- Home

- Publications

- GIGA Focus

- Structural Reform in the Arab Gulf States – Limited Influence of the G20

GIGA Focus Middle East

Structural Reform in the Arab Gulf States – Limited Influence of the G20

Number 3 | 2017 | ISSN: 1862-3611

Since summer 2014, the drop in world oil prices has left holes in the budgets of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) members. Thus, in addition to privatising state-owned enterprises, these governments plan to introduce taxation for the first time ever. From the beginning of 2018, a value added tax of 5 per cent will be levied in all six Gulf monarchies. However, systematic taxation has far-reaching consequences: in the Gulf, for instance, citizens have hitherto enjoyed tax exemption and high subsidies but could demand political participation as taxpayers. The G20’s influence on these reforms is above all symbolic in nature.

Even optimistic predictions do not anticipate the price of oil returning to the level of USD 110 per barrel, which it reached in June 2014. That presents the oil monarchies in the Gulf with enormous challenges. The majority of them spend far more than they earn through the sale of hydrocarbon products.

Up to now, the Gulf States have reacted to their growing budget deficits by cutting spending, falling back on financial reserves, reforming taxes, and privatising state-owned enterprises.

Taxation requires a reciprocal relationship between a government and its citizens, but the expansion of representative institutions is not a real political option in the Gulf. Instead, the oil-rich authoritarian monarchies will attempt to develop other forms of governance services – such as, enhanced digitalisation, the creation of friend–foe schemes, and the accentuation of the global exclusivity of their own citizens.

Policy Implications

As the most influential member within the GCC and the only absolute monarchy within the G20, Saudi Arabia will assertively canvass support from among the 20 most powerful countries in the world for its planned structural reforms. However, any support for Saudi reform and regional policy at the G20 summit in Germany in July 2017 should depend on its policies meeting two requirements: respect for the fundamental principles of human rights and international law and the integrative involvement of all relevant states in the region.

The six member states of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) are currently facing far-reaching economic and political challenges. The long-term prospects for the world energy markets mean that a differentiation of the state revenues systems in the Gulf is urgently required, as these systems are exclusively based on the hydrocarbon sector. In addition to higher rates of debt – which will soon be inevitable in financing a transition phase – tax system reform will have to play a key role in ensuring fiscal stability. Thus, it should be a G20 objective to support the GCC member states, which are of key importance for the stability of the Middle East, to successfully implement their pending structural reforms.

However, such support should not be given at any price. As the most influential actor in the GCC and as a member of the G20, Saudi Arabia will use the opportunity of the G20 summit in Hamburg in July to not only promote its reform proposals but also intensely search for investors from among the world’s largest economies for its ambitious privatisation programme. Saudi Arabia, an absolute monarchy, has come to understand that in a globalised world authoritarian leaders depend on acceptance and allies. Next to investment capital, regional stability represents the most important commodity – something the Gulf States, headed by Saudi Arabia, can offer. The influence of the G20 on the Gulf monarchies concrete reform proposals will, however, be limited. Nevertheless, the G20 must continue to demand compliance with fundamental human rights and international law as well as the involvement of all regional powers. Both elements are essential to the success of structural reforms within the framework of future GCC regional and adaptation policies.

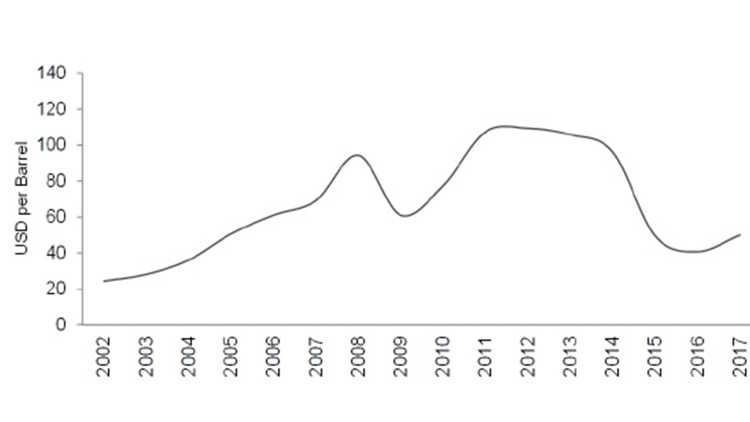

The Decline in World Oil Prices since 2014 and the Fiscal Consequences for the Gulf Monarchies

On 23 June 2014 a barrel of crude oil (about 159 litres) was still being traded at a price of USD 111.18 at the futures exchange in Dubai. By the end of the 2014, the price had dropped to USD 53.76 per barrel – meaning that the most important income source of the six GCC member states had seen its value halved in just six months. Since then, the price of oil has levelled out at an average price of around USD 50 per barrel (see figure 1). This development has had wide-reaching economic, social, and possibly even political consequences for the authoritarian Gulf monarchies.

All GCC member states greatly profited from rising oil prices that began during the middle of the first decade of the twenty-first century. The high oil prices between 2010 and mid-2014 were historic. As a result, high surpluses benefitted the national budget, and growth figures were markedly good. Many governments began to invest heavily in infrastructure and prestige projects. They were also able to build up their foreign exchange reserves, and many Gulf States arranged global investments. But as a consequence of the Arab Spring, the costs of subsidies and the public sector have increased since 2011. Because the majority of citizens in the Gulf monarchies are employed in the public sector, their salaries were increased, and new positions were created within the security sector and the state bureaucracy. The goal was to provide the younger generation of citizens with employment and decent wages (Lucas und Richter 2012). The elites also wanted to avoid mass protests against the authoritarian regimes – similar to those that occurred in Tunisia in December 2010 and in Egypt and Bahrain in January 2011 – by all means. Without the high revenue generated by the sale of hydrocarbon products, the authoritarian Gulf monarchies would not have survived the Arab Spring so easily. With the exception of Bahrain, they mostly (apart from short-lived or specific minority-led protests in Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and Oman) or completely, as in the case of Qatar and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), escaped the impacts of the Arab Spring.

The beginning of the drop in oil prices in the summer of 2014 hit the six GCC countries during a politically sensitive situation. The weight of the fiscal burden that was incurred is illustrated in table 1 by the countries’ respective break-even oil prices – a notional price on which the national budget is theoretically balanced.

Since 2014, the break-even oil prices for Bahrain, Oman, and Saudi Arabia have far surpassed the actual oil price. Despite the introduction of effective saving measures (no later than in 2015), this difference is still visible in all three countries. Even the UAE and Qatar were forced to take a series of measures to adjust their break-even oil prices to the actual price. Only Kuwait, due to its extraordinarily high production volume per capita, did not have to take on any debt despite an oil price level of around USD 50 per barrel. The consequences thereof can be seen in the budget balance, debt ratio, and foreign exchange reserve figures as a percent of gross domestic product (GDP) (see table 2).

In Qatar, the UAE, and Kuwait the discrepancy between state revenue and expenditure has remained at a relatively low, negative level. In fact, Kuwait is expecting a small budget surplus for 2017. In the UAE and Kuwait the debt ratio is small, whereas in Qatar it is around 50 per cent of GDP. All three countries have sufficient foreign exchange reserves to provide them with a degree of room for manoeuvre in relation to the budget deficit. In contrast, since 2015, the budgets of Bahrain, Oman, and Saudi Arabia have exhibited a high deficit of over 10 per cent of GDP; though this development is proceeding most dramatically in Bahrain. Along with the country’s perpetually high budget deficit, the debt ratio has increased to over 80 per cent of GDP. At the same time, foreign exchange reserves have melted away since 2014. Based on current levels, Bahrain can no longer cover its budget gap with reserves it has available. Although Oman has had a budget deficit similar to that of Bahrain since 2014, the structural conditions in the sultanate have proven more advantageous. There, the debt ratio is rather low at around 35 per cent, and foreign exchange reserves account for about a third of current GDP. In contrast, Saudi Arabia represents a special case: even though its budget deficit was over 15 per cent in both 2015 and 2016, its debt ratio was registered as being the lowest of all the GCC members. In addition, during the oil-price boom, Saudi Arabia stockpiled historically large foreign exchange reserves, which will enable it to offset its current budget deficit level over a number of years.

For the GCC states, there are – in principle – three ways to react to the sinking world oil price:

Stabilise oil prices, which would ideally lead to a new hike

Reduce government spending parallel to decreasing government revenue

Fill the budget gap in the national budget by raising and implementing alternative revenue sources.

Stabilising the Oil Price

For the authoritarian Gulf monarchies, influencing oil prices so that they climb back to a higher level is an attractive target. Increased state revenues could ease the pressure for reform in the respective societies. However, influencing crude oil prices in the international market is a complex task, if not an impossible one. In such a case, Saudi Arabia would take on a central role due to its traditional function as the global swing-producer.

Since summer 2014, Saudi policy has seemingly been focused on riding out the threatening low-price phase in the oil market. Up to the death of King Abdullah in January 2015, Saudi Arabia had made no serious efforts to soften or even impede the decline in oil prices. Following the 166th OPEC Meeting in Vienna in November 2014, no production cuts were announced. On the contrary, OPEC members – with Saudi Arabia at the head – expanded production. In this initial phase, Riyadh was more concerned with defending its market share in the global oil market and, indirectly, the shares of the other GCC members (Claes et al. 2015). Following King Salman's succession to the throne and his decision to rearrange the line of succession in favour of his nephew Mohammed bin Nayef (crown prince) and his favourite son Mohammed bin Salman (deputy crown prince), Saudi Arabia's strategy with regard to world oil prices began to change. However, it was not until the beginning of 2016 that any publicly discernible efforts were made to stabilise the threat of continued drops in oil prices through collective action by the oil producers. Not least because of the ever-increasing rivalry between the Saudi royal family and the Iranian leadership, an agreement between the oil producers was delayed until the end of 2016. At the 171st OPEC Meeting in November 2016, a six-month restriction on production was announced for the first time; days later, 11 non-OPEC countries, including Russia, followed suit (MEES 2017). As a result, oil prices went up by a few dollars per barrel. A nine-month extension of the agreement (until March 2018) was announced in May 2017.

However, whether this agreement will serve as an impulse for a long-term increase in oil prices far in excess of USD 50 per barrel is questionable. The main reason for this lies with the adaptability of the unconventional oil industry, which extracts hydrocarbon products through fracking mainly in the United States and increasingly in other world regions. Even experts have been surprised at how quickly companies operating in the US market have succeeded in reducing their production costs since 2014. This segment of the world market already started to increase its production volume in autumn 2016 (Mahdi et al. 2017). Currently, the unconventional oil industry in the United States can make a profit while producing at a level of USD 43–USD 45 per barrel (AFP 2017). Due to its almost exclusively private ownership structure, this segment of the world market is unlikely to be integrated into the new, state enterprise–dominated cartel, OPEC Plus.

Long-term, there have been a number of additional developments that make it unlikely that oil prices will return to summer 2014 levels. This includes the trend towards e-mobility in several industrialised countries and the political goal to expand renewable energy in Germany, in particular, and several other Western European countries. Thanks to global climate protection efforts (UN Climate Conference, Paris, 2015), there is a worldwide trend towards decarbonisation – that is, the significant reduction of carbon emissions, which will be unstoppable in the long run. Consequently, the GCC countries’ efforts to bring about a significant rise in the price of oil represent a drop in the ocean and are very likely to fail in the medium term.

National Adaptation Strategies for Sinking Oil Prices

In contrast to the efforts to influence world oil prices, measures that target a reduction in expenditure and the development of new state revenues are more realistic options for the Gulf monarchies. Although the experiences of previous low-price phases have shown that cuts to state benefits are likely to prompt social opposition, national adaption strategies – in comparison to international policies – have the clear advantage of enabling the respective state to deal with this using its own scope for action. The majority of GCC countries recognised this scope and introduced a number of reforms.

Simply put, due to the decline in oil prices, the following adjustments have been made since 2015:

Investments in infrastructural and prestige projects have been postponed or adjusted

Fuel, water, and energy subsidies and other public services have been cancelled

Existing taxes and fees have been expanded and/or increased

States have engaged in new borrowing in national and international credit markets.

State-owned enterprises have been privatised

Existing forms of taxation have been reformed and new ones have been introduced.

The specific mix of these political measures varies from country to country, but they arise out of the following country-specific aspects: the level of oil revenues and the national debt, the commitment to reform of central decision-makers, and the degree of social polarisation.

A first fiscal measure has been to reduce investments in initiated large-scale projects or to defer the start of new projects – both of which can be implemented without sparking public opposition. Notable examples are the postponement of the GCC-wide rail network, the delay to construction of the culture and tourism island (Saadiyat) in Abu Dhabi, and the sluggish progress in completing the King Abdullah financial district in Riyadh. A second measure, which was relatively quickly announced during 2015 and implemented in all GCC member states by 2016, was the marked reduction in fuel, energy, and water subsidies. For instance, having previously had some of the lowest petrol prices worldwide, Kuwait raised the price of petrol in 2015 and 2016 by over 100 per cent; Saudi Arabia, by up to 200 per cent (Krane and Hung 2016). A third measure has seen many Gulf monarchies not only borrow within national banking systems but also sell government bonds in international capital markets for the first time in decades. A fourth measure saw plans to privatise state-owned enterprises made public. The most prominent example, which occurred in the context of the Saudi reform programme Vision 2030, was the publication on the plan to make 5 per cent of the Saudi oil giant Aramco available to international investors. There are also concrete plans in Oman (Oman Oil Company), the UAE (Emirates Global Aluminium), and Kuwait (Az-Zour North Independent Water & Power Project) to privatise state-owned enterprises, at least partially. As a fifth measure, the governments of all six GCC members have raised fees for public services, though these by and large exclusively apply to migrant workers. However, several states are even considering introducing new duties and taxes – which, for the Gulf monarchies, would be equivalent to a revolution. In December 2016 it was announced that a uniform value added tax of 5 per cent would be implemented across all GCC states from 1 January 2018. So far, Oman is the only GCC country to have additionally increased company taxation (from 13 per cent to 15 per cent) and introduced a tax rate for micro-enterprises (3 per cent). Both measures are also to be implemented on 1 January 2018. Until now, individual income taxation has been categorically ruled out, especially in Saudi Arabia. However, there have been discussions even in Riyadh about the introduction of additional taxes and duties.

The Need for Tax Reform and Its Consequences

Apart from the payment of zakat – the mandatory contribution in Islam to those in need – there is no taxation on personal income, assets, or corporate gains in the authoritarian Gulf monarchies. Outside of the hydrocarbon sector, only foreign-owned businesses are levied with a 10 per cent–20 per cent tax on profits made. And only for oil and gas companies is there uniform corporate taxation (with the exception of Oman, which uses more general corporate taxation) which does not distinguish between domestic and foreign owners. Save for imports (which are subject to a GCC uniform duty rate of 5 per cent), as a general rule no form of goods movement or goods production is taxed (IMF 2016) – though a few exceptions apply to the tourism sector. As a result, the Gulf monarchies have to date served as unique tax havens, whose exclusivity for their respective citizens is under threat due to the drop in oil prices.

Because world oil prices are unlikely to climb back up to the summer 2014 level, it is essential – from a fiscal perspective – that the GCC member states are able to fall back on a source of income independent of hydrocarbon production in order to be able to maintain existing levels of government expenditure. Should the corresponding reform not succeed, there would likely be a phase of rising debt with an uncertain outcome for each country’s economic development and social cohesion. Therefore, in contrast to the 1980s and 1990s, the reform and introduction of tax systems is currently being discussed within the Arab Gulf monarchies.

The concept of taxation, as it developed particularly in Europe and the United States between the seventeenth century and the nineteenth century, assumes a reciprocal relationship between the tax-paying citizens and the recipient of taxes (i.e. the state). In short, in their search for additional resources, the European monarchies were prepared to share their up-to-that-point absolute political power with other societal actors. Political scientists consider this historical conflict to have laid the foundations for representative institutions, which ultimately ensured that taxes received would later be appropriately distributed and used by the crown (Ross 2004).

Following the increase in fees or, at the latest, the introduction of new taxes, the Gulf monarchies – which have historically relied on a mix of religious and traditional legitimacy, on the one hand, and the distribution of state welfare benefits, on the other – must at some point also face this new reciprocity. It will be interesting to see which solutions the governments of the GCC member states use in the future to make a case to their citizens about the benefit of taxation. The expectation that new representative institutions (e.g. parliaments) that limit the power of the ruling families will be established, or that the rights of existing advisory bodies will be extended is, however, unrealistic. None of the Gulf monarchs have any serious interest in relinquishing or sharing power. The fiscal plight in those states is not yet severe enough to make it necessary for their authoritarian rulers to grant political concessions to other societal actors in exchange for resources.

Of greater interest are the debates about old and new forms of governance services[3] within the GCC. In this context, a number of interesting observations can be made, which provide evidence about how the Gulf rulers may attempt to legitimise greater taxation of their societies. Three elements stand out:

emphasis on the improvement of traditional public services through greater digitalisation and the containment of corruption and cronyism

accentuation of the government’s achievements in protecting against external threats through friend–foe schemes (e.g. the already advanced polarisation of political discourse in Bahrain and the expansion of anti-Iranian propaganda by Saudi Arabia and the UAE)

the targeted construction of global recognition, on the one hand, and country specific exclusivity through a ruling family–dominated state (e.g. in the UAE, Qatar, and to a lesser degree Bahrain this was created by, for instance, luxurious and globally advertised urban development, the holding of mega-events, and almost completely visa-free global mobility).

Limited Opportunities to Influence for the G20

Due to its role as host of the G20 summit in Hamburg in 2017, Germany will have a key role in recognising and evaluating the importance of GCC states (Narlikar 2017). However, the G20’s opportunities to influence the numerous and far-reaching reforms planned for the Gulf monarchies will be limited, especially since the common approach of the 20 most important industrialised and emerging countries concentrates on very few general points where structural adjustment and tax reform issues are concerned. However, courting the authoritarian Gulf monarchies, as demonstrated by President Donald Trump during his recent visit to Riyadh, is inappropriate and also counterproductive for the stable development of the Gulf region. Thus within the framework of the G20 summit, it should be made clear that the pending reforms must satisfy two important requirements. First, they must observe global standards of religious, ethnic, and sexual tolerance; universal human rights; and the freedom of speech and of the press. In this regard, however, the few reports on the current approach of the Saudi security forces in Awamiyah, a village inhabited predominantly by Shiites in the eastern Saudi province of Al-Qatif, are extremely alarming. Should evidence of human rights or international law violations in relation to the situation there become available before the G20 summit commences in Hamburg in July 2017, it must be addressed by the host nation Germany. Despite Saudi Arabia’s strategic importance, the following important issues have to be raised: shortcomings made public by non-governmental organisations in the area of human rights and press freedom domestically as well as war crimes carried out by Saudi forces and confederates in Yemen.

Second, a renegotiation of globalisation can only take place once all powers in every world region are adequately involved. Thus, in the Middle East it is both sensible and necessary to establish a cooperation with Iran. Black-and-white approaches will not be conducive to achieving goals in this context; on the contrary, they would be counterproductive in the medium term and long term. Therefore, it is important that G20 members make it clear to their fellow member Saudi Arabia that a true regional power – alongside military and economic strength – must first and foremost set a normative and institutional agenda that is capable of having an integrative effect on all relevant powers in the region (Richter 2014). If cooperative interaction in the Middle East between Saudi Arabia and Iran cannot be worked out, a new level of military escalation with far-reaching political and global economic consequences threatens (Heibach 2017). Due to the key strategic position of the Gulf States to the global economy – the central trade routes between Asia and Europe pass through the region – a heightening of tensions in the Gulf would only negatively influence a reform of globalisation.

Footnotes

References

AFP (2017), US Oil Output Back Near Records, Challenging OPEC, www.yahoo.com/news/us-oil-output-back-near-records-challenging-opec-053951236.html (21 May 2017).

Claes, Dag Harald, Andreas Goldthau and Dag Harald Claes Livingston Andreas Goldthau, David (2015), Saudi Arabia and the Shifting Geoeconomics of Oil, in: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, http://carnegieendowment.org/2015/05/21/saudi-arabia-and-shifting-geoeconomics-of-oil-pub-60169 (20 May 2017).

Herb, Michael (2014), The Wages of Oil: Parliaments and Economic Development in Kuwait and the UAE, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

IMF (2016), Diversifying Government Revenue in the GCC: Next Steps, International Monetary Fund, www.imf.org/external/np/pp/eng/2016/102616.pdf (5 May 2017).

Krane, Jim, and Shih Yu Hung (2016), Energy Subsidy Reform in the Persian Gulf: The End of the Big Oil Giveaway, Issue Brief, Houston, TX: Rice’s University Baker Institute for Public Policy, www.bakerinstitute.org/media/files/research_document/0e7a6eb7/BI-Brief-042816-CES_GulfSubsidy.pdf (6 May 2017).

Lucas, Viola, and Thomas Richter (2012), Arbeitsmarktpolitik am Golf: Herrschaftssicherung nach dem „Arabischen Frühling“, GIGA Focus Nahost, 12, 1–8, http://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/handle/document/33753 (28 April 2017).

Mahdi, Wael, Angelina Rascouet and Grant Smith (2017), OPEC Keeps Focus on Shale Threat as Officials Meet in Vienna, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-05-19/opec-keeps-focus-on-shale-threat-as-officials-gather-in-vienna (19 May 2017).

MEES (2017), Opec Starts Cutting From Record Annual High, 60, 1, 7–8.

Narlikar, Amrita (2017), Kann die G20 die Globalisierung sichern?, GIGA Focus Global, 1, 1–8, https://www.giga-hamburg.de/de/publikation/kann-die-g20-die-globalisierung-sichern (21 May 2017).

Ross, Michael (2004), Does Taxation Lead to Representation?, in: British Journal of Political Science, 34, 2, 229–249.

General Editor GIGA Focus

Editor GIGA Focus Middle East

Editorial Department GIGA Focus Middle East

Regional Institutes

Research Programmes

How to cite this article

Richter, Thomas (2017), Structural Reform in the Arab Gulf States – Limited Influence of the G20, GIGA Focus Middle East, 3, Hamburg: German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-52146-4

Imprint

The GIGA Focus is an Open Access publication and can be read on the Internet and downloaded free of charge at www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publications/giga-focus. According to the conditions of the Creative-Commons license Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0, this publication may be freely duplicated, circulated, and made accessible to the public. The particular conditions include the correct indication of the initial publication as GIGA Focus and no changes in or abbreviation of texts.

The German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) – Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien in Hamburg publishes the Focus series on Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and global issues. The GIGA Focus is edited and published by the GIGA. The views and opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the institute. Authors alone are responsible for the content of their articles. GIGA and the authors cannot be held liable for any errors and omissions, or for any consequences arising from the use of the information provided.