- Startseite

- Publikationen

- GIGA Focus

- Ad Hoc Coalitions in a Changing Global Order

GIGA Focus Global

Ad Hoc Coalitions in a Changing Global Order

Nummer 4 | 2022 | ISSN: 1862-3581

Increasingly, member states of large intergovernmental organisations (IGO) are setting up ad hoc coalitions (AHC) outside of multilateral organisations at regional and global levels. What is motivating countries to circumvent traditional IGOs? Are AHCs undermining global governance institutions?

AHCs are attractive short-term instruments for crisis response among like-minded states. They often appear in the security and health sectors, though they are not limited to those areas.

AHCs are an expression of institutional adaption to the crisis of major IGOs, which are increasingly unable to create unity on pivotal global order questions.

AHCs do not pose a substantial challenge to IGOs, because they are often operational in areas in which IGOs are not willing or able to act.

AHCs are part and parcel of a wider system of crisis response. They co-govern dense institutional spaces together with IGOs and form a network of institutions responding to a crisis.

Policy Implications

German foreign policy has traditionally placed a strong emphasis on multilateral organisations as cornerstones for a rules-based international order. With the emergence of AHCs, a further instrument is available that should not be dismissed as anti-multilateral. For AHCs to make a valuable contribution to the ever more complex global governance system, they need to perform functionally different tasks from IGOs. Germany should consider actively participating in AHCs to avoid being sidelined by partner countries.

Multilateral Organisation in Crisis and Ad Hoc Coalitions

Much has been written on the current demise of the liberal global order; in fact, the erosion of traditional multilateral institutions is real (Ikkenberry 2018). Multipurpose intergovernmental organisations (IGO) face particularly significant challenges (Patrick 2015). The use of the veto within the UN Security Council is at its highest rate since the end of the Cold War, with the organisation being unable to effectively address major conflicts such as those in Syria or Ukraine. The UNSC is also doing little to ease tensions among its most potent members. Great power rivalry is a determining feature of our decade. Elements of cooperation coexist with increased competition (Prys-Hansen 2022). The European Union has lost one of its strongest member states, the UK, and continues to struggle to convert its economic power into geopolitical influence. With the Russian invasion of Ukraine major warfare returned to Europe, effectively destroying the post–Cold War security order. Negotiations on new trade agreements within the World Trade Organization (WTO) have been stalled for more than a decade. In the Global South, regional organisations often do not progress beyond initial steps of token regionalism. The COVID-19 pandemic plunged many countries into an acute medical crisis, which was followed by economic recession and a short boom but also high energy prices and increasing inflation rates. This agglomeration of major crises and their interconnections has been termed “polycrisis,” constituting a serious stress test for global and regional governance institutions (Janzwood and Homer-Dixon 2022). Naturally, in times of historic uncertainties, old truisms are challenged.

Within the existing liberal world order, large IGOs have traditionally occupied a central role as guardians and catalysts for globalisation and advancement for global governance in a rules-based order. The implicit deal between state parties providing global public goods in the form of delegation of power and resources to IGOs was that an ever more connected world is a safer and more prosperous place in which power politics is secondary to the regulative advantages global governance institutions provide. While global governance institutions have indeed contributed significantly to wealth creation and security, their performance is not unerring and is now undergoing a phase of scrutiny and adjustment.

Large multipurpose IGOs find it difficult to generate political consensus around major crises. This has been painfully clear vis-à-vis how COVID-19, the wars in Syria and Ukraine, global free trade, and the climate crisis have all been handled. The bureaucratic and rules-heavy approach of IGOs tends to complicate finding common positions. Long-lasting multilateral negotiations are no guarantee that an implementable compromise will be found. However, most IGOs are built with the expectation that deliberation will, in the end, lead to global governance improvements, providing solutions for collective action problems. But when diplomacy fails because no common ground is agreeable, IGOs reveal their dysfunctionalities. Increasingly, the often-propagated virtues of interconnectivity are seen with scepticism, if not flat-out opposition. This may be most obvious within right-wing populist movements that claim to want to “take back control” nationally – for example, by leaving the EU. While populist positions often do not stand the test of truth, the idea that connectivity can have negative consequences, including being weaponised, is now explored by an increasing number of studies (Leonard 2021). Major countries around the world are considering reducing their external dependency on critical goods such as semi-conductors, energy supplies, sovereign debt, vaccines, and 5G network infrastructure. A high degree of interconnectedness might indeed also contribute to conflict.

While we are not witnessing a total rollback or breakdown of globalisation and dissolution of its major hubs (IGOs), the current crisis of IGOs provides opportunities to rethink how global governance institutions operate and how to address the apparent impasses they are confronted with. Although IGOs face significant challenges when engaging today’s crises, this has not resulted in a passive acceptance of the status quo by the international community. There is no shortage of political activism. Instead, alternative forms of organisation emerging alongside established institutions are growing in popularity. One such innovative form comprises ad hoc coalitions (AHC). Although they are not an entirely new phenomenon, they seem to be gaining in popularity. AHCs are often used as a rapid response instrument to address an immanent crisis. Examples are not difficult to find (see Table 1). They are most prevalent in the security field but are also popular in the health sector.

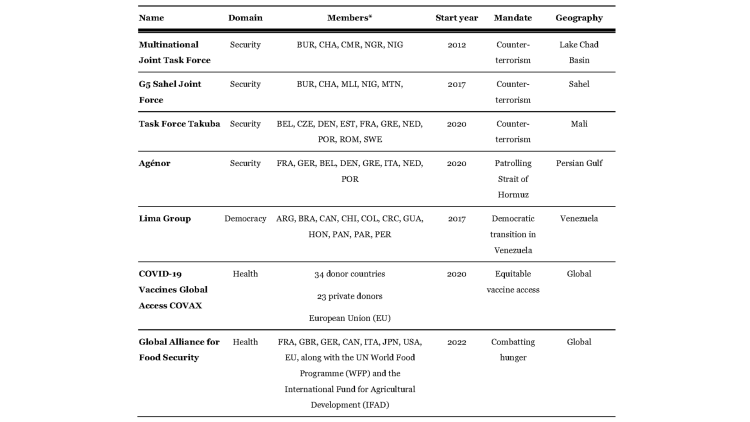

Table 1. Select List of Recent Ad Hoc Coalitions

Note: * Country abbreviations according to the International Olympic Committee.

In Africa, the fight against Islamist insurgencies has been delegated to the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF). The G5 Sahel Joint Force (G5S-JF) has been set up to counter terrorism in the Sahel. Both AHCs operate outside of the African Union’s security framework, the African Peace and Security Architecture (APSA). Likewise, a number of EU countries set up the Task Force Takuba, also operating in the Sahel, but opted not to use the EU’s structures. In South America, the autocratic regime of President Nicolás Maduro and near breakdown of state structures in Venezuela led to the establishment of the Lima Group in 2017. The group consists of 11 mostly South American countries supporting a democratic transition in Venezuela. In the health sector, the distribution of COVID-19 vaccines is not organised by the World Health Organization (WHO) but through the COVAX programme. Similarly, the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunisation (GAVI) has been set up alongside but not within the WHO. Last, the consequences of the war against Ukraine for global food supply are being addressed by the Global Alliance for Food Security (GAFS) rather than the respective UN agencies.

Countries increasingly tend to set up AHCs outside existing IGOs but in areas in which these organisations could take action. This raises a number of questions: What is the motivation to opt for an AHC, and is this trend of choosing flexible coalitions over established organisations worrisome? Is it undermining global governance institutions, or is it a sign of institutional innovation and adjustment to new challenges and in this way complementing rather than competing with established organisations?

Until now, AHCs have not been explored systematically. They are defined by three characteristics: their task-specific mandate, their short-notice creation, and their (at least initially) limited time frame (Reykers et al. 2022). Additionally, they function in dense institutional spaces that are part of a wider global governance system and tend to operate with a light bureaucratic apparatus in the background. While AHCs are not confined to only one policy area, they seem to be particularly popular in the security sector. This is not surprising, as suddenly erupting crises require responding quickly, which is easier to achieve within a smaller group of like-minded countries than within regional or global organisations. For this reason, this article focuses on security-sector AHCs.

What Makes Ad Hoc Coalitions So Attractive?

AHCs are primarily designed to deliver a specific public good within a short timeframe without engaging a heavy bureaucratic machinery. For military interventions – for example, in response to violent insurgencies – IGOs have invested significantly in various intervention instruments such as the African Standby Force (ASF) in the AU and the Battlegroups in the EU. However, in practice, these instruments turned out to be difficult to deploy. Their internal structure is based on a rigid composition of subregional groups of countries. The inherent diversity of interests makes it rather unlikely that all countries in a Standby Force operation or Battlegroup agree to deploy. Most countries tend to reject externally imposed “marching orders” to participate in a mission, favouring control over those resources they provide for an operation. This is especially true for high-risk military operations that might entail active combat. The consequence is that both the AU and EU possess the technical and institutional capability for military deployments but lack broad enough member-state support to use these instruments. The EU managed to mandate only small-scale and rather low-risk training and support missions to African conflicts, reflecting the minimum consensus achievable.

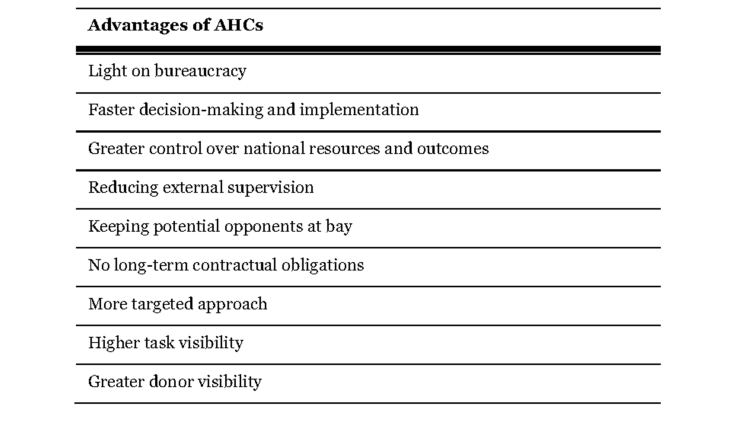

AHCs provide a seemingly better solution. They flexibly group together like-minded countries around a pertinent issue. This was seen in case of the anti-Boko Haram coalition the MNJTF, the G5S-JF, and Task Force Takuba. These smaller groups of countries have (partly) decoupled themselves from the decision-making processes of their regional patron organisations. On some occasions, they are mandated and endorsed ex-post by IGOs. AHCs guarantee participants greater control over their own national resources (troops, funding) and mission operations, allow them to circumvent potentially lengthy bureaucratic decision-making procedures, and enable them to temporarily work together without much external supervision or long-term contractual obligations. Working within the framework of an AHC also prevents potential opponents to the project from delaying or sabotaging deployments, as they are not directly involved in decision-making. For the EU, unanimity is required in foreign and security matters. In the AU, consensus decision-making, although not always formally required, is the politically preferred modus operandi, which provides spoilers with significant influence over the use of resources from other countries.

In the health sector, not working through the WHO provides donors with more direct control over their financial contributions, along with making specific tasks and projects more visible and creating public recognition for the donor. In South America, countries tend to support non-military forms of conflict management. The Lima Group supporting democratic transition in Venezuela was set up because no continent-wide agreement exists on how to engage with Maduro. In sum, AHCs have the potential to speed up the response to a crisis by maintaining near full control over operations in a clearly demarcated area on a temporary basis. This option appears attractive for certain countries, such as regional powers, when comparing it to the alternative path of using an established IGO. In this context, regional powers tend to initiate the establishment of AHCs and lobby neighbouring countries to join their initiatives. This was seen in the case of Nigeria and the MNJTF, and France with Task Force Takuba and Operation Agénor.

Table 2. Advantages of AHCs from the State Perspective

Do Ad Hoc Coalitions Fragment or Complement?

Given the current debate around a deepening crisis of multilateralism, one may well argue that AHCs are contributing to it as they seemingly undermine IGOs. In fact, once an AHC has been set up it is unlikely that an IGO will enter the scene and duplicate efforts. In this sense, a once-occupied functional space is difficult to regain. Even if IGOs are not weakened substantially, they are forced to operate in dense institutional spaces, which limits the relevance of single organisations. AHCs are hardly restructuring the operational territory of IGOs in an all-encompassing way. However, the emergence of AHCs certainly signals a shift in focality for IGOs within the wider global governance system: IGOs are no longer the only focal points of global governance.

In order to assess if AHCs are competing with IGOs, it matters to what extent they are functionally similar or different. If AHCs are functionally different from IGOs, institutional competition is less likely to occur. If they duplicate existing structures, it is a potential case of competition. A quick look at the MNJTF, G5S-JF, and Task Force Takuba reveals that these institutions are providing functions that neither the AU nor EU or UN are able or willing to provide. These three AHCs are combat-oriented missions designed to counter various forms of insurgencies. This kind of mission mostly falls outside the traditional field of operation for the three aforementioned organisations.

EU military operations mostly consist of training missions deployed alongside larger UN peacekeeping operations. These EU missions are not designed to actively engage in combat and occupy functional niches left by other actors (Brosig 2014). These operations are also rather small, consisting of just a few hundred troops, and would not have been deployed without a larger UN or AU mission in the background. This type of EU operation reflects upon what member states are willing to agree on: low-risk, small-scale technical support and training operations. In other words, high-risk combat missions are not part of the EU’s toolbox.

Although the EU is technically able to deploy combat-oriented missions, it is politically not viable. Task Force Takuba, which was a French-led operation in Mali, was functionally different from what the EU is typically able to carry out. In this sense, Takuba did not directly undermine the EU’s foreign and security policy. However, it revealed the EU’s institutional deficits: EU countries frequently operating outside EU frameworks would shed a poor light on these structures. However, the short-term character of Takuba (2020–2022) is not a substantial challenge to the EU nor did it replace existing missions in the same region. Likewise, the UN traditionally does not deploy pure combat operations on its own. Its peacekeeping doctrine requires that the host nation consent, force be used only in self-defence, and the UN remain politically neutral.

The cases of the MNJTF and G5S-JF are similar. The design structure of the APSA does not provide a good fit for conflicts the MNJTF and G5S-JF are addressing: The APSA is built on five regional economic communities (REC). However, neither the Boko Haram insurgency nor armed conflict in Mali neatly falls into either Western or Central Africa, which would each be expected to take regional leadership with their ASF contingents. Furthermore, while the ASFs are technically operational and could be deployed, their rapid deployment capability is their least developed component and their deployment scenarios are outdated. Additionally, the AU interim mechanism, called African Capacity for Immediate Response to Crises (ACIRC), which was explicitly designed as a rapid response tool at the continental level, did not have enough support from key African countries and was not operational at the time it was needed. Nigeria never supported the ACIRC and thus it was not available in the fight against Boko Haram. In the end, the MNJTF and G5S-JF are not directly competing with the APSA, as the AU’s security structure was not in the position to perform the tasks the AHCs are performing.

Still, an element of competition is undeniable. Resources made available by countries for one instrument are not available for another. Especially resource-scarce countries are not in the position to actively participate in multiple military initiatives at the same time, and therefore need to make selective contributions. In this sense, the APSA, which was designed as the “go-to” organisation for issues of peace and security, is losing some of its centrality and member-state capacity. However, AHCs mainly occupy a functional niche that IGOs are not able to fill. In this regard, they are mostly complementary to traditional institutions.

Towards a System Response to Crisis

Key to the understanding of the effects of AHCs is their position in the wider network of relevant actors. Global governance is mostly taking place in dense institutional spaces. This means AHCs and IGOs are not working in isolation from each other but are interconnected. For example, in the context of armed conflict in Africa the list of international response mechanisms is fairly long, ranging from subregional and regional African institutions to cross-regional engagement with the EU and finally global engagement on the part of the UN. Given this high actor density, the individual institution becomes less critical in the larger frame of the entire system. Within the African context, one can speak about an African security regime complex encompassing all those institutional actors that respond to a crisis (Brosig 2013). In this environment, the question of whether AHCs are a threat to IGOs is of lesser importance as long as they are part of a system response involving several institutions.

In fact, AHCs and IGOs are linked in multiple ways. Not only can we observe membership overlap, IGOs often assume a mandating and authorisation role for AHCs. Although the MNJTF and G5S-JF are not officially integrated into the APSA, they are authorised and mandated by the AU and in some cases also the UN. IGOs lend important political legitimacy that small coalitions cannot provide. Peace enforcement operations on their own often cannot achieve a lasting peace. Political and economic grievances contributing to armed conflict are mostly not addressed by the MNJTF, G5S-JF, or Task Force Takuba. Especially in the Sahel, single military initiatives operate alongside a high number of other political and development-oriented programmes run by the UN, EU, or African RECs. As long as functional differentiation exists, institutional competition is less likely to occur.

Trending Up

The trend towards using more AHCs seems to be a stable one and is most visible in the security sector. The EU’s European Peace Facility adopted in March 2021 now allows for direct funding of AHCs, and the EU’s Strategic Compass also refers to them. AHCs are a challenge for German foreign policy, but they can also be a burden-sharing instrument. European AHCs of military character are in a potential conflict with the German Constitution, which foresees Germany acting only within a “system of mutual collective security” (Art 24) (Tull 2022). Whether a given AHC falls within this category is not always clear: their short-term character and select membership might not qualify them as a collective system. Insisting on acting only through IGOs (EU, NATO, OSCE, UN, etc.) might isolate Germany from key partners willing to act through AHCs and does not necessarily help in overcoming internal institutional inertia, for example in the EU. However, Germany also profits from AHCs directly. Its largest UN deployment is currently in Mali, whose mandate overlaps with those of the G5S-JF and Task Force Takuba. Here, AHCs fulfil a burden-sharing task. Germany, with its strong emphasis on multilateralism in global governance institutions, needs to invest more in making traditional IGOs work – one instrument to this end indeed comprises AHCs, which are part of a system crisis response and operate in a functional niche.

Fußnoten

References

Brosig, Malte (2014), EU Peacekeeping in Africa: From Niche Selection to Interlocking Security Governance, in: International Peacekeeping, 21, 1, 74–90.

Brosig, Malte (2013), The African Security Regime Complex: Exploring Converging Actors and Policies, in: African Security, 6, 3–4, 171–190.

Ikkenberry, John (2018), The End of the Liberal Order?, in: International Affairs, 94, 1, 7–23.

Janzwood, Scott, and Thomas Homer-Dixon (2022), What Is a Global Polycrisis? And How Is It Different from a Systemic Risk?, Discussion Paper 2022–4, Cascade Institute, accessed 28 September 2022.

Leonard, Mark (2021), The Age of Unpeace: How Connectivity Causes Conflict, London: Pinguin Press.

Patrick, Stewart (2015), Multilateralism a la Carte: The New World of Global Governance, Valdai Papers, 22 July, accessed 28 September 2022.

Prys-Hansen, Miriam (2022), Competition and Cooperation: India and China in the Global Climate Regime, GIGA Focus Asia, 4, accessed 28 September 2022.

Reykers, Yf, John Karlsrud, Malte Brosig, Stephanie Hofmann, Cristiana Maglia, and Pernille Rieker (2022), Ad Hoc Coalitions in Global Governance: A Conceptual Framework, Paper prepared for the ECPR Joint Sessions Workshop “Complex Global Governance: Actors, Institutions, and Strategies”, Edinburgh, 19–22 April 2022.

Tull, Denis M. (2022), Ad-hoc-Koalitionen in Europa. Der Sahel als Katalysator europäischer Sicherheitspolitik?, SWP Studie 8, Berlin: SWP.

Gesamtredaktion GIGA Focus

Redaktion GIGA Focus Global

Lektorat GIGA Focus Global

Regionalinstitute

Forschungsschwerpunkte

Wie man diesen Artikel zitiert

Brosig, Malte (2022), Ad Hoc Coalitions in a Changing Global Order, GIGA Focus Global, 4, Hamburg: German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), https://doi.org/10.57671/gfgl-22042

Impressum

Der GIGA Focus ist eine Open-Access-Publikation. Sie kann kostenfrei im Internet gelesen und heruntergeladen werden unter www.giga-hamburg.de/de/publikationen/giga-focus und darf gemäß den Bedingungen der Creative-Commons-Lizenz Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 frei vervielfältigt, verbreitet und öffentlich zugänglich gemacht werden. Dies umfasst insbesondere: korrekte Angabe der Erstveröffentlichung als GIGA Focus, keine Bearbeitung oder Kürzung.

Das German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) – Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien in Hamburg gibt Focus-Reihen zu Afrika, Asien, Lateinamerika, Nahost und zu globalen Fragen heraus. Der GIGA Focus wird vom GIGA redaktionell gestaltet. Die vertretenen Auffassungen stellen die der Autorinnen und Autoren und nicht unbedingt die des Instituts dar. Die Verfassenden sind für den Inhalt ihrer Beiträge verantwortlich. Irrtümer und Auslassungen bleiben vorbehalten. Das GIGA und die Autorinnen und Autoren haften nicht für Richtigkeit und Vollständigkeit oder für Konsequenzen, die sich aus der Nutzung der bereitgestellten Informationen ergeben.