- Home

- Publications

- GIGA Focus

- Latin America’s Search for Security: Between Repression and Dialogue

GIGA Focus Latin America

Latin America’s Search for Security: Between Repression and Dialogue

Number 3 | 2023 | ISSN: 1862-3573

The assassination of Ecuadorean presidential candidate Fernando Villavicencio has brought violence in Latin America back to the fore. It also revealed the close relationship between criminal and political violence. While “iron fist” policies may be attractive to voters, they alone will not achieve sustainable security.

Latin America leads global statistics on homicide and crime, as well as those regarding the world’s most violent cities and highest levels of violence against social activists and human rights defenders. The recent steep increase in violence in Ecuador shows that the phenomenon is not static but changes over time and place.

Violence is driven by the interaction of structural weaknesses – such as social inequality, weak state capacity, and low trust in institutions – with global shifts in organised crime.

Latin American security politics lack a focus on prevention and continuity. Instead, they meander between repression through “iron fist” approaches and attempts to disarm and demobilise criminal organisations via dialogue processes.

Punitive populism in the style of El Salvador’s President Nayib Bukele promises quick solutions, which can make it hugely popular even though it erodes democratic-governance norms and sacrifices human rights. Alternative approaches aiming to bring non-state armed actors under the rule of law via talks and ceasefires are often highly contested and need time for results to manifest.

Policy Implications

Comprehensive and long-term policies must include the de-legitimisation of the use of violence and the reduction of social inequalities. Further necessary elements are reforms of the security sector, working to overcome impunity for state and non-state actors, and the prioritisation of the rule of law and human rights. Disarmament and demobilisation processes must be conducted with transparency, monitoring, and the involvement of civil society to build legitimacy and acceptance.

Manifestations of Violence

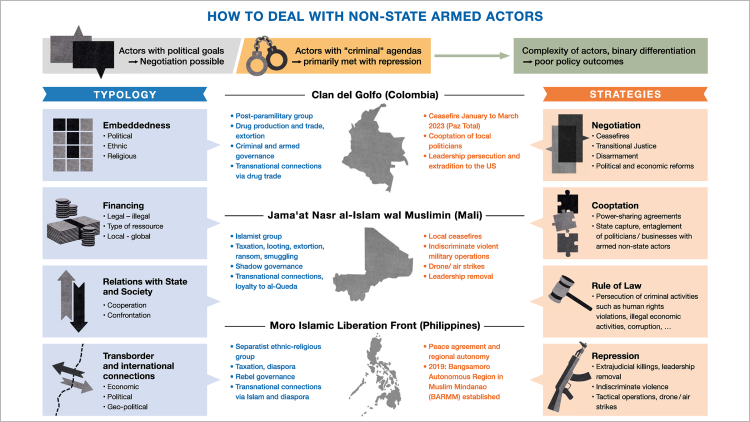

Latin America is no longer a hotspot of war and armed conflict, yet other manifestations of violence persist. While these are mostly labelled “criminal,” the assassination of Ecuadorian presidential candidate Fernando Villavicencio on 9 August 2023 and the increase in electoral violence throughout the region show that it is impossible to draw a clear-cut distinction between criminal and political violence. Although today’s political violence differs from previous civil wars which aimed at standing up to the national government, it serves political purposes such as maintaining the social, economic, and political status quo and controlling specific populations and territories.

Different actors are directly or indirectly involved in this violence, such as organised-crime figures or political, economic, and military elites, who directly or indirectly collaborate with non-state armed actors (NSAAs). It has a number of different manifestations, such as state repression, electoral violence, or gender-based abuse. The following maps show where in Latin America state and non-state armed actors are mainly fighting each other (Map 1) and where they are mainly targeting civilians (Map 2).

Map 1. Battles between State and Non-State Armed Actors in 2022

Source: Raleigh et al. (2010).

Map 2. Violence against Civilians in 2022

Source: Raleigh et al. (2010).

The maps show that violence varies considerably within and between Latin American countries. Violence against civilians is much more widespread than formal fighting between state and non-state armed actors. Other indicators of non-war forms also provide evidence for the high levels of violence in the region. According to the World Population Review (2023a, 2023b), the ten most violent cities globally are all located in Latin America (five in Mexico, three in Venezuela, and two in Brazil). The same source also states that the region has the highest crime indicators globally: seven of the top ten crime-afflicted countries worldwide are in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC): Venezuela, Honduras, Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana, El Salvador, Brazil, and Jamaica. Finally, Latin America is the most dangerous region worldwide for social activists and human rights defenders (Front Line Defenders 2023), and six of the eight countries around the globe where trade unionists were murdered are to be found in Latin America (ITUC 2023). These are undeniably political forms of violence, as they target key political and social actors advocating for reforms.

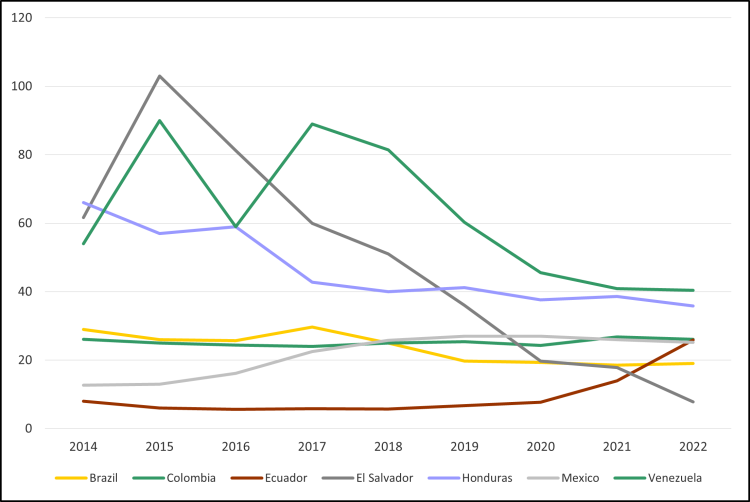

Although some of these states have long been among the world’s most violent countries, the phenomenon is not static: it varies with changes in global markets and the reconfiguration of power relations at the national and subnational levels. The recent increase in violence in Ecuador and the decreases in El Salvador and Venezuela are examples hereof. The high degree of flexibility and adaptability of NSAAs to these shifts is another important factor shaping levels of and spatial variations in violence.

Figure 1. Homicide Rates in Colombia, Ecuador, El Salvador, and Venezuela, 2014–2022

Source: InSight Crime (various years).

The increase in violence in Ecuador since 2020, for example, is the result of a combination of factors at different scales:

Global cocaine production and consumption increased significantly after a brief dip during the COVID-19 pandemic. Trafficking has adapted rapidly by changing transport modes and routes (UNODC 2023).

At the regional level, the Colombian peace agreement of 2016 and the subsequent demobilisation of the FARC (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia) guerrillas led to a process of reconfiguration and fragmentation among NSAAs there. While violence declined at the national level, it remains high in areas formerly dominated by the FARC – such as along the border with Ecuador – and over control of coca production and drug trafficking. The demobilisation of the FARC provided a window of opportunity for Colombian actors such as the Gulf Clan to move in, but also for foreign groups such as Mexican and European drug-trafficking organisations. In Ecuador, foreign drug organisations teamed up with local gangs to turn the country into a major regional trafficking hub.

This would not have been possible without some enabling developments in Ecuador. First, the latter’s Pacific coast and the port of Guayaquil became more important in the transiting of cocaine after the closure of the United States’ anti-drug base at Manta in 2009 by the government of Rafael Correa (2007–2017). In 2018, second, the Lenín Moreno government (2017–2021) dissolved the Ministry of Justice and the Technical Secretariat for a Comprehensive Drug Policy due to austerity measures. Both institutions played an important role in drug-prevention policies. Third, corruption is a serious problem in Ecuador, as evidenced by its ranking as 101st out of 180 countries in the Transparency International index. Fourth and finally, the political crisis during the presidency of Guillermo Lasso (2021–) and the lack of a coherent security policy have also been enabling factors. Faced with a lack of parliamentary majorities and the threat of impeachment, Lasso dissolved parliament in a process known as “muerte cruzada,” paving the way for new elections. Interestingly, the assassination of Villavicencio seems to have had no major effect on the election results. Congress remains fragmented and both candidates in October’s presidential run-off are emphasising a comprehensive rather than punitive security policy.

While the precise turn of events may be specific to Ecuador, the entanglement of domestic and global processes as well as of structural factors and actor dynamics can be seen throughout Latin America. They provide a breeding ground for violence and crime. This favours populist promises of “easy solutions” to what in reality is a much more complex problem.

History Bites Back: The Structural Context to Violence and Crime

What is rarely mentioned in media or government reports on crime and violence is how structural conditions show a similar entanglement of global, regional, national, and local developments. Take social inequality. International comparisons show that Latin America is the most unequal region worldwide (as measured by the Gini coefficient, for example). Democratisation and economic growth had improved both indicators by the time the first decade of the twenty-first century came around based on the resource bonanza, but a recent analysis summarises the overall trend as follows: “There have been improvements; they have not been enough; they have slowed” (Gasparini and Cruzes 2022). Perhaps even more serious from a violence perspective is the lack of prospects for social mobility (Houle 2019). In a study of 102 countries, 14 of the 19 LAC ones are in the bottom third in terms of social mobility – most of them at the very bottom of the scale. Last but not least, the region transmits intergenerational inequalities, which a recent study by the Andean Development Bank called Inherited Inequalities (CAF 2022).

For much of the twentieth century, inequality and marginalisation provided guerrilla groups and other NSAAs with a vast reservoir of young recruits made up of landless campesinos and urban slum dwellers. Globalisation and an extractivist development model have played their part in these continuities, as has the reduction of state finances due to the structural-adjustment programmes of the international financial institutions. Both processes have led to a loss of employment opportunities in the formal economy. As with the reduction of poverty and inequality, the growth of formal jobs slowed significantly before the pandemic while informal ones increased afterwards (Maurizio 2021).

Informalisation reduces social cohesion and promotes disintegration. Although many new forms of organisation and types of social movement have emerged in civil society, they tend to focus on selective or only local issues. Within one generation, patterns of social relations have changed significantly. Migration has been one of the individual responses to the various crises. The growth of evangelical churches, which emphasise individual rather than collective forms of action and coping, is another symptom. In terms of violence and crime, increasing social fragmentation has destroyed traditional patterns of inclusion and control.

A second element at the structural level relates to the capacity of state institutions to provide security and justice, which is often analysed in terms of the absence of the state. However, the problem is not so much an “absence” of state institutions, but rather their specific – often repressive – presence in areas where marginalised populations and minorities live, reproducing entrenched patterns of exclusion and power hierarchies (González 2017). Despite some far-reaching plans for security-sector reform in Latin America that came as part of democratisation and peacebuilding processes, the issue of violence has more often than not been used in public discourse to forestall substantial change in the security sector – such as limiting the use of the armed forces to securing national borders or making the judiciary independent of politics. Both of these reforms, however, are crucial to tackling transregional crime.

Third, despite the debate on “criminal” violence, ample evidence shows that economic, political, and social elites at the local and national level collaborate with organised crime. This makes them part of the problem rather than part of the solution. Money laundering, widespread corruption, and the co-optation of state institutions by violent actors are far more important than security discourses suggest. Colombia's “parapolitics” scandal is a case in point, as is the undermining – if not elimination – of judicial independence by corrupt majorities in Guatemala’s government and parliament. While in Colombia the judiciary was able, albeit very slowly, to at least partially address these problems, the apparently too successful International Commission against Impunity and Corruption in Guatemala was forced out when it targeted the illegal financing of electoral politics. These are just two high-profile examples of the collusion between politics and crime; there are many more that have gone unchallenged in the region.

Coping with Violence – Nayib Bukele versus Gustavo Petro

The experience of violence affects societies in different ways: In addition to the direct cost in terms of human lives and material damage, it is often constitutive of a society’s self-image and of its legitimation and acceptance of the phenomenon. Displacement, flight, and migration change the spatial and social composition of the population as well as access to and control over natural resources. In many cases, the destruction of social relations and the lack of civilian instruments for conflict transformation contribute to lowering the threshold for the use of violence in everyday life.

However, violence not only destroys societies but also “reorganises” them: Policies to manage or reduce its different manifestations are a case in point. In a climate of fear and of a lack of trust, often reinforced by “moral panics” and populist political discourses, repressive approaches are more likely to be accepted. This can lead to the creation or renewal of vertical relationships of loyalty behind formal democratic facades. However, the emergence of networks of mutual support, assistance, and solidarity among victims, refugees, and diasporas may offer alternative ways of coping with and reducing violence. As with many other complex phenomena, responses to violence and crime are rarely either/or ones but will include elements of both approaches.

Although the governments of Colombia and El Salvador currently appear to be at different ends of the political spectrum in terms of dealing with NSAAs, both societies have extensive experience with repressive and dialogue-based approaches alike.

Repression

In Colombia, after the failed peace process with the FARC in the late 1990s, then-President Álvaro Uribe (2002–2010) pursued a policy of heavy militarisation. The armed forces almost doubled in size, and the US-backed Plan Colombia provided training and equipment for counternarcotics operations. Violence declined significantly during Uribe’s first term in office. However, these developments were accompanied by gross human rights violations. According to the Comisión Colombiana de Juristas (2007), more than 11,000 people were killed or assassinated outside the armed conflict during Uribe’s first term. Paramilitary groups (tolerated or even supported by the state) were responsible for 61 per cent of the deaths, guerrilla groups for 25 per cent, and the state directly for 14 per cent thereof.

In Colombia, two problems with taking a repressive approach stand out during different time periods: First, the country’s geography (three mountain ranges and a lack of infrastructure) makes territorial control by the state difficult, even with the second-largest military in South America. Second, and probably more importantly, the armed forces and police have either turned a blind eye to or even collaborated with those NSAAs seeking to preserve the social, economic, and political status quo – namely, private armies and paramilitary forces. On the other hand, NSAA groups and their demobilised members who sought to change the prevailing order have been persecuted, as have many civilian political and social groups too (Aviles 2012). The assassination of more than 3,000 representatives, candidates, and members of the Unión Patriótica – a party founded by demobilised FARC members in the mid-1980s – is the most notorious example.

The relationship between repression and the state is even more evident in the case of El Salvador. Here, governments of different ideological persuasions have used “iron fist” policies to contain and reduce the violence of Central America’s most hardened street gangs – the Mara 18 and the Mara Salvatrucha. These strategies resemble military operations during the civil war (1980–1992) and have undermined the implementation of the profound security-sector reforms envisaged in the 1992 peace accords. Two elements stand out: first, the continued use of the armed forces for public security, when their role should have been limited to guaranteeing the integrity of the country’s borders; second, the discursive construction of insecurity as the main threat to the country, despite evidence that the maras are not responsible for the majority of violence (Kurtenbach and Reder 2021).

Repressive strategies to reduce violence in Latin America have a number of elements in common. First, in many contexts a state of emergency is declared (El Salvador: July 2022; Honduras: December 2022; Ecuador: August 2023). This not only increases the power of the armed forces and the police but also restricts basic human rights, such as the right of assembly or, as in El Salvador, due legal process. A second, often related element is the rise of a populist discourse that legitimises punitive responses and undermines democratic standards and human rights, especially for political opponents. President Bukele’s attacks on journalists and human rights defenders both inside and outside the country are illustrative. From this perspective, Ecuador is an interesting counterfactual because, to the surprise of many, in the presidential elections on 20 August the candidate with the most punitive approach to violence, Jan Tapic, only came fourth. Finally, beyond the direct and indirect costs of repression vis-à-vis democratic governance, the rule of law, and civil society, there is no evidence that these policies work beyond a mere short-term reduction in violence. To make matters worse, Latin American prisons are not only notorious for the inhumane conditions in which inmates are held but also for being the most efficient schools for crime and murder due to overcrowding and the strict hierarchies established under the gangs controlling them.

“Bargaining with the Devil …”

So what about dialogue to bring NSAAs under the rule of law, to demobilise them, and to disarm them? Violent countries all have some experience with this approach, which Vanda Felbab-Brown (2020) illustratively titled Bargaining with the Devil to Avoid Hell?. Since the end of the Cold War, peace agreements have ended civil wars: starting in El Salvador in 1992, followed by Guatemala in 1996, and most recently in Colombia between the state and the FARC in 2016. Even though the governments of the day had branded these NSAAs criminals and terrorists for most of the civil-war era, they eventually sat down and talked with them. These negotiations were largely supported by international actors such as the United Nations or the so-called Groups of Friends.

There have also been talks with NSAAs framed as “criminal” rather than “political” actors, but these tend to be much more complicated. First, labelling the groups in this way reduces the legitimacy of the dialogue process per se. While talks with NSAAs are often confidential (at least until an agenda is agreed), this creates distrust in overall proceedings – especially in contexts where the government is perceived to be a tacit ally of the NSAAs in question. The truce between El Salvador’s three main gangs in 2012–2014 is a case in point. Here, the government denied having any role in that outcome – even though it was present at least as a guarantor. After a year, growing opposition from various actors, such as the public prosecutor and the Catholic Bishops Conference, undermined and ended the process (van der Borgh and Savenije 2019). Violence increased to unprecedented levels. Similar developments can be observed in other contexts after failed talks and negotiations. Even in successful cases, violence rarely ends completely; more often than not, many combatants remain armed and form or join other NSAA groups.

However, the biggest dilemma facing those seeking dialogue is the need for a minimum level of justice and reparation for the victims, as well as adherence to international standards on the rule of law. Colombia shows this very clearly: At the end of his first presidency, Uribe initiated a process with the paramilitary groups that had united under the name “Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia” (United Self-Defence Forces of Colombia, AUC). Colombian civil society and many international actors were suspicious that this was aimed at legalising the AUC’s violently accumulated wealth (most of it in the form of land grabs coming after the forced displacement of previous owners).

Colombia signed the Rome Statute in 1998 and ratified it in 2002, but excluded the prosecution of war crimes for seven years. On this basis, and due to the fact that Uribe did not have a majority of his own in Congress, domestic and international actors lobbied for adherence to a minimum international standard of justice. Although this was still criticised by human rights organisations, it helped to demobilise around 25,000 paramilitaries and to justify the Special Justice Mechanism for the FARC ten years later.

Nevertheless, the Petro government’s (2022–) current policy of “total peace” provides a profound illustration of the difficulties of dialogue with a multiplicity of NSAAs with different agendas and degrees of social embeddedness. At the heart of the Colombian debate is the distinction between the “political” and “criminal” aims of the NSAA – as some protagonists’ biographies show, achieving this in a clear-cut manner is impossible. Dario Antonio Úsuga David (alias Otoniel) – leader of Colombia’s largest criminal organisation, the Gulf Clan – began his “career” as a guerrilla fighter, demobilised, joined the paramilitaries, demobilised again, and then became the head of the Gulf Clan.

Ecuador is another example of changing strategies and their impact on violence: In 2007, then-President Correa legalised some of the gangs and homicide rates dropped significantly. However, the austerity policies of his successor, Moreno, reduced funding for key state institutions such as the Technical Secretariat for a Comprehensive Drug Policy. Outgoing President Lasso militarised prisons and largely ignored the issue of rising violence. While politicians and administrations develop their policies according to (short) electoral cycles and often populist strategies, NSAAs can afford to take long-term approaches and have proven themselves very flexible in adapting to changing transregional and global contexts.

The Need for Long-Term and Consensus-Based Strategies

What this brief review of the structural drivers and some select experiences of coercive and negotiated violence reduction shows is that transforming NSAAs is ultimately a highly complex endeavour. Strategies need to focus not only on those who have the weapons. The dynamics of violence, the specific contexts it manifests in, and the entanglement of violent and non-violent processes also need due consideration.

The first challenge is whether or not to talk to members of NSAA groups, and then how to convince them to lay down their weapons. As a Colombian colleague noted, they may need to be given an offer they cannot refuse. But they also must take responsibility for the violence they have committed, especially against civilians. Transitional-justice processes and international experience with leniency programmes show that this is possible. The key requirement is that disarmament and demobilisation must be both transparent and independently monitored. The involvement of civil society herein is essential to build legitimacy and acceptance for these processes. Closely linked to these points is the need to protect civil society actors (e.g. activists, pro-democracy and inclusivity agents, human rights defenders), as they are key to monitoring and advocating for strategies based on the rule of law, human rights, transparency, and accountability.

Second, the dynamics of violence are also fed by developments beyond specific local or national territories. Strategies that do not address these dynamics will at best shift violence to other places or across borders, as we have seen in Ecuador. The reconfiguration of power relations also affects these dynamics. Colombia is just one example where we can see that violence is increasingly affecting political and social actors such as human rights activists, representatives of social and ethnic minorities, and demobilised ex-combatants. This shift can lead to both old and new cycles of revenge and violence.

Third, specific contexts need to be taken into account. This is obvious in the case of violence employed to control areas home to legal and illegal profitable resources (gold, coca, and similar). Here, the state may be only one of many actors; also, not all NSAAs have national objectives but may rather have local agendas (and influence). On the other hand, local and subnational developments can have an impact at the national level too. In border regions, such as between Colombia and Venezuela, NSAAs may find a safe haven and illegal goods can easily cross state lines. Regional strategies are therefore important to prevent balloon effects: namely, the shifting of production and trafficking from one side of the border to the other as pressure increases. A common feature of violent local contexts is a lack of social infrastructure and civilian livelihoods. Here, NSAAs often play an important role in competing with or substituting for the lack of governance and provision of public goods by national and local authorities.

After all, violent and non-violent developments are closely linked, as the restrictions on basic human rights within punitive and coercive strategies show. At the same time, security policies must also include NSAAs who finance or incite violence for their own political, social, or economic reasons. These networks must be identified and dismantled, and the actors involved brought to justice.

Comprehensive and long-term policies are needed to address the historical and structural violence witnessed in Latin America. These must include the de-legitimisation of the use of violence and public policies to reduce social inequalities. Violence prevention must also focus on reducing impunity, reforming the security sector, and prioritising the rule of law and human rights. Democracy means governing for a limited period of time, so historic tasks – such as those outlined here – cannot be solved in one legislative term alone. It is therefore necessary to build a broad consensus in society supporting these strategies to reduce violence based on the rule of law.

Footnotes

References

Borgh, Chris van der, and Wim Savenije (2019), The Politics of Violence Reduction: Making and Unmaking the Salvadorean Gang Truce, in: Journal of Latin American Studies, 51, 4, 905–928.

CAF (2022), Inherited Inequalities. The Role of Skills, Employment, and Wealth in the Opportunities of New Generations, Report on Economic Development, accessed 31 August 2023.

Comisión Colombiana de Juristas (2007), Colombia 2002-2006: situación de derechos humanos y derecho humanitario, Bogotá, accessed 31 August 2023.

Felbab-Brown, Vanda (2020), Bargaining with the Devil to Avoid Hell?, Barcelona: Institute for Integrated Transitions, July, accessed 31 August 2023.

Front Line Defenders (2023), Global Analysis 2022, Dublin, Brussels, accessed 31 August 2023.

Gasparini, Leonardo, and Guillermo Cruces (2022), The Changing Picture of Inequality in Latin America: Evidence for Three Decades, 9 August, accessed 17 August 2023.

González, Yanilda María (2017), “What Citizens Can See of the State”: Police and the Construction of Democratic Citizenship in Latin America, in: Theoretical Criminology, 21, 4, 494–511.

Houle, Christian (2019), Social Mobility and Political Instability, in: Journal of Conflict Resolution, 63, 1, 85–111.

InSight Crime, Annual Homicide Roundups 2014-2022, accessed 31 August 2023.

ITUC (2023), Global Rights Index 2023, Brussels: International Trade Union Confederation, accessed 31 August 2023.

Kurtenbach, Sabine, and Désirée Reder (2021), El Salvador: Old Habits Die Hard, in: David Kuehn and Yagil Levy (eds.), Mobilizing Force: Linking Security Threats, Militarization, and Civilian Control, Boulder, Col: Lynne Rienner Publisher, 117–138.

Maurizio, Roxana (2021), Employment and Informality in Latin America and the Caribbean: An Insufficient and Unequal Recovery, Technical Note, September, Geneva: ILO, accessed 31 August 2023.

Raleigh, Clionadh, Andrew Linke, HåvardHegre, and Joakim Karlsen (2010), Introducing ACLED-Armed Conflict Location and Event Data, in: Journal of Peace Research, 47, 5, 651–660, accessed 31 August 2023.

UNODC (2023), Global Report on Cocaine 2023. Local Dynamics, Global Challenges, March, Vienna: UNODC, accessed 31 August 2023.

World Population Review (2023a), Most Violent Cities in the World 2023, accessed 17 August 2023.

World Population Review (2023b), Crime Rate by Country 2023, accessed 17 August 2023.

Acknowledgement

Thanks to Carla Kienel for providing the data visualisation and maps.

Editor GIGA Focus Latin America

Editorial Department GIGA Focus Latin America

Regional Institutes

Research Programmes

How to cite this article

Kurtenbach, Sabine (2023), Latin America’s Search for Security: Between Repression and Dialogue, GIGA Focus Latin America, 3, Hamburg: German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), https://doi.org/10.57671/gfla-23032

Imprint

The GIGA Focus is an Open Access publication and can be read on the Internet and downloaded free of charge at www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publications/giga-focus. According to the conditions of the Creative-Commons license Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0, this publication may be freely duplicated, circulated, and made accessible to the public. The particular conditions include the correct indication of the initial publication as GIGA Focus and no changes in or abbreviation of texts.

The German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) – Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien in Hamburg publishes the Focus series on Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and global issues. The GIGA Focus is edited and published by the GIGA. The views and opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the institute. Authors alone are responsible for the content of their articles. GIGA and the authors cannot be held liable for any errors and omissions, or for any consequences arising from the use of the information provided.