worldviews in Europe and Latin America have come to diverge. Bi-regional summits (and other bi-regional meetings) between CELAC and the EU can contribute to improved mutual understanding and, where appropriate, to a convergence of positions on key international issues. But Europe cannot expect preferential treatment from Latin America, where most governments want to differentiate and equilibrate their foreign relations as far as possible. But the EU also has room for manoeuvre. From a European perspective, it is better to rely on serious, substantive strategic partnerships – if necessary, with a few select partners – than on grand joint declarations that set aside principles and have no practical consequences.

Latin America can become an important strategic partner for the economic transformations that the “European Green Deal”aspires to. Formal strategic partnerships exist with Brazil and Mexico, ones needing to be revived. The EU remains an important player in Latin America as a trading partner and investor (through European companies), and given that it has soft power or power of attraction. But in a multipolar world, the EU must position itself more strongly as one of the poles and better emphasise its economic power (resources).Since China has created new dependencies in Latin America, the EU should try to position itself as a counterweight hereto. However, for this Europe must also offer material incentives. Just talking about shared values will not be enough. The EU must learn to promote its geopolitical goals in a world where the geo-economic parameters are shifting to its disadvantage.

In response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Borrell had spoken of the birth of a geopolitical Europe. Now it is also necessary to act from a geopolitical perspective vis-à-vis Latin America. The year ahead may be the last chance for the EU-Mercosur associational agreement. Considering the experience with other agreements with Latin American countries and regional organisations, the EU-Mercosur agreement should be provisionally applied in those parts falling under EU competence once the European Parliament has ratified it. This and other agreements with Latin America must be presented to the political public in Europe less as FTAs than as agreements to secure Europe’s open strategic autonomy.

Footnotes

References

Albright, Zara C., Rebecca Ray, and Yudong Liu (2022), China-Latin America and the Caribbean Economic Bulletin, 2022 Edition, Boston University, accessed 27 January 2023.

Borrell, Josep (2022a), Re-Launching the Partnership between the EU and Latin America and the Caribbean, 28 October, accessed 25 January 2023.

Borrell, Josep (2022b), Why Europe and Latin America Need Each Other, 30 November, accessed 25 January 2023.

ECLAC (Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean) (2022), Foreign Direct Investment in Latin America and the Caribbean, 2022 (LC/PUB.2022/12-P), Santiago de Chile: ECLAC.

ECLAC (Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean) (2021), Foreign Direct Investment in Latin America and the Caribbean, 2021 (LC/PUB.2021/8-P), Santiago de Chile: ECLAC.

Estevadeordal, Antoni (2021), Geopolitics and Trade: Future Relations between the European Union and Latin America and the Caribbean, in: Patricia García-Durán Huet and Eloi Serrano Robles (eds), Geopolitics and Trade in Changing Times, Barcelona: CIDOB, 27–33.

Fortín, Carlos, Jorge Heine, and Carlos Ominami (2020), El no alineamiento activo: un camino para América Latina, Nueva Sociedad, Opinión September, accessed 27 January 2023.

FES, NUSO, and Latinobarometro (2022), What are Latin America’s Perceptions on the European Union?, accessed 25 January 2023.

g1.globo (2022), Leia e veja a íntegra dos discursos de Lula após vitória nas eleições, 31 October, accessed 25 January 2023.

Gayá, Romina (2022), EU-LAC Trade in Services, 28 October, accessed 25 January 2023.

Lirio, Sergio (2022), América del Sur en la nueva geopolítica global. Entrevista a Celso Amorim, Nueva Sociedad 301, Septiembre–Octubre, accessed 27 January 2023.

Mijares, Victor (2022), The War in Ukraine and Latin America: Reluctant Support, GIGA Focus Latin America, 2, accessed 27 January 2023.

Nolte, Detlef (2021), The EU’s Beef with Mercosur: Geo-Economics Versus Climate Diplomacy, Latin America’s Environmental Policies in Global Perspective, Washington, DC: Wilson Center.

Pérez Bella, Manuel (2022), Lula quiere reabrir las negociaciones del acuerdo Mercosur-Unión Europea, EuroEFE, 22 August, accessed 26 January 2023.

Voituriez, Tancrède, Klaudija Cremers, André Guimaraes, Paulo Moutinho, and Olivia Zerbini Benin (2022), Lula’s Election: A Blessing for a Green EU-Mercosur Association Agreement?, IDDRI Policy Brief, 9, November, accessed 27 January 2023.

Editor GIGA Focus Latin America

Editorial Department GIGA Focus Latin America

Regional Institutes

Research Programmes

How to cite this article

Nolte, Detlef (2023), The European Union and Latin America: Renewing the Partnership after Drifting Apart, GIGA Focus Latin America, 2, Hamburg: German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), https://doi.org/10.57671/gfla-23022

Imprint

The GIGA Focus is an Open Access publication and can be read on the Internet and downloaded free of charge at www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publications/giga-focus. According to the conditions of the Creative-Commons license Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0, this publication may be freely duplicated, circulated, and made accessible to the public. The particular conditions include the correct indication of the initial publication as GIGA Focus and no changes in or abbreviation of texts.

The German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) – Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien in Hamburg publishes the Focus series on Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and global issues. The GIGA Focus is edited and published by the GIGA. The views and opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the institute. Authors alone are responsible for the content of their articles. GIGA and the authors cannot be held liable for any errors and omissions, or for any consequences arising from the use of the information provided.