- Startseite

- Publikationen

- GIGA Focus

- Remilitarisation in Asia: Trends and Implications

GIGA Focus Asien

Remilitarisation in Asia: Trends and Implications

Nummer 2 | 2024 | ISSN: 1862-359X

Recent years have seen a remilitarisation of many countries in South, Southeast, and Northeast Asia. While open coups remain an exception, there is a worrying trend among Asian nations of the military’s influence over politics, society, and the economy gradually increasing. This raises concerns about the prospects for liberal democracy, just socio-economic development, and stability in the region.

Since midway through the first decade of the new century, militaries in Asia have expanded their influence over the recruitment of personnel to government positions, therewith exercising veto power over political decision-making and engaging in repression of the opposition.

The region also is subject to an increasing material militarisation. Through rising budgets and large armies, many of the region’s militaries command substantial shares of their respective national financial and human resources. Combined, military entrepreneurship and a militarised bureaucracy provide the “deep state” with the necessary resources and capacities to penetrate and control politics and society.

These developments run parallel to an increased military presence in society, with many Asian armies maintaining extensive business interests and routinely conducting policing operations.

While the long-term repercussions of this multidimensional remilitarisation remain uncertain, historical precedent cautions against incremental militarisation in politics, society, and the economy.

Policy Implications

The remilitarisation of Asian societies threatens liberal democracy, equitable socio-economic development, and regional stability. European actors should, therefore, raise awareness of these trends and strengthen institutions of civilian control over the military. In an increasingly complex regional and international environment characterised by geopolitical tensions and autocratisation, this will only succeed if Europeans lead by example and ensure that their own military deployments align with transparency principles, human rights, and international law.

The Many Dimensions of Remilitarisation in Asia

Militarisation seems to be on the rise again in Asia. A coup against the civilian government of Myanmar in February 2021 was followed by a military-orchestrated parliamentary vote of no confidence in Pakistan’s democratically elected Prime Minister Imran Khan in April 2022. Thailand held two elections in recent times, in 2019 and 2023, but an alliance of military generals, royalist elites, and their proxy parties managed to deprive the real winners of access to political power. Most recently, in February 2024, Indonesian voters elected Defence Minister Prabowo Subianto, a former army general known for accusations of brutality and human rights abuses under the authoritarian Suharto, as president.

Beyond such obvious examples of direct military involvement in politics, militarisation in Asia takes a number of other forms, too. Many Asian governments, for instance, have relied on the military to fulfil a broad range of tasks beyond traditional national defence, both before and during the COVID-19 pandemic (Kuehn et al. 2023). Even since the latter’s end, many Asian states have continued to routinely rely on the military to bolster internal security, conduct law-and-order operations, or manage economic enterprises. At the same time, Asia is a hotspot for international conflicts and territorial disputes, including in the South China Sea, on the Korean Peninsula, between India and Pakistan, and across the Taiwan Strait. These conflicts are contributing to a surge in defence spending and therewith turning the region into a powder keg (Rudischhauser 2023).

The accelerated militarisation of states and societies in Asia has ensued, with potentially adverse effects on democratic governance, human development, and regional stability. Drawing on novel data, we show that the military plays important and diverse role in many Asian societies, being highly involved therein in certain parts of the region. However, there is considerable variance across subregions and countries, as well as different dimensions to that militarisation. Moreover, key indicators point more towards a continuance of existing trends rather than a recent resurgence of militarisation, especially in the political domain.

Patterns and Trends of Militarisation in Asia since the End of the Cold War

Militarisation is a multidimensional and gradual process in which “a society's institutions, policies, behaviors, thought, and values are devoted to military power and shaped by war” (Kohn 2009: 182). Drawing on the novel Multidimensional Measures of Militarisation (M3)dataset (Bayer et al. 2023b), we identify three main dimensions to militarisation: political, material, and societal. M3 presents data on 30 indicators of militarisation across 157 countries for the period 1990 to 2020, including on 20 states in South, Southeast, and Northeast Asia (Table 1 below).

Table 1. Asian Countries Included in the M3 Dataset

South Asia | Southeast Asia | Northeast Asia |

Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka | Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Timor-Leste, Vietnam | China, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea |

Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

Note: Data on Taiwan not included in M3.

Political Militarisation

Political militarisation denotes a process through which the military increases its power and influence over political decision-making. To evaluate whether the military’s political power has increased in Asia since the end of the Cold War, we examine three specific factors here:

the degree of military control over the selection of political elites;

the extent of military policymaking influence and political privilege; and

the occurrence of military repression against political and civil society.

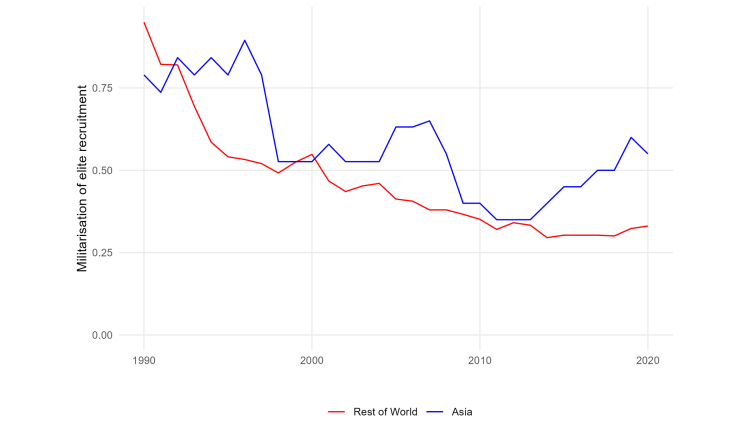

Turning first to the selection of political elites, Figure 1 below shows the average annual trends regarding military officers being recruited into top political positions in Asia compared to globally between 1990 and 2020. It highlights how the decline in military-elite recruitment that started in 1990 – namely, as a result of the interwoven effects of the third wave of democratisation spreading regionally and the Cold War coming to an end – has clearly gone into reverse since the early 2010s. Moreover, with a brief exception in 2000, Asian militaries have consistently enjoyed higher representation in their countries’ governments compared to the global average, a trend notably increasing from the 2010s.

Figure 1. Military Elites’ Recruitment into Politics in Asia and Worldwide, 1990–2020

Source: Authors’ own elaboration, based on Bayer et al. (2023b).

Note: Levels of military elites’ political recruitment recorded on a scale from 0–3, with higher scores denoting larger degrees thereof.

Of course, the aggregate data in Figure 1 masks the substantial differences existing between countries and across forms of political militarisation. First, political militarisation is on average more pronounced in Southeast Asia than elsewhere in the region. Moreover, the recent resurgence of political militarisation has especially been driven by developments in a number of autocratic or autocratising regimes such as Cambodia, Myanmar, North Korea, the Philippines, and Thailand, where the military has gained greater political influence since the 2010s. Second, the notable rise in military representation in government over the last decade is due to the increasingly prevalent practice of former or active-duty military officers becoming ministers of defence. This is common in many autocracies, such as China and Vietnam, but occurs in democracies too, like Indonesia and South Korea. In contrast, and despite exceptions in Myanmar and Thailand, the low number of military coups and military regimes throughout the post–Cold War period distinguishes the Asian region from other (re)militarising parts of the world, such as West Africa and the Sahara (Basedau 2023). Still, the aforementioned developments suggest a (re)militarisation of defence policymaking is taking place alongside civilians’ waning influence regarding the day-to-day control and oversight of the armed forces.

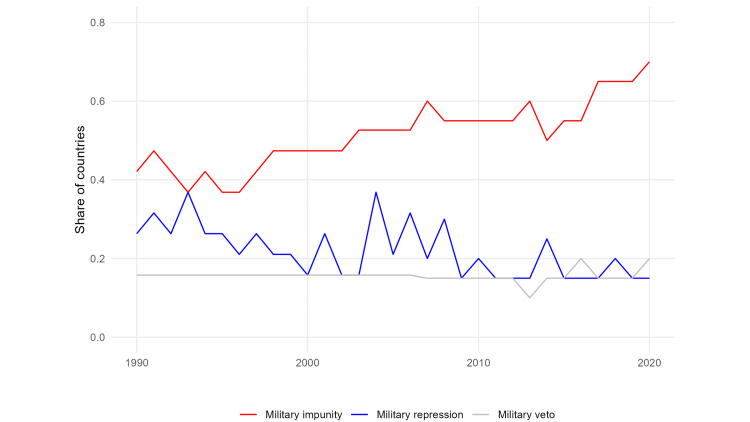

Turning to the two remaining aspects of political militarisation, Figure 2 below shows the extent of the political privileges enjoyed by the military and the rising prevalence of military repression against civilians. In 2020, for example, military leaders had informal or constitutional veto power over certain policy matters in almost 20 per cent of all Asian governments, whereas the global share was only 13.7 per cent. Moreover, in the same year, more than 60 per cent of all Asian militaries were at least partially exempt from punishment when they engaged in illegal activities, such as human rights violations, the physical abuse of citizens, corruption, or severe cases of insubordination. This is well above the global average of 54.9 per cent of all countries. The fact that impunity is on the rise indicates that military-justice reforms, where they existed, have been slow and often ineffective. On a more positive note, the military’s participation in domestic repression against unarmed civilians has declined over time, from a peak of occurring in 37 per cent of all Asian countries in 1993 and 2004, respectively, to in 15 per cent thereof in 2020. Myanmar, Pakistan, the Philippines, and Thailand were the only countries in Asia in that year in which the military simultaneously exercised political veto power and possessed substantial impunity.

Figure 2. Military Veto Power, Impunity, and Repression in Asia, 1990–2020

Source: Authors’ own elaboration, based on Bayer et al. (2023b).

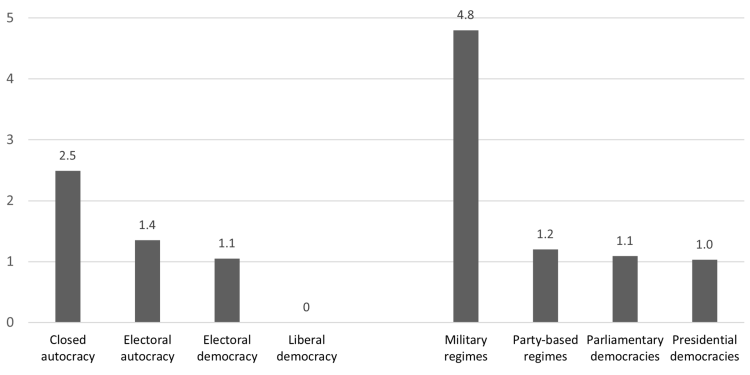

Finally, as shown in the left-hand panel of Figure 3 below, levels of militarisation in Asia also vary across regime types. Liberal democracies like Japan, Mongolia, South Korea, and Timor-Leste have been mostly spared from political militarisation. In sharp contrast, closed autocracies that ban multiparty elections and heavily restrict political rights and civil liberties are the most militarised, whereas electoral autocracies and electoral democracies find themselves somewhere in the middle.

Figure 3. Average Levels of Political Militarisation in Asia by Regime Type, 1990–2020

Sources: Authors’ own elaboration, based on data from Bayer et al. (2023b) regarding militarisation; from Coppedge et al. (2023) regarding autocracy/democracy; from Bell, Besaw, and Frank (2021) regarding regime type.

Note: Levels of political militarisation recorded on a scale from 0–6, with higher scores denoting larger degrees thereof.

The right-hand panel of Figure 3 shows the degree of political militarisation in the two main types of autocratic regimes – military versus party-based – and the two dominant institutional forms of democratic government – parliamentary versus presidential – in Asia. Unsurprisingly, political militarisation is dramatically high under military regimes. In contrast, party-based autocracies such as China, Laos, Singapore, and Vietnam are quite effective at controlling the military’s political power. This suggests that weakly institutionalised political parties enable high levels of military power and political influence, while party-based autocracies with well-institutionalised and ideologically or consensually unified ruling parties are almost as effective at reining such influence in as many democracies in the region. Interestingly, however, these striking differences between military and party autocracies contrast with the negligible differences found in levels of political militarisation across the two institutional forms of democratic rule in Asia. While the data suggests that parliamentary democracies exhibit, on average, slightly higher levels of political militarisation than their presidential counterparts, the differences are miniscule.

Material Militarisation

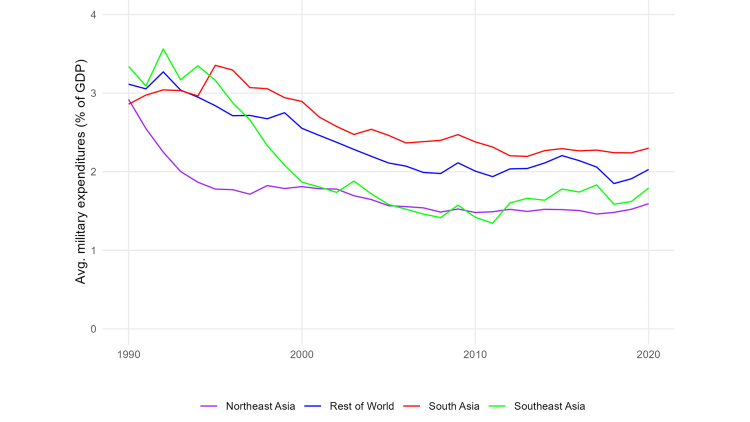

Material militarisation denotes an increasing allocation of material, social, and economic resources to the armed forces. Spending is one crucial aspect of material militarisation, personnel another. Regional dynamics regarding military spending as a percentage of gross domestic product mirror global trends, with levels hereof shrinking during the 1990s and first decade of the new century before substantially increasing since then – especially in South and Southeast Asia (see Figure 4 below). This is reflective of how India and the Southeast Asian nations have responded to China’s accelerating military modernisation and increasing naval activity in the South China Sea and beyond.

Figure 4. Military Expenditure as a Percentage of GDP, 1990–2020

Source: Authors’ own elaboration, based on Bayer et al. (2023b).

Against this backdrop, the relatively low figures for Northeast Asia are suspect. For one thing, the M3 dataset does not report military expenditure for North Korea. For another, figures for China’s military spending are highly unreliable and its defence budget is notoriously opaque. Including missing/better data would likely result in considerably higher military expenditure figures for East Asia and a stronger upwards trend than the one exhibited here.

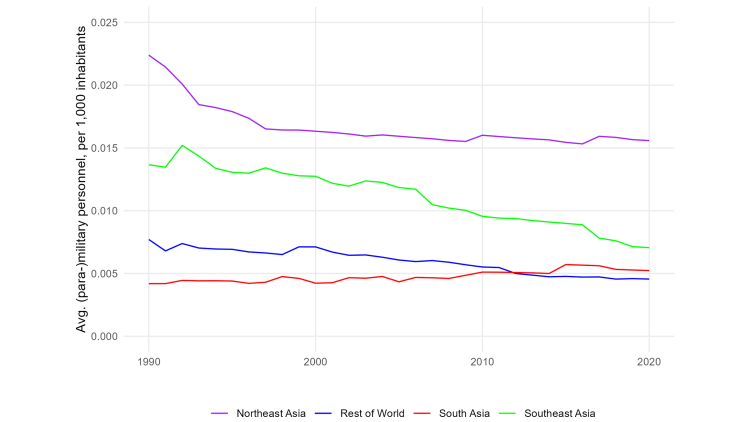

Figure 5. Military Personnel per 1,000 Inhabitants, 1990–2020

Source: Authors’ own elaboration, based on Bayer et al. (2023b).

Furthermore, the proportion of the population serving as (para)military personnel in Asia remains well above the global average, especially in Northeast and Southeast Asia. In 2020, three Southeast Asian countries (Cambodia, Laos, and Singapore) had more than 1 per cent of their population under arms, while the high numbers for East Asia are driven mainly by the deeply militarised society of North Korea. For 2020, the M3 data reports 5 per cent of the total population serving in Pyongyang’s armed forces – the highest such figure worldwide by a significant margin. In both Northeast and Southeast Asia, however, the general trend is towards declining relative troop sizes; in South Asia, contrariwise, the share of military personnel among the total population in Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan has risen since the mid-2010s, mirroring military-expenditure trends.

Societal Militarisation

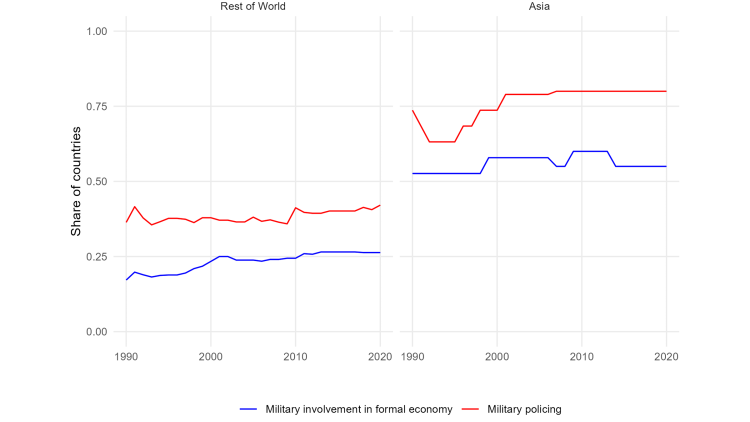

The military can also enjoy an expanded role in societal institutions and the daily life of ordinary citizens, often linked to a stronger admiration for the military. In contrast to the Global North, where the basic mandate is typically territorial defence against external threats, many Asian militaries are extensively involved in broadly defined internal missions such as state-building, economic development, and the provision of public and state security (Croissant 2018; Izadi 2022). Of particular importance in this context is the military’s involvement in policing operations such as law enforcement, peace preservation, and crime prevention. Figure 6 below compares the Asian countries to the global average over time. Military policing in Asia has been rising since the mid-1990s. Since the middle of the following decade, meanwhile, almost four out of five Asian militaries have been involved in at least some form of policing, while worldwide the share remains less than 50 per cent. In terms of subregional comparisons, military policing is particularly pronounced in South and Southeast Asia, with Indonesia, Laos, Myanmar, Pakistan, the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam routinely deploying troops to conduct a wide range of domestic security operations.

Figure 6. Share of Countries with Military Personnel Engaged in Policing and Economic Activities, 1990–2020

Source: Authors’ own elaboration, based on Bayer et al. (2023b).

In addition to internal security, Asian militaries are often deeply involved in economic and commercial activities, with sometimes wide-ranging influence here nationally. As shown in Figure 6, the military was active as an entrepreneur in 25–30 per cent of all countries worldwide between 1990 and 2020, while in the same period the proportion in Asia was twice as high. Countries with particularly strong military–business complexes include China, Indonesia, Laos, Myanmar, Pakistan, Thailand, and Vietnam.

Implications of Militarisation for Political Development and Regional Stability

These worrisome developments regarding political, material, and societal (re)militarisation in Asia may have potentially drastic consequences for socio-economic development, the quality of governance, and political stability in the region. First, preliminary statistical findings suggest that higher levels of political militarisation in the past were clearly associated with declining democratic and economic performance, as well as poor governance in subsequent years. While to achieve a better understanding of drivers, causal mechanisms, and processes linking militarisation and political and socio-economic transformation will require more research, it seems evident that the military's growing political influence undermines democratic processes, jeopardises economic performance, and fosters bad governance. Vice versa, a decline in militarisation is often followed by increases in democratic quality, economic development, and good governance. These findings are true both globally as well as for Asia.

In this context, it is important to note that autocratisation linked to a (re)militarisation of politics is not limited to countries such as Myanmar, Pakistan, or Thailand where the military has openly intervened in politics but also occurred in Bangladesh, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Sri Lanka. Moreover, militarisation below the threshold of military intervention can act as an early-warning indicator of future coups (Bayer et al. 2023a). It is therefore important to remain vigilant when looking for reasons for democratic and economic decline in Asia’s countries.

Second, in Asia especially extensive involvement in the economy often goes hand in hand with the military’s increased political power. In fact, the “khaki capitalism” of Myanmar, Pakistan, and Thailand is simply one dimension of a militarised political economy in these countries, while the armed forces’ sway over administrative structures and political networks constitutes another (Chambers and Waitoolkiat 2017). Combined, military entrepreneurship and a militarised bureaucracy provide the “deep state” with the necessary resources and capacities to penetrate and control politics and society. Examples such as Indonesia, Laos, and Vietnam demonstrate that a militarised political economy is not anathema to economic or political reform. Nonetheless, extensive military involvement in the economic arena clearly makes such reforms less likely and, once initiated, more difficult to implement. The collapse of tenuous civilian–military compromises in Myanmar, Pakistan, and Thailand highlights the immense challenges faced in seeking a comprehensive and sustainable demilitarisation of the political system in those countries where political, material, and societal militarisation have been mutually reinforcing for decades.

Further, as Roya Izadi (2022)illustrates, the military is more likely to get involved in the economy when its material interests are at risk and when political leaders depend on its coercive power to remain in office. In new and consolidating democracies, the extensive involvement of military profit-making enterprises tends to undermine civilian control (Kuehn and Croissant 2023). Economically active militaries are less inclined to support public demands for regime change and democratic reform under authoritarianism, both in Asia and elsewhere (Croissant, Eschenauer-Engler, and Kuehn forthcoming).

Finally, the militarisation of Asian states is also a concern for peace, stability, and cooperation in the region. While the relationship between militarisation and domestic or international conflict is an area of active research, existing studies suggest that higher levels of militarisation may both perpetuate existing and create new conflicts, for example diversionary wars against perceived internal or external enemies (e.g. Weeks 2008). Moreover, militarisation also runs the risk of subordinating social values to the military’s own ends (Levy 2016). The long-term after-effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, during which health risks, economic threats, and the militarisation of public health became intertwined, might further accelerate this possibility, especially in less developed countries with weak states.

Implications for Local and European Decision Makers

Throughout Asia, pervasive military involvement in politics, society, and the economy represents a deep-rooted historical pattern. Following the end of the Cold War and the arrival of democratisation in the region, nations such as Bangladesh, Myanmar, Pakistan, South Korea, and Thailand witnessed a retreat of military influence, ostensibly returning to civilian rule. However, this phase of evident demilitarisation appears to have been fleeting. Since midway through the first decade of the new century, there has been a gradual resurgence of military engagement across various segments of Asia’s societies. Military personnel are increasingly integrated into governmental roles, particularly within defence ministries, wielding significant political influence and commanding significant national resources. While the long-term repercussions of this multidimensional remilitarisation remain uncertain, historical precedent cautions against incremental militarisation in politics, society, and the economy. Such trends pose significant threats to liberal democracy, equitable socio-economic development, and regional stability.

Consequently, both local and international actors, including European decision makers, have reason to be wary of – and thus should actively work against – remilitarisation in Asia. Concretely, we propose three recommendations for action to both local and external actors here:

First, it is imperative they raise awareness regarding these ongoing militarisation trends in Asia. This increase in familiarity should encompass not only the fact that militarisation has re-emerged and accelerated as a regional phenomenon but also how it is multifaceted in nature and has political, social, and economic dimensions. Moreover, both local and external stakeholders need to be informed of the consequences and implications of unchecked militarisation for regional security as well as long-term socio-economic development. This requires active engagement in dialogue and information-sharing to better understand the complex processes and multidimensional effects of militarisation.

Second, to combat militarisation and its repercussions, stakeholders should prioritise the development of institutions and mechanisms that ensure civilian supremacy over the armed forces. This includes enhancing the transparency and accountability of the military vis-à-vis the legitimate civilian decision-making bodies, as well as greater adherence to the rule of law within military institutions. Strengthening legislative oversight, judicial-review processes, and independent watchdog agencies can help keep the military in check, thereby promoting effective governance, democratic rule, and improved economic performance.

Third, local governments need to ensure that any deployment of the military – especially in domestic security operations or in support of civilian agencies – is constitutional, limited in terms of time and scope, and based on transparent rules of engagement. The latter must be overseen by elected legislatures, the media, and civil society organisations. In the realm of democratic security operations, external stakeholders such as the European Union and international organisations can play an important and constructive role here, providing support and expertise for the civilian institutions and non-state actors that oversee military conduct. At the same time, European governments should not only advocate for responsible military practices in Asian countries but also follow the same principles of transparency, respect for human rights, and adherence to international law in their own military engagements – both in the region and across the globe.

Fußnoten

Literatur

Basedau, Matthias (2023), Coups in Africa – Why They Happen, and What Can (Not) Be Done about Them, Megatrends Afrika, 28 September, accessed 20 March 2024.

Bayer, Markus, Felix Bethke, Aurel Croissant, and Nikitas Scheeder (2023a), Back in Business or Never Out? Military Coups and Political Militarization in Sub-Sahara Africa, PRIF Blog, 28 December, accessed 20 March 2024.

Bayer, Markus, Aurel Croissant, Roya Izadi, and Nikitas Scheeder (2023b), Multidimensional Measures of Militarization (M3): A Global Dataset, in: Armed Forces & Society, first published 13 December, accessed 20 March 2024.

Bell, Curtis, Clayton Besaw, and Matthew Frank (2021), The Rulers, Elections, and Irregular Governance (REIGN) Dataset, Broomfield, CO: One Earth Future, accessed 20 March 2024.

Chambers, Paul, and Napisa Waitoolkiat (eds) (2017), Khaki Capital. The Political Economy of the Military in Southeast Asia, Copenhagen: NIAS Press.

Coppedge, Michael et al. (2023), V-Dem Codebook V13, Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project, accessed 20 March 2024.

Croissant, Aurel (2018), Civil–Military Relations in Southeast Asia, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Croissant, Aurel, Tanja Eschenauer-Engler, and David Kuehn (forthcoming), Dictators’ Endgames, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Izadi, Roya (2022), State Security or Exploitation: A Theory of Military Involvement in the Economy, in: Journal of Conflict Resolution, 66, 4–5, 729–754.

Kohn, Richard H. (2009), The Danger of Militarization in an Endless ‘War’ on Terrorism, in: The Journal of Military History, 73, 1, 177–208.

Kuehn, David, and Aurel Croissant (2023), Routes to Reform: Civil-Military Relations and Democracy in the Third Wave, Oxford Studies in Democratization, Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

Kuehn, David, Aurel Croissant, David Pion-Berlin, and Ariam Macias-Weller (2023), Military Involvement in COVID-19 Responses: Comparing Asia and Latin America, GIGA Focus Global, 3, accessed 20 March 2024.

Levy, Yagil (2016), What Is Controlled by Civilian Control of the Military? Control of the Military vs. Control of Militarization, in: Armed Forces & Society, 42, 1, 75–98.

Rudischhauser, Wolfgang (2023), The Indo-Pacific: Confidence-Building in Times of Growing Conflict Potential, GIGA Focus Asien, 6, accessed 20 March 2024.

Weeks, Jessica L. (2008), Autocratic Audience Costs: Regime Type and Signaling Resolve, in: International Organization, 62, 1, 35–64.

Redaktion GIGA Focus Asien

Lektorat GIGA Focus Asien

Regionalinstitute

Forschungsschwerpunkte

Wie man diesen Artikel zitiert

Croissant, Aurel, David Kuehn, Markus Bayer, und Nikitas Scheeder (2024), Remilitarisation in Asia: Trends and Implications, GIGA Focus Asien, 2, Hamburg: German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), https://doi.org/10.57671/gfas-24022

Impressum

Der GIGA Focus ist eine Open-Access-Publikation. Sie kann kostenfrei im Internet gelesen und heruntergeladen werden unter www.giga-hamburg.de/de/publikationen/giga-focus und darf gemäß den Bedingungen der Creative-Commons-Lizenz Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 frei vervielfältigt, verbreitet und öffentlich zugänglich gemacht werden. Dies umfasst insbesondere: korrekte Angabe der Erstveröffentlichung als GIGA Focus, keine Bearbeitung oder Kürzung.

Das German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) – Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien in Hamburg gibt Focus-Reihen zu Afrika, Asien, Lateinamerika, Nahost und zu globalen Fragen heraus. Der GIGA Focus wird vom GIGA redaktionell gestaltet. Die vertretenen Auffassungen stellen die der Autorinnen und Autoren und nicht unbedingt die des Instituts dar. Die Verfassenden sind für den Inhalt ihrer Beiträge verantwortlich. Irrtümer und Auslassungen bleiben vorbehalten. Das GIGA und die Autorinnen und Autoren haften nicht für Richtigkeit und Vollständigkeit oder für Konsequenzen, die sich aus der Nutzung der bereitgestellten Informationen ergeben.