- Startseite

- Publikationen

- GIGA Focus

- Conditions for Democratic Transitions: Venezuela’s 2024 Elections

GIGA Focus Lateinamerika

Conditions for Democratic Transitions: Venezuela’s 2024 Elections

Nummer 2 | 2024 | ISSN: 1862-3573

The resounding victory of María Corina Machado in the opposition primaries of October 2023 gave new hope for a transition from autocratic rule to democracy. But this also sounded the alarm among the Venezuelan government, whose survival depends on maintaining control over the executive. Nevertheless, current both internal and international conditions favour the Nicolás Maduro regime.

Regional opposition has waned with the arrival into office of left-wing governments in Brazil and Colombia, as well as general crises facing formerly anti-Maduro regimes like those of Ecuador and Peru. EU and US opposition has diminished due to Russia's war against the Ukraine and the Israeli-Gaza war.

When comparing current political conditions to those the last time there was an attempt to oust the Maduro government (2018–2019), it is fair to argue that the situation today is more favourable to the incumbent than it was previously.

Venezuela’s economic, security, and diplomatic circumstances are also significantly better than they were in the years 2014–2019. These include lower inflation, increased revenues, improved urban security, better control over national territory, and renewed diplomatic ties with the Latin American region and with Western powers.

The conditions for free and fair elections in Venezuela are yet to materialise, and the Maduro’s regime control over the Supreme Tribunal of Justice and the National Electoral Council only discredit the possibility of a transition to democracy being achieved via the ballot box.

Policy Implications

The opposition is already showing signs of fragmentation due to the unyielding ban on candidate Machado taking public office, while US pressure has faded after the Barbados Agreement of October 2023. Therefore, the EU’s position and diplomatic pressure might be the only way to push for better electoral conditions in Venezuela.

Finally United: María Corina Machado’s Unexpected Victory

Looking at the reaction by the Nicolás Maduro government to the resounding victory of María Corina Machado in the opposition primaries of October 2023, it is fair to assume they did not expect her to win with such an overwhelming majority, having taken 93 per cent of the vote. The opposition never previously had a presidential candidate who would gain such extensive popular support since the coming to power of “Chavismo” (see Table 1 below), which has always helped the respective incumbents stay in office. Since Maduro became president in 2013, the government has focused on creating divisions within the opposition by banning popular candidates from holding public office, changing the dates of elections, and even prohibiting its umbrella organisation from participating in the 2018 polls. This was a particularly successful approach during the latter elections, in which opposition candidate Henri Falcón and independent candidate Antonio Bertucci participated despite the opposition’s calls to boycott them.

Table 1. Opposition Leaders in Venezuela’s Presidential Elections, 2006–2024

Election Year | Unifying Opposition Candidate | Vote Percentage in Primaries |

2006 | Manuel Rosales (Governor of Zulia) | No primaries were celebrated; alternative candidates dropped out of the race |

2012 | Henrique Capriles Radonski (Governor of Miranda) | 64% of the vote |

2013 | Capriles Radonski (Governor of Miranda) | No primaries celebrated; 2012 primary results used |

2018 | No candidate (splintering) | The National Electoral Council (CNE) banned the opposition umbrella group from participating |

2024 | Machado (banned from public office) | 93% of the vote |

Source: Author’s own compilation, based on news articles regarding opposition primaries.

Machado was not a prominent candidate until recently. She has been an opposition figure since the beginning of the Chavismo years, but she only held public office between 2010 and 2014 as a member of the National Assembly of Venezuela, until she was kicked out of it by the Supreme Tribunal of Justice (TSJ). Despite being part of the opposition since the outset, she only recently resurfaced as a protagonist after the COVID-19 pandemic, playing the role of most radical anti-Chavismo candidate among the opposition. Being in constant opposition to Chavismo while maintaining distance from its delegitimised mainstream leaders – including candidates Capriles Radonski, Rosales, and Freddy Superlano – catapulted Machado into the position of being the most viable and legitimate option in the eyes of the Venezuelan population. Despite the ongoing infighting among its leaders before the primaries, the overwhelming victory of Machado served to unify the opposition behind her.

A unified opposition led by an extremely popular candidate is a situation the Maduro government had only faced once before, during the 2013 presidential elections. Even then, Capriles Radonski only obtained 60 per cent of the vote in primaries. The current circumstances are compounded by the fact that the Maduro government’s popularity is at an all-time low: according to a Delphos poll from July 2023, 85 per cent of the Venezuelan population wants him out of office.

Maduro’s Countermeasures: Weaponising the Judiciary, Delegitimisation, and Diversion

Autocratic rulers rely on a balance between repression, legitimisation, and co-optation to stabilise their regimes (Gerschewski 2013). Maduro successfully deployed all of these tools to maintain power during the turbulent protest years of 2014–2019. This included suppressing the population and arresting/banning political opponents (repression), maintaining a performative democracy while attending internationally hosted dialogues with the opposition (legitimisation), and allowing opposition leaders to access low-level government positions to splinter the Mesa de la Unidad Democrática (MUD) (co-optation).

Hugo Chávez constantly used elections as a key tool of legitimation; while he was always considered a very well-liked candidate, he abused state power and resources to maintain such popularity (Martin 2017). Maduro, on the other hand, faced with a grave economic crisis and suffering a legislative defeat in 2015, relied on repression and censorship of the opposition and disloyal army officers, while co-opting military, political, and economic elites through cronyism (Corrales 2020). This was not without its costs: constant protests and power contestation, increasing unease among the defence and security forces, and the tarnishing of Venezuela’s international image as a democratic state.

Despite the attempt of Maduro to return to Chavez’s model of legitimation through co-opted and unbalanced polls since 2021 – achieved by allowing relatively open regional elections and negotiating with the opposition in Paris and then Barbados –, all his old strategies can be seen at work once more in the current handling of Machado’s candidacy. After the outcome of the primaries, the Maduro government immediately went on the offensive, casting doubt on Machado’s electoral success and calling the process fraudulent to delegitimise it. Only days after said declarations, the results – which were organised by an independent commission whose members were selected by consensus among polled opposition leaders, without the involvement of the CNE – were overruled by the TSJ. The Supreme Court also confirmed Machado’s ban beforehand, having been first enacted in 2015 for one year before in August 2023 being post facto extended to 15 years.

The government agreed to sanction the opposition primaries taking place via the CNE as part of the Barbados Agreement, but unlikely as a gesture of goodwill. The opposition has never been a complete monolith and the primaries were an opportunity for Maduro to showcase the cracks inside the opposition as well as receive international legitimacy in the process. The overwhelming victory of Machado and consequent unification of the opposition movement behind her candidacy was therefore an unexpected outcome that pushed the government towards classical repressive measures.

A judicial process to lift a political ban on opposition candidates was put in place by Maduro’s regime in November 2023, as a way of keeping Machado at bay through bureaucratic means without directly refusing her entry. This had a twin purpose:

to “comply” with the Barbados Agreement and maintain a performative legal process that would deter US President Joe Biden from reimposing sanctions and

to stall the opposition’s momentum until such time public attention on Corina’s victory fades away and internal fighting among opposition elites resumes.

In January 2024, both Machado’s and Capriles Radonski’s requests to lift the ban were rejected by the TSJ, leaving the two most popular opposition candidates out of the race.

Another countermeasure that the Maduro government has used is to shift the population’s attention away from Machado and her candidacy by reigniting international grievances regarding the territory of Essequibo, a geographic area constituting a source of dispute between Venezuela and Guyana ever since the 1960s. As a national issue on which Machado cannot have a diametrically opposed position to Maduro without souring national sentiment, this act of diversion has allowed the government to be the only voice in the related discussions and therewith keep its opponent out of the limelight.

Autocracies hold elections as one means of maintain their grip on power; they are a source of legitimisation, an opportunity for co-optation, and a great indicator of which leaders must be repressed to avoid further threats to the regime, even if it tends to produce a burst of instability during the process (Knutsen, Nygård, and Wig 2017). But co-optation is not an option during the course of presidential elections: the Venezuelan state has a centralised body with an extremely powerful executive branch; unlike in regional and local elections, or even in legislative ones, losing the presidency would represent a direct threat to the regime’s survival, particularly with Machado herself considered one of the most radical anti-Chavismo candidates.

How Autocracies Crumble: Venezuela in 2019 versus in 2024

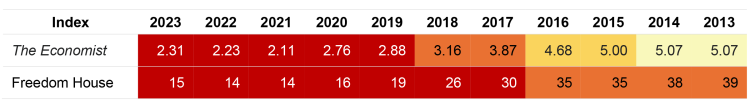

The government of Venezuela has, at least since 2006, been considered to have reverted from being a liberal democracy to an authoritarian state (Haggard and Kaufman 2021). Under Maduro, it has been widely considered an autocracy, with most democracy indexes categorising it as a hybrid regime or a full authoritarian state (Table 2).

Table 2. Venezuelan Democracy Indexes, 2013–2023

Sources: Freedom House (n.d.), The Economist (n.d.).

Notes: Red / deep orange = authoritarian state; light orange / yellow = hybrid regime.

Therefore, it is important to understand under what conditions authoritarian states can transition towards democracy. The study of Kendall-Taylor and Frantz (2014) shows that most autocracies fall through insider-led operations, either coup d’états or “regular” outings without the use of force – such as elections, forced resignations, and consensus decisions on moving towards a democratic transition. Circumstances depend on the incumbent autocrat’s capacity to control elites:

Each of these modes of [regular] departure requires that elites are capable of constraining the decisions and behavior of leaders. When autocrats lose office via an election, for example, regime insiders must have agreed to hold elections that were free and fair enough for an incumbent to actually lose. (Kendall-Taylor and Frantz 2014: 38)

This means the capacity to rein in (either through repression or co-opting) the current political, security, and economic elites becomes paramount to avoid insider-led outings.

Nevertheless, the same authors also highlight that since 2010 the number of autocratic breakdowns induced by mass revolt has increased significantly. Furthermore, unlike with insider-led exits – which tend to have only a 50 per cent probability of turning into democratic transition –, autocratic breakdowns ensuing from a popular uprising see a transition to democracy around 80 per cent of the time (Kendall-Taylor and Frantz 2014). Such outbursts of dissent can be sparked by a range of factors, but the capacity of the regime to hinder and weather them becomes key to avoiding removal from office.

Compared to the economic, security, and social conditions that Maduro faced before COVID, particularly in 2018–19, the regime today is presented with a more favourable scenario to avoid both kinds of outings. First, during the period 2014–2019, the fall of oil prices and the divestment of the Venezuelan oil industry, along with harmful macro-economic policies and widespread corruption, led to the starkest economic crisis in Venezuela’s modern history. The country suffered the highest inflation rate in the world, peaking in 2018 at a figure between 130,000 per cent according to the Venezuelan Central Bank (BCV) and over 1,500,000 per cent according to the opposition-led Financial Commission of the National Assembly (OVF) (see Table 3 below). Gross domestic product contracted by around 65 per cent between 2013 and 2019, according to a review by the United Nations’ Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean,with a further contraction of 30 per cent in 2020 on top (CEPAL 2021). Along with the general political repression and social insecurity, this led to a massive migration of Venezuelans to other countries in Latin America, with the numbers involved reaching over four million by 2019 according to the UN.

Table 3. Inflation Rates in Venezuela (in %), 2013–2023

Year | BCV | OVF |

2013 | 52.20 | - |

2014 | 68.50 | - |

2015 | 180.90 | - |

2016 | 274.40 | 550 |

2017 | 862.60 | 2,683.70 |

2018 | 130,060 | 1,698,488.20 |

2019 | 9,585.50 | 7,374.40 |

2020 | 2,968.80 | 3,713 |

2021 | 686.40 | 660 |

2022 | 234.10 | 305.70 |

2023 | 182.90 | 181.60 |

Sources: BCV and OVF.

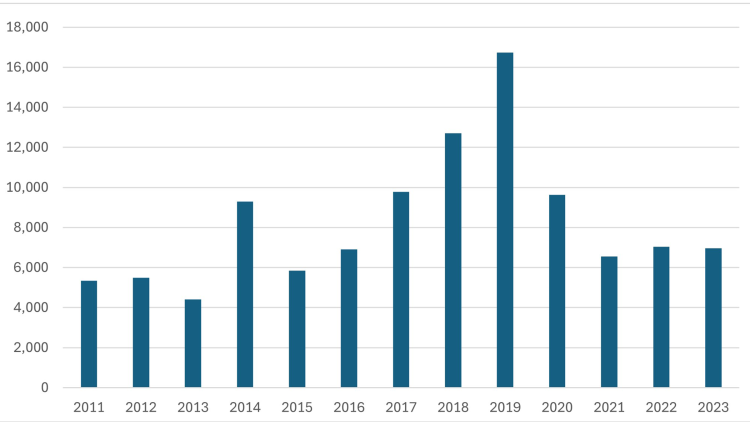

Furthermore, from 2014 to 2019 the Maduro government faced successive waves of contestation from opposition leaders and the public in the shape of protests (see Figure 1 below). These were induced by a combination of heavily deteriorating economic conditions and the extensive persecution of political opponents challenging the newly arrived and significantly less charismatic Maduro.

Figure 1. Protests in Venezuela by Year, 2011–2023

Source: Observatorio Venezolano de Conflictividad Social.

Incapable of maintaining internal legitimacy through clientelist practices with regards to the general population, and having lost the national parliamentary elections in 2015, the government weaponised the judiciary to render parliament powerless, created a parallel “Constitutional Assembly,” and relied also on repression and censorship. As noted, this served to heavily tarnish its reputation as a “popular democracy” internationally. This, in turn, forced it to increase ties with international outcasts or strong revisionist states to avoid isolation, including China, Iran, North Korea, Russia, and Turkey.

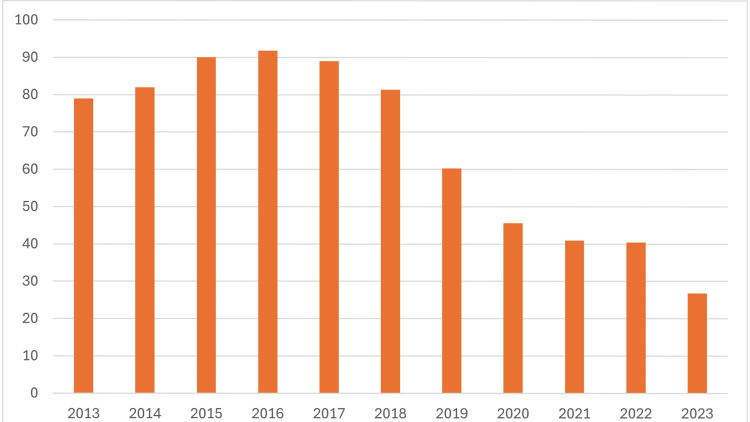

Finally, security would hit a historic low, with violent deaths reaching a peak of 90 per 100,000 inhabitants in 2016 (see Figure 2 below). Caracas had come to be considered the most dangerous city in the world as of 2015 according to the Consejo Ciudadano para la Seguridad Pública y la Justicia Penal (CCSPJP), a Mexican non-governmental organisation (Lozano 2016). During this crisis, Maduro relied on several para-institutions to maintain control over national territory without involving the official security forces, including colectivos, pranatos, and Colombian guerrilla groups. The colectivos are a government-supported organisation made up of ruling-party followers, civilians, undercover law-enforcement officials, and delinquents paid to clamp down on people living in the low-income zones of urban Venezuela, where the police dare not enter. It has been argued that by 2017 up to one-tenth of the country’s urban space was under the control of colectivos (Corrales 2020).

Pranatos or “mega-gangs,” meanwhile, are criminal organisations over 50 members in size that are normally controlled by a pran or “leader,” who tends to operate from inside a prison they rule the roost over. They rely on drug trafficking, extortion, and kidnapping throughout the country to sustain themselves. Despite gangs being prominent since the turn of the new millennium in Venezuela’s cities, from 2014 onwards the government provided these pranatos with safe havens (known as zonas de paz, “peace zones”): namely, territories the security forces cannot enter without a court order. In these spaces, mega-gangs were allowed to grow and function as a de facto form of government (Polga-Hecimovich 2019).

Another important actor constellation was the splinter groups of the Colombian ELN and FARC guerrillas, which have been a continued presence on Venezuelan territory, being allowed to persist and control hard-to-reach areas of the country such as Amazonas, Apure, or Tachira states. Guerrillas, pranatos, and the military share control over these respective areas, particularly in zones with gold-mining operations, which these groups extract and sell illegally. It was under dire economic conditions and significant political upheaval that Maduro came to rely on these para-states to maintain control over the country, while providing them with access to illegal operations and impunity in exchange (Corrales 2020).

Figure 2. Violent Deaths in Venezuela per 100,000 Inhabitants by Year, 2013–2023

Source: Observatorio Venezolano de Violencia.

Economic conditions have since significantly improved. Oil production scaled up from 400,000 barrels a day in 2021 to 700,000 barrels a day by 2023, mainly due to a change in management of Venezuela’s national oil company PDVSA as well as to an anti-corruption campaign. In tandem, there was an increase in the oil price from around USD 40–60 a barrel in the period 2015–2019 to around USD 80–90 a barrel between 2021 and 2023; Venezuelan revenues have, as such, significantly increased in the last three years. Hyperinflation finally subsided in 2021, which despite still seeing a triple-digit annual inflation rate (see Table 3 above) represented a qualitative change in Venezuelans’ perception of the economic crisis facing their country.

Security conditions have also changed. Control over national territory, formerly lost to gangs and paramilitary groups, has been partly recovered by the Maduro regime through violent military and police campaigns. Homicide rates in the country plummeted to 26.8 per 100,000 inhabitants in 2023. This is due to a combination of factors, including:

extermination campaigns by the Venezuelan government first through the Operation for the Liberation of the People (OLP) in 2015 and then furthered with the creation of the police special forces, FAES;

changed economic conditions that reduced revenues from muggings and kidnappings as well as access to bullets and weapons; and

the huge out-migration taking place since 2014. Particularly 2023 saw a reduction of 25 per cent in violent deaths compared to 2021 and 2022.

Control over the states bordering Colombia (Apure, Merida, Tachira), lost to the latter’s dissident guerrilla groups, has been partly recovered through military operations taking place in 2022 and 2023, sometimes in alliance with one guerrilla group to overcome the other. Major prison raids were executed in 2023 to quash gangs and retake control of the penitentiary system. The largest organised gangs, like the Tren de Aragua, were also tackled hereby.

Internal and International Opposition Has Waned

Not only have security, social, and economic conditions changed, but both internal and international opposition has faded in the last few years too. Internally, contestation from parties, NGOs, and educational institutions has been tackled through legislation, judicial takeover, and arbitrary imprisonment, while popular activists have been driven out of the country or arrested. Humanitarian agencies, which have become a parallel provider of public services where the government does not reach, have been under scrutiny and persecuted when suspected of having politically motivated agendas. The “Ley Antisociedad,” approved in August 2023, allows the government to take over an NGO and replace its management staff when they are found to be “working against the state.” Opposition from campuses, which was key during the protest era of 2014–2019, has been reduced as a consequence of the principle of major universities’ autonomy (such as the Central University of Venezuela (UCV) and the University of Zulia (LUZ)) being breached. Minor political parties’ leaders have been arrested, and in some cases these groupings have been taken over by the government – such as was the case with the Venezuelan Communist Party (PCV).

On the other hand, international pressure both regionally and globally has receded due to international crises and changes of government elsewhere. During the troubled years of 2014 to 2019, the Venezuelan government tarnished the country’s reputation regionally and internationally; the arrival into office of right-leaning governments in Argentina (Mauricio Macri), Brazil (Jair Bolsonaro), and Colombia (Iván Duque) catalysed the creation in 2017 of a regional coalition in favour of the Venezuelan oppositional “Lima Group,” seeking to support a democratic transition in the latter country. It was backed by a number of governments in Latin America and the Caribbean as well as Canada, the EU, and the US. The Lima Group reached its zenith in 2019 when opposition lawmaker Juan Guaidó declared himself interim president of Venezuela, creating a parallel government with international support from over 48 countries including the US and most EU member states.

The US and the EU were also then heavily involved in supporting a democratic transition in Venezuela. Some of the negotiations taking place between the opposition and the incumbent regime were hosted by European states (Oslo 2019, Paris 2022) while the US under President Donald Trump constantly antagonised Maduro; both the US and the EU imposed individual sanctions on Venezuelan government officials and their family members, too. In 2019, furthermore, they both recognised the interim presidency of Guaidó and imposed a battery of sanctions including the prohibition of oil and gold imports from Venezuela, the country’s exclusion from the international financial system, as well as general bans on trade with businesses aligned with the Maduro government.

These conditions have since drastically changed both regionally and internationally. The Lima Group slowly crumbled with the ascent of left-wing governments in Argentina in 2019 (Alberto Fernandez), Colombia in 2022 (Gustavo Petro), and Brazil in 2023 (Lula da Silva), while other members have fallen into internal crisis (Bolivia, Ecuador, Peru). The Maduro regime has managed to overcome the regional isolation the Lima Group imposed on the country, and open opposition has waned in consequence – except for in Argentina, following the unexpected victory of Javier Milei late last year.

In the US, the Biden administration’s taking of office in 2021 subsequently focused on lifting back up the domestic economy and then on the rapidly unfolding crises in Ukraine (2022–) and in Gaza (2023–). With an energy crunch caused by Russia’s weaponisation of its oil and gas resources, Biden decided to lift sanctions on Venezuela as part of the Barbados Agreement; in return, Maduro was to provide the conditions for free elections and allow opposition candidates to compete in 2024. Nevertheless, Venezuela’s president has to date not abided by the terms of the agreement while the Biden administration is currently too busy dealing with the aforementioned crises further afield and too worried about the possibility of increasing gas prices and Venezuelan migrants to enforce the agreed measures.

Meanwhile in Europe, EU governments have scaled back their opposition significantly. Some countries like France, Italy, and Spain have even given signals of a rapprochement with Caracas. Others like Germany and Netherlands are reluctant to follow suit unless Maduro demonstrates the will to allow democratic processes to occur, but active opposition has subsided.

What Comes Next: The Role of a Unified Opposition and International Support

Despite the opposition being unified under the leadership of Machado, as the elections draw closer it is, as such, likely that other opposition leaders will try to break rank by throwing their own candidates into the ring. The government has already provided incentives to do so by rejecting a lifting of the ban on Machado and Capriles Radonski and bringing the presidential elections forwards to July 2024. If new candidates that are not threatening to the incumbent regime do emerge, this would further fragment and delegitimise the opposition – Maduro’s ultimate goal here.

There are, nevertheless, a few alternatives available to the opposition and willing external actors if the Venezuelan government is to be cornered, and hence forced into either a relaxation of its grip on power or into increased repression and therewith greater delegitimation of its regime. The banning of Machado and Capriles Radonski does leave those seeking power without legitimate candidates for office, but it does not negate the possibility of Machado backing someone else in her place who still represents her ideas and is considered an outsider to the mainstream opposition. For this reason, Machado announced her support for Corina Yoris just days before the end of the time period allocated by the CNE to officially register candidates. Nevertheless, Yoris was prohibited from registering; meanwhile, minutes before the deadline, two opposition parties broke rank to inscribe Rosales – an opposition leader who does not enjoy popular support – as their own candidate.

Despite the fragmentation of the opposition, Maduro’s clearly undemocratic actions provide ample opportunity for external actors such as the US and the EU to threaten his government with the reimposition of sanctions, which would once again tarnish Venezuela’s reputation regionally and see it internationally isolated. Furthermore, such a course of action would give the opposition justification to incite protests and intensify contestation – that as long as further fragmentation inside the MUD does not occur and Machado continues to exert control over the coalition. Machado could also decide to back Manuel Rosales as candidate; in the current circumstances, it can be argued that any candidate with her backing, independently of their legitimacy, would beat Maduro in free and fair elections. This will force the incumbent to choose between banning Rosales from the race (which would only further delegitimise his rule), attempting to render the new candidate unelectable by discrediting him, or tampering with the election process to curtail the latter’s reach.

Even under this scenario, and regardless of whether protests erupt anew in the country, the probability of Maduro willingly transferring power is close to zero. With a reinvigorated security and para-security apparatus, along with stabilised revenues from the export of oil and illicit goods, the regime also currently finds itself better placed to weather popular dissent and clamp down on the remnants of organised opposition. The Venezuelan president’s co-optation of economic, security, and even minor political elites by offering them access to illicit operations or low-level government positions is very feasible, too – for example, via the legislative elections of 2025. The EU must, then, bear all this in mind as it decides key next steps.

Fußnoten

Literatur

BCV (Banco Central de Venezuela) (n.d.), Consumidor | Banco Central de Venezuela, accessed 26 March 2024.

CEPAL (Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe) (2021), Balance Preliminar de las Economías de América Latina y el Caribe 2020, February, accessed 26 March 2024.

Corrales, Javier (2020), Authoritarian Survival: Why Maduro Hasn’t Fallen, in: Journal of Democracy, 31, 3, 39–53.

Freedom House (n.d.), Freedom in the World, accessed 26 March 2024.

Gerschewski, Johannes (2013), The Three Pillars of Stability: Legitimation, Repression, and Co-Optation in Autocratic Regimes, in: Democratization, 20, 1, 13–38, accessed 26 March 2024.

Haggard, Stephan, and Robert Kaufman (2021), The Anatomy of Democratic Backsliding, in: Journal of Democracy, 32, 4, 27–41.

Kendall-Taylor, Andrea, and Erica Frantz (2014), How Autocracies Fall, in: The Washington Quarterly, 37, 1, 35–47, accessed 26 March 2024.

Knutsen, Carl Henrik, Håvard Mokleiv Nygård, and Tore Wig (2017), Autocratic Elections: Stabilizing Tool or Force for Change?, in: World Politics, 69, 1, 98–143, accessed 26 March 2024.

Lozano, Daniel (2016), Caracas ya es la ciudad más violenta del planeta, in: El Mundo, 27 January, accessed 26 March 2024.

Martin, Heather (2017), Coup-Proofing and Beyond: The Regime-Survival Strategies of Hugo Chávez, in: Latin American Policy, 8, 2, 249–262, accessed 26 March 2024.

Observatorio Venezolano de Conflictividad Social (n.d.), Informes Tendencias de Conflictividad, accessed 26 March 2024.

OVF (Observatorio Venezolano de Finanzas) (2018), Home, accessed 26 March 2024.

Observatorio Venezolano de Violencia (n.d.), Informe Anual de Violencia, accessed 26 March 2024.

Polga-Hecimovich, John (2019), Organized Crime and the State in Venezuela under Chavismo, in: Bagley, Bruce, Jorge Chabat, and Jonathan D. Rosen (eds), The Criminalization of States: The Relationship between States and Organized Crime, Chapter: 9, Lexington: Lexington Press, 189–207.

The Economist (n.d.), Democracy Index 2023, accessed 26 March 2024.

Redaktion GIGA Focus Lateinamerika

Lektorat GIGA Focus Lateinamerika

Regionalinstitute

Forschungsschwerpunkte

Wie man diesen Artikel zitiert

Renzullo Narvaez, Jesus Renzullo (2024), Conditions for Democratic Transitions: Venezuela’s 2024 Elections, GIGA Focus Lateinamerika, 2, Hamburg: German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), https://doi.org/10.57671/gfla-24022

Impressum

Der GIGA Focus ist eine Open-Access-Publikation. Sie kann kostenfrei im Internet gelesen und heruntergeladen werden unter www.giga-hamburg.de/de/publikationen/giga-focus und darf gemäß den Bedingungen der Creative-Commons-Lizenz Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 frei vervielfältigt, verbreitet und öffentlich zugänglich gemacht werden. Dies umfasst insbesondere: korrekte Angabe der Erstveröffentlichung als GIGA Focus, keine Bearbeitung oder Kürzung.

Das German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) – Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien in Hamburg gibt Focus-Reihen zu Afrika, Asien, Lateinamerika, Nahost und zu globalen Fragen heraus. Der GIGA Focus wird vom GIGA redaktionell gestaltet. Die vertretenen Auffassungen stellen die der Autorinnen und Autoren und nicht unbedingt die des Instituts dar. Die Verfassenden sind für den Inhalt ihrer Beiträge verantwortlich. Irrtümer und Auslassungen bleiben vorbehalten. Das GIGA und die Autorinnen und Autoren haften nicht für Richtigkeit und Vollständigkeit oder für Konsequenzen, die sich aus der Nutzung der bereitgestellten Informationen ergeben.