- Home

- Publications

- GIGA Focus

- Military Involvement in COVID-19 Responses: Comparing Asia and Latin America

GIGA Focus Global

Military Involvement in COVID-19 Responses: Comparing Asia and Latin America

Number 3 | 2023 | ISSN: 1862-3581

Across the world, governments mobilised the military to support COVID-19 relief efforts. Especially in Asia and Latin America, where the military was extensively involved, this raised concerns about the negative implications for democratic quality and human rights. However, only in a few of the two regions’ countries did the military hijack or supplant civilian politics during the pandemic.

In both regions, militaries performed numerous tasks during the pandemic, staffing the health bureaucracy, producing medical equipment, providing healthcare services, delivering logistics, and enforcing public-security measures.

The extensive reliance on the military’s organisational resources, however, did not necessarily lead to the political ascendance of the armed forces or the erosion of democratic quality.

Military participation in COVID-19 relief efforts undermined democracy and human rights only where the armed forces had been a pivotal actor in the context of institutionally weak democracies or militarised dictatorships already prior to 2020.

Policy Implications

Where democratic processes, the rule of law, and civilian control are well institutionalised, the deployment of the military is unlikely to have direct negative repercussions for democratic quality. External support for security sector reform to strengthen military capabilities should be integrated into a general approach fortifying the institutions of democracy and accountability.

The COVID-19 Pandemic as a Military Task

After the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a public health emergency of international concern on 30 January 2020, governments across the globe took action to contain the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus and prevent their health systems from collapsing. According to data from Erickson and colleagues (Erickson, Kljajić, and Shelef 2023: 357), 95 per cent of all countries relied on their militaries to supplement under-resourced healthcare systems, enforce COVID-19 policies, and to support civilian logistical and infrastructure capacities. Governments justified the military’s extensive involvement in national pandemic responses by the imperative of protecting lives in an environment of weak civic capacities and overwhelmed civilian institutions. Yet, heavily armed soldiers patrolling the streets to enforce quarantines, military personnel distributing food in remote areas, or army medics vaccinating people raised concerns about the appropriateness of this close involvement and its implications for the military’s political power, as well as potentially negative impact on citizens’ political rights and civil liberties.

While reliable data such as case numbers and excess mortality rates are missing for many states in Asia, it is evident that the two regions were hotspots of the global waves of infection during the pandemic. In addition, many countries had long histories of military involvement in politics, weak institutions of civilian control, and legacies of egregious human rights violations perpetrated by soldiers against their own citizens. Moreover, military involvement was not a problem of the distant past. According to data from the Cline Center for Advanced Social Research (2022), five military-coup attempts had taken place in Asia and Latin America between 2010 and 2019: in Bangladesh (2012), Thailand (2014), Venezuela (2015, 2019), and Bolivia (2019). In addition, militaries had extensive power in the regime coalitions of closed and electoral autocracies in both regions, including Bangladesh, Cuba, Myanmar, Pakistan, Thailand, and Venezuela. Finally, in both regions, the pandemic often occurred in a context of long-standing democratic defects, socio-economic distress, and political crisis. Examples in Latin America include Bolivia, Brazil, Venezuela, as well as most states in Central America, while in Asia countries such as Cambodia, India, the Philippines, Sri Lanka, and Thailand had suffered from democratic backsliding prior to the pandemic.

In contrast to earlier waves of autocratisation, these erosions of democratic practices and institutions were caused not by generals and soldiers but by elected governments themselves. This does not mean that the military passively watched on as democracy was dismantled. In El Salvador under President Nayib Bukele (2019–) and the Philippines under President Rodrigo Duterte (2016–2022), for instance, the army supported executive aggrandisement by their civilian heads. In Myanmar, in contrast, the military itself became a “gravedigger of democracy” (Kuehn 2019) on 1 February 2021, when it staged a coup and took over the government amid the woes of the COVID-19 pandemic. In many cases, however, the military was merely a bystander, neither participating in democratic backsliding nor protecting the constitutional order from retrogression or authoritarian reversal.

Contours of Military Involvement in COVID-19 Responses

We collected monthly data on pandemic-related military deployments as part of state-led COVID-19 measures in 34 countries in Asia and Latin America from 1 January 2020 to 31 December 2021 (Croissant et al. 2023). To conceptually capture the wide variety of armed forces’ activities in national pandemic efforts, we differentiate five broad fields of action, which together comprise a total of 16 distinct categories of activities (which we call “operations”):

A. Health policy-making: This relates to the military’s participation in shaping the policy agenda regarding government responses to the pandemic. B. Military production: This includes the mobilisation of military industrial capacities to develop and produce medical supplies (vaccines, personal protective equipment, and similar) to compensate for gaps in civilian-healthcare supply chains. C. Healthcare: This captures the use of military capacities to assist civilian health systems and with patient care. D. Logistics: This comprises military provision of logistical support beyond direct healthcare to aid civilian humanitarian efforts. E. Public security: This relates to military mobilisation to enforce containment measures seeking to prevent the SARS-CoV-2 virus’s spread.

Table 1 below shows how we disaggregate these five fields of action into 16 distinct types of military operation:

Table 1: The Nature of Military Involvement in COVID-19 Responses

Field of action | Operations |

Health policy-making | (1) military personnel take leading roles in the health ministry (2) military personnel take leading roles in national emergency-response committee tasked to advise the government on pandemic management |

Military production | (3) military industrial production sites or research facilities develop or manufacture medical products for civilian consumption |

Healthcare | (4) military personnel disseminate information to generate awareness on the disease among the general public (5) military personnel are involved in the decontamination of public areas or facilities (6) military personnel are involved in COVID-19 screening, tests, or vaccinations for civilians (7) military personnel cares for civilian coronavirus patients |

Logistics | (8) military personnel construct isolation or healthcare facilities (9) military personnel distribute or transport basic goods (food, water, hygiene products) to vulnerable communities (10) military personnel repatriate nationals stranded abroad (11) military personnel distribute or transport COVID-19-related medical products (12) military personnel transport COVID-19 patients or civilian medical personnel |

Public security | (13) military enforces international borders (aerial, maritime, terrestrial) alone or alongside law enforcement (14) military performs street patrols, alone or alongside law enforcement, to ensure compliance with COVID-19 measures (15) military performs crowd or riot control, alone or alongside law enforcement (16) military protects infrastructure critical to COVID-19 efforts (hospitals, warehouses, medical-product manufacturing complexes) |

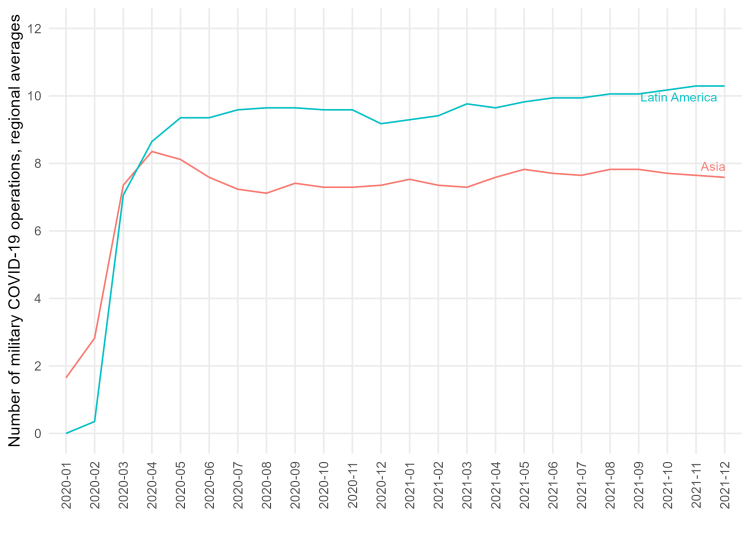

Figure 1 below shows the average number, month-to-month, of COVID-19-related military operations between January 2020 and December 2021 in the two regions.

Figure 1. COVID-19-Related Military Operations, January 2020–December 2021

Source: Authors’ own compilation, based on Croissant et al. (2023).

Notes: For the list of countries, see Figure 3.

Once the WHO had declared COVID-19 a public health emergency, governments were evidently quick to mobilise their militaries. By late March 2020, armies across both regions shouldered numerous tasks to support these response efforts. While Asian governments tended to mobilise their troops somewhat earlier due to the SARS-CoV-2 virus originating locally, authorities in Latin America provided their armed forces with broader activity profiles. From June 2020 onwards, Asian militaries performed, on average, about eight operations, while their Latin American counterparts carried out, on average, ten. Moreover, once deployed, militaries in both regions generally remained involved in pandemic responses until the end of 2021, with the average number of military operations remaining almost unchanged. Nonetheless, there are substantial differences both in terms of activity profiles as well as of the extent of involvement within the respective regions.

On average, Latin American militaries had broader activity profiles than their Asian counterparts, as the former were involved in their countries’ pandemic responses to a greater extent than the latter equivalently were. Nevertheless, there are also many similarities. In both Latin America and Asia, troops were extensively involved in providing healthcare services, supporting or conducting the full range of COVID-19-related activities in this regard: disseminating information; decontaminating public areas; and, testing, vaccinating, as well as caring for patients. Furthermore, military personnel also conducted a host of logistical operations to support pandemic responses, and many militaries in Asia and especially Latin America contributed hereto by producing COVID-19-related medical equipment. While healthcare, logistics, and production had, thus, a heavy military footprint in both regions, national pandemic policy remained mostly in the hands of civilians. In both Asia and Latin America, active-duty or recently retired military officers played a prominent role in health ministries or emergency-response committees only in a handful of cases. Finally, even though Asian armies were, on average, less involved than their Latin American counterparts in pandemic-related public-security operations, militaries in both regions were deployed to secure borders, patrol the streets, enforce curfews, perform crowd- and riot-control functions, and guard critical infrastructure.

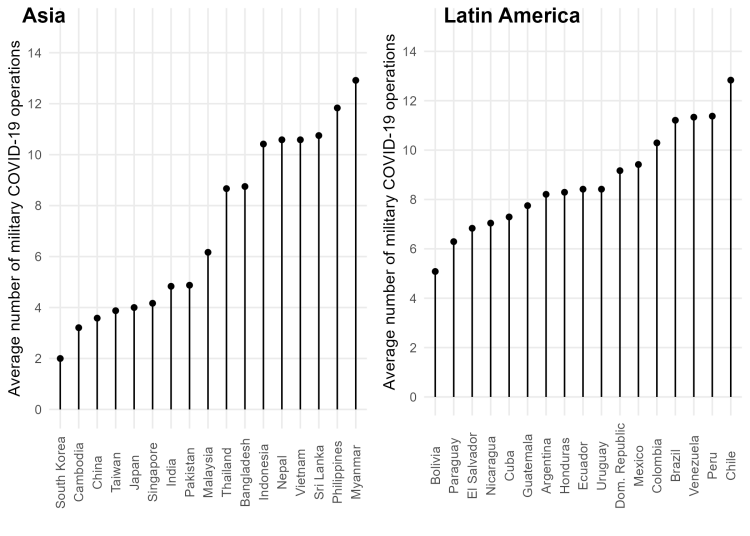

Figure 2. COVID-19 Military Operations by Country, January 2020–December 2021

Source: Authors’ own compilation, based on Croissant et al. (2023).

The regional perspective, of course, masks stark differences across individual countries within the same one. Figure 2 shows the average number of operations conducted by each of the total 34 armed forces in question from January 2020 to December 2021. In Asia, there is a group of six countries (Cambodia, China, Japan, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan), where military personnel were deployed only marginally in COVID-19 relief efforts. On the other hand, in six other countries (Indonesia, Nepal, the Philippines, Sri Lanka, Vietnam, and especially Myanmar) the military was involved in a broad spectrum of related endeavours. In the remaining five Asian countries studied (Bangladesh, India, Malaysia, Pakistan, and Thailand), military personnel played a significant though less prominent role – a finding that is somewhat surprising given the heavy political and administrative power of the military in Pakistan and Thailand.

In Latin America, there is less variation across countries. Still, there is a noticeable gap between cases such as Bolivia and Paraguay, where the military was involved, on average, in five to six COVID-19-related operations, and Brazil, Chile, Peru, and Venezuela where the equivalent figure stood at 11 or more. In sum, however, there is more regional variation in Asia than in Latin America, and these differences were mainly at the lower end of the military-involvement scale. In Asia, eight countries conducted fewer than six such operations, while in Latin America this was true only in Bolivia.

Consequences of Military Participation in COVID-19 Responses

When deployed as part of COVID-19 relief efforts in early 2020, many observers were worried that their extensive involvement herein could enhance the military’s societal and political clout and might contribute to the erosion of human rights and the rule of law (Chandran 2020; Croissant and Trinn 2022; Isacson 2020; Mani 2020). Moreover, drawing on numerous examples from before the pandemic, some observers warned that extensive reliance on the military could lead to the further erosion of democratic quality and threaten political rights and civil liberties, especially if the armed forces engaged in public-security and surveillance operations (Croissant 2020; Greitens 2020). Descriptive analyses offer insight into the effects of military operations during the COVID-19 pandemic on civil–military relations, democratic quality, and human rights.

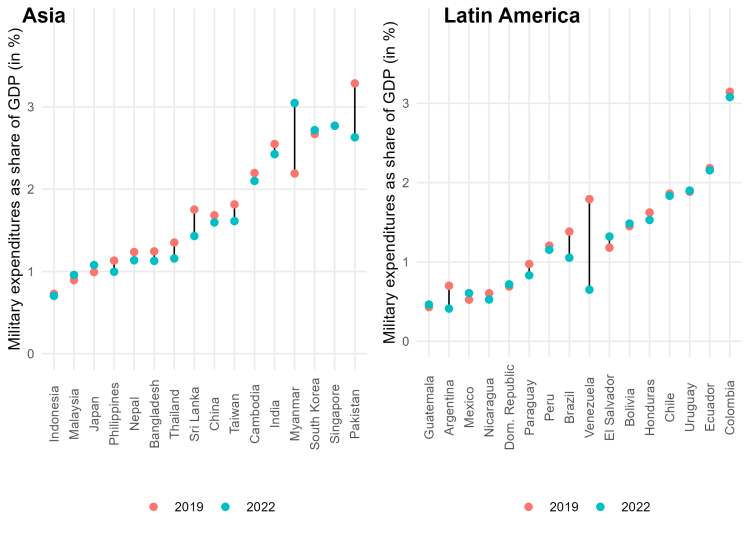

To evaluate trends regarding the military’s societal and political power, expenditure is one measure of its control over societal resources while influence on the formation and dissolution of governments captures its direct political power. Drawing on data from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI 2023), the barbell plots in Figure 3 compare military expenditure as a share of gross domestic product for the period 2019 to 2022. Overall, the graphs suggest that the pandemic did not lead to the military’s greater access to their society’s economic wealth. In both regions, military expenditure was relatively stable, with changes therein only minor. Moreover, most budget amendments here were negative, as countries allocated smaller shares of their national wealth to their militaries in 2022 than they had done prior to the pandemic. Interestingly, this is even the case for countries such as Brazil, Sri Lanka, and Venezuela, whose militaries had been particularly active in pandemic responses, but whose military expenditure as a share of GDP declined markedly.

Venezuela’s military spending saw a drastic reduction from about 1.8 per cent of GDP in 2019 to 0.7 per cent in 2022, due to a sudden spike in GDP without any adjustment of its relatively stable military budget. Other countries whose COVID-19 responses had been highly militarised such as Chile, Nepal, Peru, or the Philippines maintained similar levels of military expenditure as compared to before the pandemic. The increase in military expenditure as a percentage of GDP from 2.2 per cent to 3.1 per cent in Myanmar, meanwhile, had little to do with the pandemic itself but reflects shifting policy priorities after the coup d’état of 1 February 2021 and the subsequent escalation of political unrest and violence.

Figure 3. Changes in Military Expenditure as a Share of GDP, 2019–2022

Source: Authors’ own compilation, based on Croissant et al. (2023).

Notes: No available data for Cuba and Vietnam.

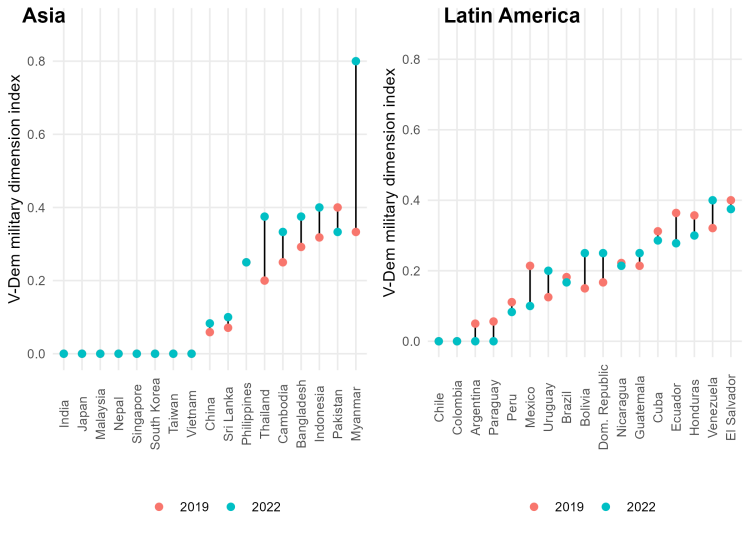

In some countries, the pandemic opened up a window of opportunity for military leaders to expand their political prerogatives. Further to the aforementioned February 2021 military coup in Myanmar, soldiers in El Salvador occupied the Legislative Assembly building on 9 February 2020 to coerce lawmakers into accepting President Bukele’s demand to accept a loan from the United States (Cline Center for Advanced Social Research 2022). To gauge the development of military influence on governments in Latin America and Asia during the pandemic, Figure 4 draws on the military dimension index published by the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) project. The index captures the “extent to which the appointment and dismissal of the chief executive is based on the threat or actual use of military force” (Coppedge et al. 2023: 293) on a scale from 0 (no military influence whatsoever) to 1 (total military domination of the executive).

Figure 4. Changes in Military Influence on the Executive, 2019–2022

Source: Authors’ own compilation, based on data from Coppedge et al. (2023).

Eight Asian countries, including the liberal democracies of Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan, can be considered completely free from military interference. In Latin America, only in Chile and Colombia did the military have no influence on government formation, while in Argentina and Paraguay the armed forces lost their (minimal) influence between 2019 and 2022. In Asia, military power over politics increased during the pandemic in seven countries. In countries such as China and Sri Lanka, this increase started from very low levels and was marginal. In contrast, in ones where the military already had above-average political power before the pandemic, such as Bangladesh, Cambodia, Indonesia, and Thailand, the V-Dem military dimension index increased significantly by roughly 0.1 points (ten percentage points). Unsurprisingly, the 2021 coup massively increased Myanmar’s military dimension index score, from 0.3 in 2019 to 0.8 in 2022. Exceptions are the Philippines, where military power in 2022 was equal to its 2019 level, and Pakistan, the only Asian country seeing a reduction in the military dimension index (from 0.4 in 2019 to 0.3 in 2022).

In Latin America, military influence on government formation increased in only five of the 17 studied countries between 2019 and 2022: Bolivia, the Dominican Republic, Guatemala, Uruguay, and Venezuela. In contrast, ten regional countries saw at least some degree of reduction in military power. In El Salvador, the army’s intervention on behalf of President Bukele did not translate into greater military influence on the executive. To the contrary, the country’s military dimension index score slightly contracted from a value of 0.4 in 2019, the highest of all the Latin American countries included in our analysis, to 0.38 in 2022.

Across both regions, some countries with highly militarised COVID-19 responses experienced an increase in the armed forces’ influence there, such as Bangladesh, Myanmar, and Venezuela, while others, like Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Nepal, the Philippines, and Vietnam, did not. At the same time, the military’s power increased in countries with limited COVID-19-related activity profiles for it such as Bolivia and Cambodia. This suggests that there is no linear connection between the extent of military involvement in pandemic responses and the differences in the armed forces’ influence on government formation between 2019 and 2022.

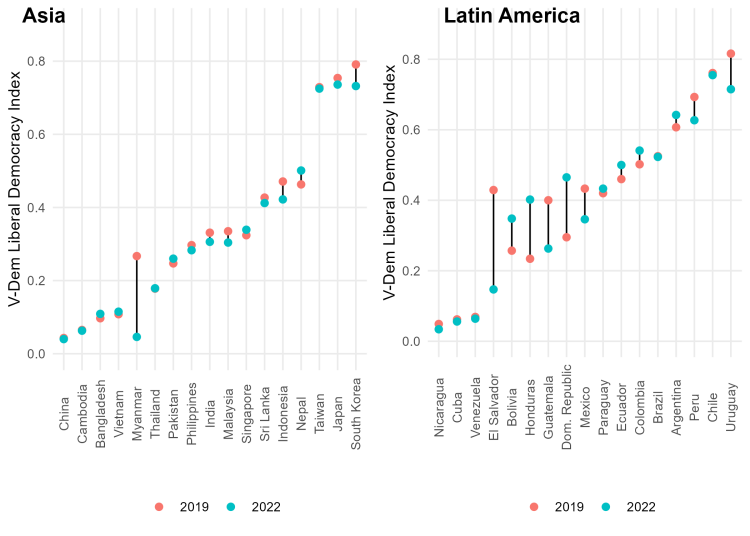

Turning to the relationship between military participation in COVID-19 relief efforts and the quality of democracy, Figure 5 shows V-Dem liberal democracy index (LDI) scores between 2019 and 2022. The LDI measures the extent to which a functional electoral regime is combined with effective safeguards for “civil liberties, strong rule of law, an independent judiciary, and effective checks and balances that, together, limit the exercise of executive power” (Coppedge et al. 2023: 45). It ranges from 0, denoting the complete absence of elections and institutional checks and balances, to 1, marking the perfect implementation of the principles of liberal democracy. Across both regions, eight countries saw declines in their LDI scores by 0.05 points (five percentage points) or more in 2022 from the levels three years earlier. In Asia, these were South Korea (0.06), Indonesia (0.05), and Myanmar (0.22), while in Latin America, democratic quality dropped noticeably in Uruguay (0.1), Peru (0.07), Mexico (0.09), Guatemala (0.14), and El Salvador (0.28). The substantive erosion of the democratic quality of political processes and institutions occurred from high levels in the liberal democracies of South Korea and Uruguay or from medium levels of electoral democracy in Indonesia, Mexico, and Peru without triggering authoritarian reversal. In El Salvador and Guatemala, it resulted in the breakdowns of already highly defective democracies, whereas Myanmar experienced a further hardening of already-repressive authoritarian rule.

Interestingly, democratic backsliding was much more pronounced in the Latin American cases, with an average decline of 0.14 points on the LDI score in the five cases of democratic erosion, compared to 0.08 points thereon across the five Asian ones. While Nepal is the only case which experienced a substantial increase in its LDI score (by 0.04 points), the quality of liberal democracy improved in six Latin American countries between 2019 and 2022. However, ups and downs in democratic quality are not clearly correlated with the extent of military involvement in pandemic responses: in Colombia and Nepal, democracy scores improved despite their respective militaries conducting a wide range of COVID-19-related operations, while South Korea suffered from democratic erosion despite its armed forces’ low level of participation in these relief efforts.

Figure 5. Changes in V-Dem LDI Scores, 2019–2022

Source: Authors’ own compilation, based on data from Coppedge et al. (2023).

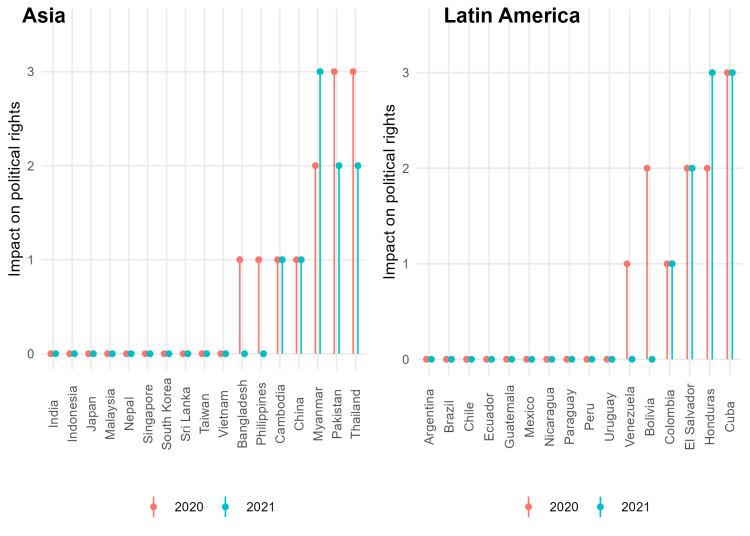

Of course, comparing democracy scores with the number of military operations during the COVID-19 pandemic cannot capture the complex dynamics and potential impact hereof. To evaluate the impact of the military’s activities on democratic quality, Figures 6 and 7 show the results of an expert survey in late 2021 and early 2022, which ranks the impact of military COVID-19-related operations on a range from 0 to 3, with 0 denoting no impingements and 3 representing severe, widespread, and systematic restriction of citizens’ rights and liberties in the given year.

Figure 6. Impact of Military COVID-19-Related Operations on Political Rights, 2020–2021

Source: Authors’ own compilation, based on Croissant et al. (2023).

Note: No data on the Dominican Republic.

In 12 of the 33 countries for which we have data, military COVID-19-related operations impinged on political rights. This includes countries such as Bangladesh, Cambodia, China, Colombia, and the Philippines, where infringements were limited either in scope or duration. However, military activities severely impacted on citizens’ political rights in another seven cases. These included three democracies with long histories of military involvement in politics (Bolivia, El Salvador, and Honduras) and four heavily militarised authoritarian regimes (Myanmar, Pakistan, Thailand, and Venezuela).

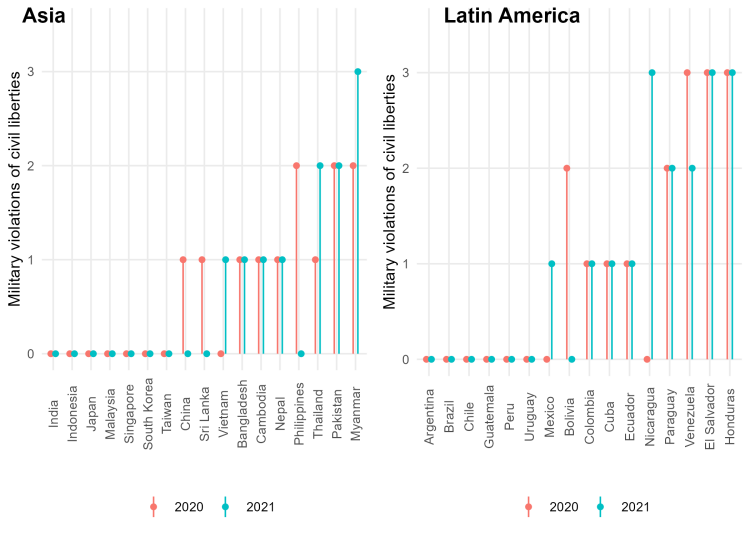

Finally, Figure 7 presents the results of the expert survey for the impact of military COVID-19-related operations on civil liberties. The same countries that saw the greatest impact on political rights also experienced the military curtailment of civil liberties during the pandemic. However, violations of civil liberties were more common than those pertaining to political rights: in 20 – that is, almost two-thirds – of the 33 countries for which we have data, the military was responsible for at least some violations of civil liberties. Restrictions imposed by the military on civil liberties were particularly problematic in six Latin American countries in one of the pandemic years. Again, there is not necessarily a direct relationship between militarised pandemic responses and civil rights infringements. In Myanmar, the Philippines (in 2020), and Venezuela, extensive military involvement went hand-in-hand with severe repression, whereas countries with a low military profile, such as Argentina, India, or Malaysia, tended to experience no civil rights violations. However, the cases of Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Sri Lanka, and Vietnam show that high degrees of military participation in COVID-19 relief efforts need not automatically impinge on civil rights. Finally, there are also highly repressive militaries which, overall, did not have an extensive activity profile in their nations’ pandemic responses. These include El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua (in 2021), Pakistan, and Paraguay.

Figure 7. Impact of Military COVID-19-Related Operations on Civil Liberties, 2020–2021

Source: Authors’ own compilation, based on Croissant et al. (2023).

What This Means in Practice

The deployment of the military during the COVID-19 pandemic was an almost universal instrument of crisis response throughout Asia and Latin America alike. While there are important differences between the two regions and across respective countries regarding the levels and forms hereof, virtually every Asian and Latin American government relied to some degree on the organisational resources and infrastructural capabilities of its armed forces. Despite this extensive involvement in relief efforts, however, civilian structures and decision-making processes would rarely be hijacked or supplanted by the military.

Accordingly, worries of a lasting militarisation of the state apparatus and public life because of the pandemic have proven unfounded – with notable exceptions, of course. In some countries the deployment of the armed forces to fight a national health emergency – however well-founded it may have been – also had negative and sometimes harsh consequences for democratic institutions, political rights, and civil liberties. This was particularly the case where – as in parts of Central America, as well as in Pakistan, Venezuela, and some Southeast Asian nations – extensive democratic backsliding had already occurred prior to 2020, with the military being a key political actor in the context of institutionally weak democracies or militarised dictatorships.

Between one-third and two-thirds of the studied countries experienced impingements on political rights and/or civil liberties directly related to military operations during the pandemic. Considering that 22 of the 33 countries examined were classified as electoral democracies in 2019, these are surprisingly high numbers. Nonetheless, it seems fair to conclude that COVID-19’s onset did not represent a critical juncture for civil–military relations in either Asia or Latin America. The pandemic rather accelerated earlier trends, such as the militarisation of law enforcement and public security in Central America, the prominent role of the armed forces in the national economy and business activities in several South and Southeast Asian countries, or the persistence of existing military prerogatives in politics and government.

The armed forces’ role in pandemic responses in the two regions, therefore, does not force external promoters of democracy, the rule of law, and democratic governance in the security sector to fundamentally rethink their approach. Negative examples such as El Salvador, the Philippines, and Venezuela simply confirm the already well-known insight that times of crisis are the hour of the executive. The preliminary evidence from global, large-N studies suggests where they are not forced to do so by strong institutions of horizontal, diagonal, and vertical accountability, governments tend to resort to the armed servants of the state to assert themselves and their claims to power (Knutsen and Kolvani 2023; Sorsa and Kivikoski 2023).

In contrast, where democratic processes, institutions of the rule of law, and mechanisms of civilian control are well developed and entrenched in society and politics, the deployment of the military – even in domains such as public order and security – is unlikely to have direct negative repercussions for democratic quality. Hence, lingering concerns that security sector reforms designed to strengthen the military’s capabilities and capacities could have adverse consequences during times of national crisis seem unwarranted. The “problems” associated with the armed forces’ participation in COVID-19 responses in Latin America and Asia had less to do with the military per se than with the long-standing weaknesses and shortcomings of democratic practices, institutions, and norms in the respective countries.

Footnotes

References

Chandran, Nyshka (2020), The Pandemic Has Given Armies in Southeast Asia a Boost, in: Foreign Policy (blog), 15 June, accessed 22 September 2023.

Cline Center for Advanced Social Research (2022), Coup d’État Project, accessed 22 September 2023.

Coppedge, Michael et al. (2023), V-Dem Codebook V13, Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project, accessed 22 September 2023.

Croissant, Aurel (2020), Democracies with Preexisting Conditions and the Coronavirus in the Indo-Pacific, in: The Asan Forum (blog), accessed 22 September 2023.

Croissant, Aurel, and Christoph Trinn (2022), Between Regression and Resilience: BTI Regional Report Asia and Oceania, Bertelsmann Stiftung Verlag.

Croissant, Aurel, David Kuehn, David Pion-Berlin, and Ariam Macias-Weller (2023), Militarization of State Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic in Latin America and Asia Pacific Dataset, GIGA Working Paper, 334, Hamburg: GIGA, accessed 26 September 2023.

Erickson, Peter, Marko Kljajić, and Nadav Shelef (2023), Domestic Military Deployments in Response to COVID-19, in: Armed Forces & Society, 49, 2, 350–371.

Greitens, Sheena Chestnut (2020), Surveillance, Security, and Liberal Democracy in the Post-COVID World, in: International Organization, 74, S1, E169–E190.

Isacson, Adam (2020), In Latin America, COVID-19 Risks Permanently Disturbing Civil-Military Relations, in: WOLA, 20 July, accessed 22 September 2023.

Knutsen, Carl H., and Palina Kolvani (2023), Fighting the Disease or Manipulating the Data? Democracy, State Capacity, and the COVID-19 Pandemic, 127, V-Dem Working Paper Series, Gothenburg: The Varieties of Democracy Institute, accessed 22 September 2023.

Kuehn, David (ed) (2019), The Military’s Impact on Democratic Development: Midwives or Gravediggers of Democracy?, Routledge.

Mani, Kristina (2020), ‘The Soldier Is Here to Defend You.’ Latin America’s Militarized Response to COVID-19, in: World Politics Review (blog), 21 April, accessed 22 September 2023.

SIPRI (2023), SIPRI Military Expenditure Database, accessed 22 September 2023.

Sorsa, Ville-Pekka, and Katja Kivikoski (2023), Covid-19 and Democracy: A Scoping Review, in: BMC Public Health, 23, 1668.

Editor GIGA Focus Global

Editorial Department GIGA Focus Global

Research Project

Regional Institutes

Research Programmes

How to cite this article

Kuehn, David, Aurel Croissant, David Pion-Berlin, and Ariam Macias-Weller (2023), Military Involvement in COVID-19 Responses: Comparing Asia and Latin America, GIGA Focus Global, 3, Hamburg: German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), https://doi.org/10.57671/gfgl-23032

Imprint

The GIGA Focus is an Open Access publication and can be read on the Internet and downloaded free of charge at www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publications/giga-focus. According to the conditions of the Creative-Commons license Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0, this publication may be freely duplicated, circulated, and made accessible to the public. The particular conditions include the correct indication of the initial publication as GIGA Focus and no changes in or abbreviation of texts.

The German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) – Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien in Hamburg publishes the Focus series on Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and global issues. The GIGA Focus is edited and published by the GIGA. The views and opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the institute. Authors alone are responsible for the content of their articles. GIGA and the authors cannot be held liable for any errors and omissions, or for any consequences arising from the use of the information provided.