- Home

- Publications

- GIGA Focus

- Growing Sino–US Rivalry in Latin America: An Opportunity for the EU

GIGA Focus Latin America

Growing Sino–US Rivalry in Latin America: An Opportunity for the EU

Number 5 | 2023 | ISSN: 1862-3573

In Latin America and the Caribbean, China’s growing presence represents a significant challenge to the worn-out hegemony of the US. Characterised by its diversity and an ardent desire to preserve national autonomy, the region finds itself at a crucial turning point. The EU faces both risks of marginalisation and unique opportunities to forge alliances based on mutual respect and shared values.

China’s advance in Latin America has challenged traditional US influence, significantly altering the geopolitical and economic balance in the region.

Latin America’s geopolitical loyalties and priorities are not homogeneous; diversity and the search for national autonomy are crucial to understanding regional dynamics.

The EU must recognise the risks of further isolation due to the growing influence of China and the US, in actively seek opportunities to establish more meaningful and varied alliances.

The EU should take advantage of its cultural influence and its commitment to environmental sustainability to position itself as a viable and desirable alternative to the dominant powers.

Policy Implications

The competition between China and the US in Latin America and the Caribbean provides the EU with a rare opportunity to redefine its role. By focusing on respect for diversity and national autonomy alongside strengthening its soft-power capabilities, the EU can establish a more influential and positive presence in a region in transformation.

Evaluating China’s Advances in Latin America and the Caribbean

The history of Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) has been intimately linked to that of US influence, a role manifesting itself through a variety of political, economic, and cultural channels. From the “Monroe Doctrine” in the nineteenth century to complex interactions in the era of globalisation, the US presence has dramatically shaped the geopolitical landscape of the region. This legacy, well-documented and widely recognised, includes both periods of cooperation and development and episodes of interventionism and ideological conflict. Given that Washington’s role in LAC is widely known and has been the subject of numerous analyses, focus must turn instead to assessing China’s recent advances in the region during a period running from 2001 to 2023. This is worth dividing into three specific subperiods: 2001–2007; 2008–2014; and 2015–2023. How Beijing’s growing influence is helping reconfigure the geopolitical and economic balance in this dynamic context can hereby be grasped, as marking a change in direction for regional alliances and priorities.

Since Xi Jinping came to power in 2013, China has made significant advances in LAC in both the geoeconomic and diplomatic spheres. These developments reflect a well-articulated strategy to increase its influence in a region traditionally aligned with the West. China has, accordingly, strengthened its ties with countries such as Argentina, Brazil, Ecuador, El Salvador, and Nicaragua, becoming a crucial trading partner for the region (South China Morning Post 2023). In 2022, Latin America exported approximately USD 184 billion and imported USD 265 billion in goods to and from China according to the Global Development Policy Center (2023) at Boston University. Significant examples of China’s growing economic presence in LAC include the free trade agreement (FTA) with Ecuador and the multiple agreements with Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Ecuador, and Venezuela in areas such as satellite development and the digital economy (Frenkel and Blinder 2020; Mijares and Chenou 2023; South China Morning Post 2023). In terms of loans, the China Development Bank and the Export-Import Bank of China have historically been the largest lenders in the region, although the practice has declined in recent years. In 2022, however, there was a rebound here, with new financial commitments in Barbados, Brazil, and Guyana, totalling USD 813 million in loans (Global Development Policy Center 2022).

Politically, China has stepped up efforts to gain recognition of its sovereignty over Taiwan. Since 2017, five LAC governments have established diplomatic relations with China, ending their previous formal recognition of Taiwan. The most recent case was Honduras in March 2023 (The Diplomat 2023; USNI News 2023). China has used its role in organisations such as CELAC (Comunidad de Estatos Latinoamericanos y Caribeños) to foster collaboration and support in the region, highlighting its focus on regional integration and South–South cooperation (USNI News 2023). In that sense, the “3rd Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation,” held in Beijing in October, marked a significant milestone in China’s relationship with LAC. This event, which commemorated the tenth anniversary of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), saw the participation of several LAC leaders, reflecting the growing importance of the region in China’s global strategy (Prensa Latina 2023). During the Forum, the elevation of Colombia’s status in its bilateral relations with China was highlighted, becoming a “Strategic Partner.” This move is significant, considering that Colombia is one of the closest US allies in Latin America and NATO’s only “Global Partner” in the region – further to being a “major non-NATO ally” of the US. However, it is essential to note that Colombia has not yet joined the BRI (Reuters 2023).

Another relevant aspect of the Forum was the meeting between Xi and Nicolás Maduro, President of Venezuela, in which they agreed to elevate the latter country’s status in bilateral relations to “All-Weather Strategic Partner” – a designation reserved only for select diplomatic partners of China. Maduro has cultivated close relations with China during his years in power, securing support for his country in the form of loans, cash, and investments worth tens of billions of US dollars. China is Venezuela’s largest creditor, having lent it approximately US 67 billion in the 2010s; the Latin American country is repaying this debt with oil shipments (Al Jazeera 2023).

Thus, China has adopted a multidimensional approach to LAC that combines active diplomacy, economic participation, and strategic alliances. Through these efforts, China has not only reconfigured its economic relations in the LAC region but also achieved a significant change in the wider diplomatic landscape, challenging the traditional influence of the West there. However, such efforts do not always produce the desired results. In fact, when the way in which LAC states vote in the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) is reviewed in detail, it becomes evident that evaluations of Chinese political progress in the region could be overestimated.

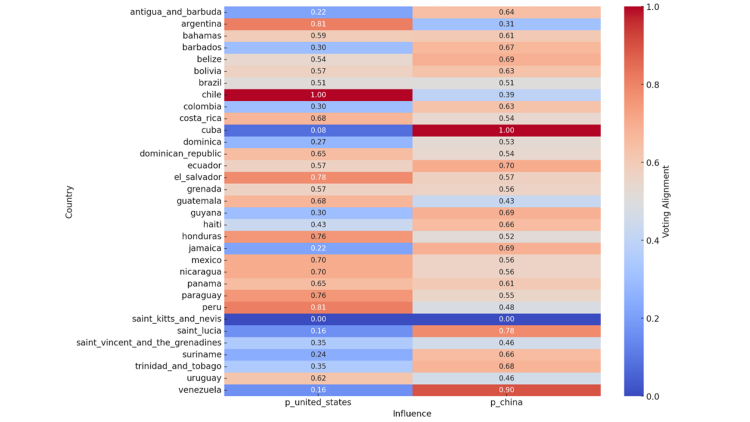

Thus, when all UNGA resolutions appearing under the labels “human rights” or “international security” are reviewed, the results appear poorly aligned with China’s LAC policy. In fact, there is a clear tendency for the region, in general, to vote more in line with China’s positions than the US’s (see Figure 1 below). Nevertheless, there are at least three phenomena worthy of comment here: first, how LAC voted closer to China’s stances than the US’s even before Beijing adopted an assertive policy towards the region. In the period 2001–2007, these countries thus voted together 68 per cent of the time in a manner identical to China. That is, when it came to matters of human rights and/or international security, more than two-thirds of the time they voted “Yes,” “No,” “Abstain,” or “No-Vote” along with China.

In contrast, only 17 per cent did so together with Washington. This looks impressive, mainly since it includes the first phase of the US “War on Terror.” However, this turn of events must be qualified because it was informed by more than political alignment with China regarding Beijing’s “Third World” voting tendency. Along with this went also LAC’s inclination not to align strongly with the US and the splendour phase of leftist governments in the region, who enjoyed high prices for raw materials – and, therefore, broad autonomy.

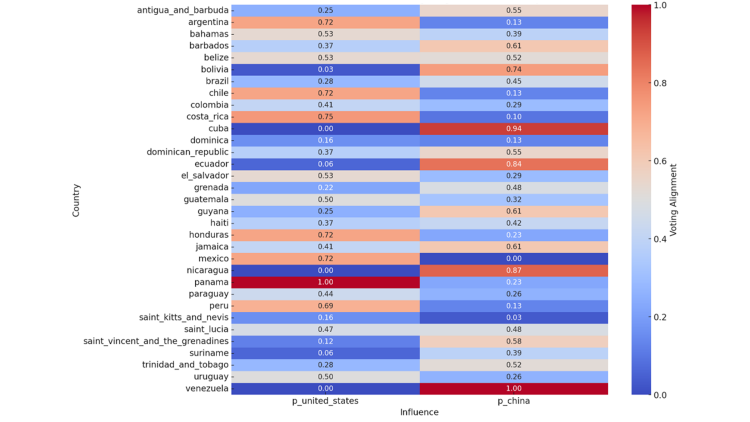

The same data reveal, second, something else of great importance: namely, that the period 2008–2014 (Figure 2) – the peak of Chinese capital and influence permeating most of the LAC region – was the lowest moment of diplomatic alignment at the UNGA. But, in addition, it was also a time of greater cohesion in the LAC vote (standard deviation of 0.081), being higher than that of the first examined time period, 2001–2007 (0.122). However, that cohesion dissipates in the third examined time period, 2015–2023 (0.138) – which suggests more national than collective strategies in terms of foreign policy and preferences between East and West.

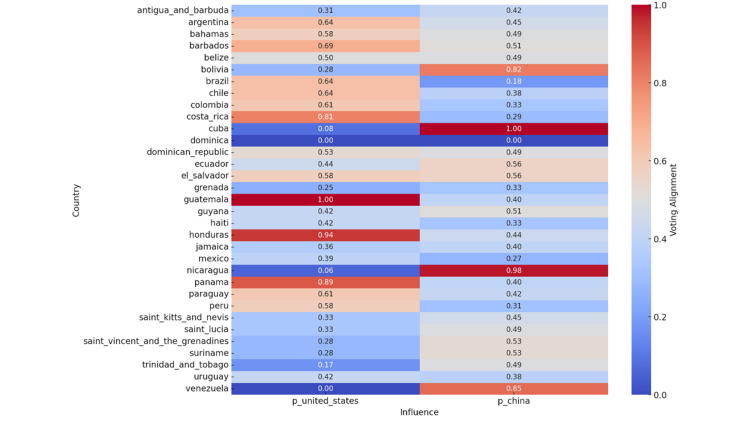

The third and final striking phenomenon here is the relative drop in the vote correlation between LAC and China towards the last observed period, 2015–2023 (Figure 3). UNGA vote alignment here has fallen below 60 per cent, while that with the US has since reached almost 30 per cent. This is occurring despite the consolidation of China’s financial and commercial penetration in the region and circumstances encompassing all the splendour of Xi’s government. Nevertheless, it has also been a moment of reversal for Latin American leftist governments, at least for most of this third time period.

Between Autonomy and Alignment

How do the LAC countries manage their autonomy in a global setting dominated by great powers? A delicate balance exists between independence, geopolitical influence, and pragmatism at the UNGA when it comes to LAC foreign policy. Voting patterns indicate complex negotiation between the search for autonomy, the influence of great powers, and the internal dynamics of each country. Autonomy is associated with the ability of states to maintain their independence and promote their national interests within the global system. However, another school of thought suggests that interdependence between states can both diminish the autonomy of key actors and offer peripheral countries some limited autonomy through integration into the globalised economy. In this sense, autonomy becomes a relative phenomenon, one subject to fluctuations in international politics and economics.

Autonomy in LAC foreign policy has also been discussed from perspectives such as dependency, where it is considered a result of unequal economic structures and power relations. Specialised studies highlight how local elites can rationalise their lack of autonomy and seek less subordinate forms of insertion in world politics. This vision is reflected in the pragmatic and often reactive stance of many LAC countries at the UNGA, where they seek to balance external demands with their own national and regional agendas. There, the votes reflect not only a fight for autonomy in the classical sense but also an exercise in strategic adaptation and search for opportunities within a complex international system. Through their voting patterns, the LAC countries thus demonstrate a pragmatic and adaptive approach to foreign policy, attempting to maximise their respective influence and benefits in a challenging global environment.

Figure 1. Period 1 (2001–2007)

Source: Author’s own elaboration, based on UN data (2023).

Figure 2. Period 2 (2008–2014)

Source: Author’s own elaboration, based on UN data (2023).

Figure 3. Period 3 (2015–2023)

Source: Author’s own elaboration, based on UN data (2023).

Indeed, the data from the exact voting heatmaps shows three different and differentiated moments in LAC states’ relations with the two great powers, China and the US. These reflect external and internal tensions, ranging from on economic needs to ideological preferences and as fluctuating greatly in the early twenty-first century. Nevertheless, we cannot lose sight of the fact that autonomy, which can be understood in maximalist or minimalist terms, is the strategic substrate that lies at the heart of regional decision-making processes. This is due to the co-education of these states, the types of ideology that they have developed due to their peripheral histories, but also due to the regional socialisation leading leaders to demonstrate that they must conduct themselves with autonomy with respect to the great powers.

Thus, understanding LAC foreign policy behaviour is no trivial matter. We have already seen that growing economic ties with China do not always reflect the latter’s expected regional influence; the variability and diversity of a setting made up of more than 30 sovereign states is also evident. That is why, to facilitate examination of regional policy, it is important to have approriate analytical tools – such as a classification mechanism that identifies navigable categories. Here, the classification of LAC countries based on their alignment with the great powers seeks to provide a clearer and more nuanced understanding of foreign policy. This classification scheme helps highlight also autonomy, strategic balancing, and policy shifts, underscoring the complexity and multifaceted nature of international relations in the region.

Diversity and Flexibility in Alliances

Based on the presented data for the three time periods and the complexity inherent to LAC’s international relations, a review and expansion of the categories of alignment is required to reflect in a more nuanced way the dynamics at play here. These revised categories will allow for a better understanding of both regional trends and external influences.

Leaning towards China: Countries in this category have shown extensive vote alignment with China at the UNGA. This alignment may reflect a deepening economic and political relationship with China, especially in the context of the latter’s growing influence in LAC. In many cases, this relationship manifests itself in significant trade agreements, investment in infrastructure, and a diplomatic stance closer to Chinese positions on international issues. However, this alignment may also indicate a dependence on China, especially in countries where it is a key trading partner or a major investor in critical sectors.

Leaning towards the US: Countries in this category tend to align with the US, as often reflective of historical, economic, and security ties. US influence in LAC has been constant, although it has fluctuated in intensity over the years. Countries that lean towards the US might have FTAs with it, receive security assistance, or be traditional allies in political and military matters. This alignment may also be influenced by domestic politics, where pro-Western governments seek to maintain close relations with Washington.

Consistently Strategic Balancers: These countries have adopted a more balanced approach, attempting to maximise the benefits of relations with both China and the US. Their foreign policy is pragmatic in seeking cooperation with both powers without leaning significantly towards one particular side. This approach can be part of a broader strategy to maintain sovereignty and autonomy in foreign policy, taking advantage of the economic and political opportunities offered by both China and the US.

Mobile and Autonomous: Countries in this category show a variable voting pattern at the UNGA, with no consistent tilt towards any of the great powers. This behaviour reflects a more autonomous and adaptive foreign policy influenced by domestic considerations and a willingness to act independently on the global stage. These countries may be seeking to diversify their international relations and adopt positions that speak to a mix of national, regional, and global interests.

Transitional: Countries classified as transitional have experienced notable changes in their alignment during the different time periods analysed. This may reflect transformations in domestic politics, such as in government or in foreign policy. Shifts may also be the result of fluctuations in international relations or responses to global and regional events. This category highlights the dynamic and changing nature of LAC foreign policy.

Figure 4. LAC Countries’ UNGA Voting Behaviour regarding China and the US, 2001–2023

Source: Author’s own elaboration, based on UN data (2023).

Of course, this classification scheme is still generalised since there are notable differences even between members of the same category. Furthermore, the categories capture well the overall behaviour of each LAC country during the period 2001–2023 but not always the most recent political fluctuations therein. Despite these shortcomings, the categories allow us to see a diverse and complex mapping of positions in which geographical proximity does not always explain external behaviour. This map is essential in the political analysis of short-term LAC decisions, as it allows us to make an initial approximation of what game, generally speaking, each state of the region wants to play.

Domestic Polarisation and Geopolitical Opportunities

In geoeconomic and geopolitical terms, a delicate balance is observed in LAC between the growing influence of China and the historical dominance of the US. Although this dynamic may seem an obstacle to the EU’s greater regional involvement, it also presents opportunities since it is evident that LAC foreign policy is a complex patchwork of pursuing autonomy, strategic alignment, and tactical adaptation. Voting patterns at the UNGA serve as a prism through which to observe how these countries skillfully balance external influences with their national and regional agendas. This complex panorama reminds us that we cannot fully rely on economic patterns in seeking to define the contours of alignment with the great powers. Other forces are operating both on the inside and outside of these states, even from within the minds of respective leaders. It is, therefore, crucial to remember that this relative autonomy and strategic power play not only outline the nature of LAC’s relationship with the great powers but also open pathways to new opportunities and alliances.

Geoeconomic and geopolitical interactions in the region are not limited to a simple division between Chinese and US influence. As shown, it is a much more nuanced spectrum seeing significant variation from country to country. Each state, depending on its own political, economic, and historical circumstances, leans to varying degrees towards one side or the other or even seeks to balance between both. Thus, the US has historically been the dominant actor in the region, exerting its influence through diplomacy, economic aid, trade agreements, and, in some cases, direct intervention. However, this influence has been subject to criticism and rejection at various times and in different places – especially in nations that have sought greater autonomy and wished to challenge US hegemony. China, for its part, has emerged as a vital economic and political partner for many LAC countries in recent decades. Its focus has been primarily on economic affairs, focusing as such on investments, loans, and trade. However, China’s growing regional presence has also raised concerns, particularly around issues such as economic dependence, environmental sustainability, and investment transparency.

Opportunities for the EU

In this context, the EU has a unique opportunity to position itself more prominently in the LAC region. Traditionally perceived as a secondary player compared to the US and China, the EU can offer an attractive alternative based on taking a more balanced approach that respects the autonomy and specific needs of each LAC country. Unlike the often-perceived dominant or even neocolonial influence of the US’s and China’s pragmatic, trade-focused approach, the EU can present a model of cooperation based on shared values, mutual respect, and sustainable development. With its strong traditions of human rights, democratic governance, and commitment to multilateralism and environmental sustainability, the EU can offer forms of collaboration that more closely align with the aspirations of many LAC countries. Additionally, it can capitalise on its history in and cultural ties to the region – especially in those countries with European linguistic and cultural heritages – in seeking to strengthen relations.

Competition between the US and China should, therefore, not be seen exclusively as an obstacle for the EU but as a catalyst to rethink and therewith strengthen its role in LAC. By positioning itself as a partner that understands and respects the complexity and diversity of the region, EU states can find fertile ground to build deeper and more meaningful relationships of benefit to both LAC and Europe alike. For example, the cultural and educational soft power of the EU in LAC is a tool as powerful as it is underestimated in geostrategy. Cultural and linguistic affinity, especially with those countries with Spanish and Portuguese roots, offers the EU a unique advantage in the region – one that neither the US nor China can easily match.

European universities have a special attraction for LAC students. These institutions are seen not only as centres of academic excellence but also as places where students can experience a cultural environment like their own, namely one that is less intimidating and more welcoming. Scholarships and exchange programmes offered by the EU and its member states allow LAC youth to access a high-quality education while building lasting relationships and networks in Europe. In comparison, the cultural and educational proposals of the US and China do not always resonate in the same way here. Although the US remains a popular destination among LAC youth for higher education, its cultural influence is often overshadowed by foreign policy and the perception of a dominant culture. China, on the other hand, despite its increasing efforts to establish cultural and educational ties, faces more significant linguistic and cultural barriers in this regard.

Additionally, the EU’s commitment to civil and political rights, as well as to environmental sustainability, presents a strategic opportunity to strengthen its presence in LAC. Marked by a history of struggles for human rights and a growing interest in environmental conservation, the region finds in the EU a partner aligned with its own values and aspirations. This is why the EU can take advantage of this affinity to establish deeper connections with the LAC nations. In a world region where challenges to freedom of expression, minority rights, and gender equality are persistent concerns, the EU can offer assistance and collaboration to help strengthen democratic institutions and the rule of law. This approach would not only resonate with the concerns of local civil society but also offer a stark contrast to the practices of China and sometimes also the US – whose policies in the region have often prioritised economic or strategic interests over the promotion of human rights.

The EU’s commitment to environmental sustainability and thus tackling climate change is another area of resonance with LAC. Home to a significant portion of the world’s biodiversity and populations disproportionately affected by climate change, this region is actively seeking sustainable solutions and partnerships on environmental conservation. The EU, a leader in renewable energy and sustainability policies, can offer expertise, technology, and financing for joint projects here. This would not only serve to address a critical need in the region but also create a clear contrast with the policies of other global players that have often favoured industrial development without sufficient consideration for its environmental impacts.

Thus, the EU can capitalise on these shared interests and values to build alliances with both governmental and non-governmental actors in the region. This includes working with local human rights organisations, environmental advocacy groups, and progressive governments that value democracy and sustainability. More effective cooperation and greater popular support for the EU’s presence in the region would ensue. In contrast to China’s influence, focused as it is on economic investment and infrastructure, and the US’s historically complex presence in the region, the EU can position itself as a partner that prioritises well-being and sustainable progress. This would give the EU a distinct advantage on the geopolitical stage, opening the door for more significant and lasting influence in the region.

Finally, political polarisation is a phenomenon that cannot be ignored in the analysis of EU–LAC relations. This is not merely a matter of internal divisions but also reflects global trends vis-à-vis alignment with the great powers, oscillating between a pro-Western orientation and a tilt towards competitors such as China and other Eurasian powers. The EU must understand that this political polarisation represents, in fact, a significant opportunity. The variety of governments and policies to be found in the region, from radical left-wing governments to conservative and libertarian right-wing administrations, offers a wide spectrum of possibilities for diplomacy and cooperation. The EU, with its history of negotiation and diverse political engagement, is well-positioned to engage with this plurality of political actors.

Despite potential ideological differences, there is still considerable room for dialogue and cooperation between the EU and the LAC governments. This need not be limited to alliances with those sharing a similar ideology to oneself. Even governments that may seem ideologically distant from European values may still have common interests in areas such as trade, investment, education, technology, and environmental protection. There have been missed opportunities with pro-Western movements and leaders in the region. These groups, often acting in line with left-wing policies, actively seek to strengthen ties with the West. Although the EU’s political platforms are largely based on social-democratic ideals, this should not impede the developing of relations with these actors. Recognising and supporting these groups could strengthen the European presence in the region and help offset the influence of other global actors.

Thus, the EU must not simply view relations through the prism of traditional politics. In an era when identity and cultural discourses are becoming increasingly important, the EU must seek opportunities that transcend partisan politics. This includes engaging with civil society, the business sector, and academia, creating links that are based on shared interests and values beyond political affinities.

In sum, the growing Sino–US rivalry in LAC presents both significant challenges and opportunities for the EU. As patterns of influence and alignment in the region continue to evolve, the EU must adopt a strategic and nuanced approach based on a deep understanding of local dynamics. By focusing on strengthening its soft-power capabilities and promoting a cooperation model based on mutual respect, environmental sustainability, and shared values, the EU can establish itself as a key partner in LAC. Playing such a role would not only benefit European interests but also contribute to a healthier geopolitical balance and more sustainable development in the region at large. In this complex and ever-changing landscape, the EU’s ability to adapt and respond proactively will be crucial to its wider success and relevance in a world undergoing an extensive transition of power.

The author thanks Vicente Agüero, student of Mathematical Engineering at the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile and former exchange student at the Universidad de Los Andes, for his assistance in collecting and processing the data.

Footnotes

References

Al Jazeera (2023), China’s Xi Says “Upgrading” Venezuela Relations after Meeting Maduro, 13 September, accessed 12 November 2023.

Frenkel, Alejandro, and Daniel Blinder (2020), Geopolítica y cooperación espacial: China y América del Sur, in: Desafíos, 32, 1, 1–30, 1 November 2023.

Global Development Policy Center (2023), China-Latin America and the Caribbean Economic Bulletin, 2023 Edition, accessed 12 November 2023.

Global Development Policy Center (2022), At a Crossroads: Chinese Development Finance to Latin America and the Caribbean, 2022, accessed 12 November 2023.

Mijares, Víctor M., and Jean-Marie Chenou (2023 forthcoming), China’s Technological Influence in the Andes, Potsdam: Friedrich-Naumann-Stiftung.

Prensa Latina (2023), Belt and Road Initiative Consolidates China-Latin America Cooperation, 17 October, accessed 12 November 2023.

Reuters (2023), China Upgrades Diplomatic Ties with Close US Ally Colombia, 25 October, accessed 12 November 2023.

South China Morning Post (2023), 5 Trade Moves China Has Made in 2023 in Latin America – The Traditional Backyard of the US, accessed 12 November 2023.

The Diplomat (2023), Taiwan’s Future in Latin America, 11 May, accessed 12 November 2023.

United Nations (2023), Voting Data, accessed 15 September 2023.

USNI News (2023), Report to Congress on China’s Engagement with Latin America and the Caribbean, accessed 12 November 2023.

Editor GIGA Focus Latin America

Editorial Department GIGA Focus Latin America

Regional Institutes

Research Programmes

How to cite this article

Mijares, Victor (2023), Growing Sino–US Rivalry in Latin America: An Opportunity for the EU, GIGA Focus Latin America, 5, Hamburg: German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), https://doi.org/10.57671/gfla-23052

Imprint

The GIGA Focus is an Open Access publication and can be read on the Internet and downloaded free of charge at www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publications/giga-focus. According to the conditions of the Creative-Commons license Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0, this publication may be freely duplicated, circulated, and made accessible to the public. The particular conditions include the correct indication of the initial publication as GIGA Focus and no changes in or abbreviation of texts.

The German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) – Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien in Hamburg publishes the Focus series on Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and global issues. The GIGA Focus is edited and published by the GIGA. The views and opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the institute. Authors alone are responsible for the content of their articles. GIGA and the authors cannot be held liable for any errors and omissions, or for any consequences arising from the use of the information provided.