- Home

- Publications

- GIGA Focus

- Iran’s Uprisings: A Feminist Foreign Policy Approach

GIGA Focus Middle East

Iran’s Uprisings: A Feminist Foreign Policy Approach

Number 6 | 2022 | ISSN: 1862-3611

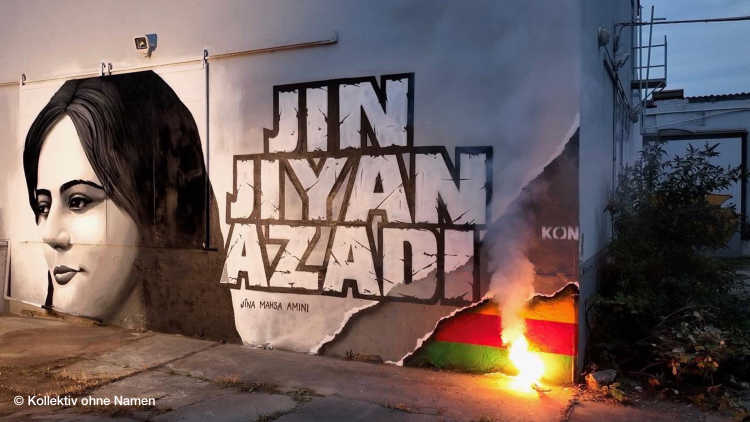

The current uprisings in Iran following the death in police custody of Mahsa Jhina Amini, a young Kurdish woman, carry strong implications for states that have adopted a “feminist foreign policy” (FFP). The ongoing protests there allow such states as Germany to showcase the potential of their FFP by responding to the violation of women’s and other marginalised groups’ rights happening right now.

The intersectional and inclusive viewpoint within the feminist scholarship must be indivisible from feminist foreign policy-making. Those states who have adopted an FFP must establish clear-cut and practical measures to distinguish it from current foreign policy approaches.

Iranian women are at the epicentre of the current uprisings in Iran. However, the protests are intersectional and have mobilised a wide spectrum of marginalised groups. An FFP should showcase the voices of the latter and propose sound measures to defend their rights. In this vein, the political agency and demands of women and other marginalised groups in Iran must be clearly acknowledged and prioritised.

The standpoint of Iranians and women should be inseparable from all measures taken against the Islamic Republic of Iran. Therefore, modes of engagement with the latter should not be restricted to the country’s nuclear programme if “security” is conceived of from a feminist viewpoint. Any compromise over the nuclear negotiations with Iran that has as its trade-off the continuation of human rights’ violations shall not be made under a sound FFP.

Policy Implications

Alternative measures should be taken in response to the brutal crackdown on the Iranian people by their government. Intersectional media outreach, sanctions targeting the political establishment, forming a diverse advisory team, and including gender in the collection as well as analysis of information are among such desirable measures. Supporting Iranian protesters and feminist networks on the ground and incorporating their standpoint should be the primary mode of engagement used.

Uprisings in Iran and German Feminist Foreign Policy Coinciding

The death of Mahsa Jhina Amini, a 22-year-old Kurdish woman, at the hands of the so-called morality police flooded cities across Iran with anger and sparked a new wave of nationwide uprisings, following mass protests in 2017 and 2019 too. The demonstrations initially set off with protesters chanting against the mandatory veiling of women that the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) has penalised since 1979 under its Sharia law-inspired criminal codes. Soon after the uprisings began, however, abolishing the compulsory hijab became intertwined with other sociopolitical demands – ones already articulated in the 2017 and 2019 demonstrations – directed against the entirety of the Islamic Republic’s political establishment.

In light of this, activists, policy analysts, and academics have voiced their criticism – particularly on social media – of the international community for remaining silent. In fact, Amini died in the same week that the German Federal Foreign Office (FFO) held its first summit on “feminist foreign policy” (FFP). Many considered the FFO’s response to the protests and human rights violations in Iran to be insufficient and to not adhere to the high standards of an actual FFP.

It is still very difficult for political analysts as well as ordinary citizens to comprehend what the implications of an FFP are. Many critics tend to believe that it is just a policy for women. However, an FFP goes beyond that, as it does not just play out in times of war and violent conflict but is a cross-cutting issue that has real-life implications for citizens’ daily lives. The protests in Iran that started off with the rejection of the compulsory hijab and broadened into country-wide protests against the authoritarian rule of the Islamic Republic are a good case in point to illustrate this – and, indeed, also what a German response in line with a genuine FFP could and should have looked like.

A New Era in German Foreign Policy-Making: A Feminist Foreign Policy

When the German government published its coalition agreement (“Koalitionsvertrag”) in December 2021, they introduced a novel aspect to the country’s foreign policy. According to the agreement:

Together with our partners, we aim to strengthen the rights, resources and representation of women and girls worldwide and promote social diversity in the spirit of a feminist foreign policy. (SPD, Grüne, and FDP 2021: 114)

At that time, however, not too many were sure what exactly was meant by this. Would it mean that from now on the needs of women would be prioritised in foreign policy-making? Or, that mostly women would be hired at the FFO? Was the new foreign minister Annalena Baerbock just anti-men in general? In fact, the astonishment and confusion over this chosen phrasing is understandable, as not many states have adopted an FFP so far. And those that have done so embrace different approaches to and understandings of what even constitutes an FFP in the first place.

A Few Takeaways from Feminist International Relations Theory

The construction of global politics has long been argued to be male-dominated in its conception and inclusion of experiences (Enloe 1989; Tickner 1992). The voices of women – and of other marginalised identities – have either been completely omitted or not equally accepted. Feminist theory in International Relations (IR) first emerged to change the masculine theorisation of concepts in the discipline, doing so by now including gender and the experiences of women in particular. As J. Ann Tickner, a feminist IR scholar, famously put it: “Politics and masculinity have a long and close association” (Tickner 1992: 6). To deconstruct this association, feminist IR literature offers two crucial elements: The first is the incorporation of the voices of the oppressed in theorisation and giving marginalised subjects the opportunity to frame their oppression themselves – that is, from their own standpoint (for two different accounts of the intersection of standpoint theory with IR, see: Keohane 1989; Tickner 1992). The second, meanwhile, is a refashioning of the concept of “security” and how it should be best understood by policymakers (for some contributions hereto, see: Sjoberg 2010). A revised notion of security apposite to a genuine FFP can only emerge once it is both understood as being threatened by unequal gender relations and its intersection with other categories of oppression acknowledged.

To further add to this caveat, according to Adebahr and Mittelhammer (2020) there are three key elements to an FFP:

Expanding the definition of security: A feminist understanding of security differs from traditional views that merely understand the phenomenon as the end of violence and war. Acquiring security cannot be reduced to military gains and armament policies but needs to be widened to human security – including economic, health, and environmental security, as well as social justice. "Violence is not seen as an isolated phenomenon but as a symptom of 'structural violence.' This means that systemic inequalities and unequal distribution of power and resources can be the root causes of violence. To turn violent conflict into sustainable peace, these causes need to be addressed" (Adebahr and Mittelhammer 2020: 8).

Decoding power relations: Decoding power relations lies at the core of an FFP. It is important to understand who holds power and what the motives behind their unwillingness to share it are. For this purpose, an intersectional understanding is indispensable: namely, how the intersection and interplay of different forms of inequalities, such as racism, classism, and sexism, create new dimensions of inequality and can further deepen power divides. Thus, if the solution is just to add more (white) women to the realms of foreign policy-making, such power imbalances will remain. Including more diverse voices is, therefore, essential (Narlikar 2022).

Recognising women’s and marginalised groups’ political agency: Women should be “recognized as multifaceted security providers rather than merely as victims in need of protection” (Adebahr and Mittelhammer 2020: 8). We need to identify barriers to the participation of women in politics and indeed all spheres of power. This goes beyond merely ensuring that women have a seat at the table: for women to become genuine political agents, equal resources and information need to be provided to them. Otherwise, their participation will only have modest effects on political decision-making. What has been said about women needs to be extended to all marginalised groups. In the case of Iran, for instance, a Kurdish woman faces more acute and distinct obstacles than a Persian woman does. She is not just excluded because of being a woman but also due to her Kurdish identity. Her needs must, therefore, be addressed differently. An intersectional perspective is consequently indispensable to the realisation of political agency for women and marginalised groups alike.

Any self-claimed FFP needs to be informed by the above reconceptualisations of how global politics works – and must work. This can only happen by granting special attention to the voices of the oppressed and incorporating them at different levels of security frameworks – national, regional, and global.

The Emergence of a German FFP

Even though the new Swedish government recently announced the removal of the term “feminist” from its foreign policy, in 2014 it was still the first country in the world to announce an FFP. While, since then, a few others have followed suit (Canada in 2017, France in 2018, Mexico in 2020, Spain and Luxembourg in 2021), Sweden’s policy remains the most comprehensive to date (for a comparison of these different approaches, see for instance: Oas 2019; Thomson 2020; Zhukova, Rosén Sundström, and Elgström 2022). The FFO also alludes to the Swedish model and pledges to incorporate the “3R+D” approach: the promotion of the rights, representation, and resources of women and marginalised groups, as well as diversity.

Figure 1. Feminist Foreign Policy: A Timeline

Source: Authors’ own compilation.

While Germany so far has not presented its envisaged FFP in writing, it appears that its approach thereto is more far-reaching than Sweden’s. One of the main criticisms of the latter’s framework is its binary conceptualisation of gender and its focus on women and girls. Hence, Sweden neglects the rights of, for instance, the LGBTQ+ community and other marginalised groups (Thomson and Clement 2019). By not defining a feminist policy as one that only addresses gender equality, Germany, on the other hand, broadens the scope here and ensures that an FFP is not just a policy for women but for all marginalised identities. When asked in March 2021 whether from now on only women were allowed to speak at the FFO, Baerbock replied:

No, it is exactly the opposite: a FFP is not about excluding, but about including. It’s not about hearing fewer voices, but more voices. It’s about hearing all the voices of society. And: a feminist foreign policy is not a “women’s issue.” Because we all benefit from it! (Auswärtiges Amt 2022)

Further, Germany understands its FFP as intersectional – meaning that it takes into account the intertwining of and interactions between different forms of social disadvantage.

What becomes evident, thus, is that even though Germany has announced its intention to implement an FFP, it should not merely be a policy for women but rather human-centred per se. A policy that puts the people who governments and those in power should serve at the centre of decision-making processes. While it is often unclear what this should look like exactly, the current uprisings in Iran represent a good example with which to discuss these aspects more concretely.

The Changing Dynamics of the Uprisings in Iran: “Women, Life, Freedom”

Women are at the forefront of the current Iran protests, especially as compared to previous mass demonstrations in 2017 and 2019. It is crucial to avoid the fallacy of reducing the cause of the current demonstrations to solely feminist demands and the abolition of the compulsory hijab. In this sense, the current wave of protests are profoundly intersectional – mobilising a vast spectrum of marginalised identities. There is, however, a central and evolving feminist symbolism within the protest dynamics that has mobilised oppositional groups in an unprecedented manner. Iranian women are reclaiming their bodies and demanding their alternative and full participation in the public sphere. They have employed uniquely feminist symbols – as embodied in subversive, performative acts such as cutting their hair, twirling their headscarves in the air, and burning the latter in public spaces – to demand substantial political changes aimed ultimately at toppling the clerical regime.

For the first time, protesters are chanting slogans – “Women, Life, Freedom”; “Freedom, liberty, down with the compulsory hijab”; “No to the scarf, no to repression, [we want] freedom and equality”; “Our scarf is the rope [by which] we will hang you!”; “We are all Mahsa! We will fight against you [the regime]” – to express their utmost rage against the state’s misogyny. The embodiment of the mentioned slogans is unprecedented in the history of Iranian protests over the last decade. The Islamic Republic seems to be aware of this changing dynamic. On 21 September, the head of the Special Units Command of Faraja – one of the main police arms of the state’s machinery of repression – announced that, for the first time, they had formed a “female anti-riot unit” – specifically to “control the female protesters” (MehrNews 2022). This shows that the state has acknowledged the preponderance of females among the protesters and, at the same time, is signalling its intended stronger and “more effective” repression of them.

These protest symbols have already reached beyond Iran’s borders, with at the regional level women in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria having publicly shown their solidarity with their Iranian counterparts – while also contesting their own governments by imitating the protesters’ performative acts. The Iranian diaspora, with the support of non-Iranians, have raged against the IRI – notably in Europe, the United States, and Canada – by replicating the subversive feminist symbols of the movement in public spaces. The level of international solidarity shown with the Iranian protesters has also been unprecedented. From women’s rights activists to celebrities and politicians across the world, the death of Mahsa Jhina Amini and subsequent rage of Iranians against the Islamic Republic have created a historical momentum for the decade-long protests in the country.

Internationally, the European states – especially the ones who claim to have made a feminist agenda among their top foreign policy priorities – have remained ambiguous in their responses. The standpoint of women, as well as of other parts of Iranian society, has not yet been recognised and understood correctly – mainly due to these states’ negligence of women’s movements both in Iran and in the Middle East more broadly. Women in Iran, along with other social factions, are demanding fundamental and structural political change explicitly targeted at unseating the Islamic Republic – and the Supreme Leader at its helm.

Changing the political establishment is taking precedence in the course of women attributing the source of their oppression to state ideology, which has proved to be irreconcilable with the former’s standpoint. Such oppression is rooted in institutionalised patriarchal gender relations where imposing the hijab is one among many state techniques of control over women’s bodies and participation in the public sphere. Unequal access to the labour market, inadequate protection by the law in cases of gender-based violence, and the criminalisation of abortion and sexuality – particularly outside the institution of family – are all indicators of how the IRI has cemented these patriarchal contours.

The Islamic Republic defines the role of its established state as being morally responsible so as to guide society per its radical interpretation of Sharia law. Waiving the compulsory hijab and allowing women’s participation in the public sphere are things that government authorities and the clergy have been unwilling to compromise on – especially as they are deeply tied to the IRI’s core identity as a state. From the Supreme Leader himself, to Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps officials, to Friday prayer imams and different government employees, all these camps have repeatedly insinuated that the hijab cannot be compromised on so long as the Islamic Republic continues to exist. On 30 September, amid growing protests, several Friday prayer imams across the country reiterated the official narrative around the hijab and blessed the police for cracking down on the demonstrations (ISNA 2022). Within this context, after years of experiencing state repression, now the only imaginable solution from the standpoint of the women’s movement in Iran – if its cause is to be victorious – is to undergo an entire change of political system – thus sidelining completely any notion of a “reformist agenda.”

Europeans’ Foreign Policy towards Iran: The Precedence of the Nuclear Programme

Over the past two decades, and at least since the leaking of Iran being engaged in clandestine nuclear activities, the West has predominantly engaged with the country on the grounds of seeking to contain its nuclear programme. The IRI’s related progress – particularly in terms of acquiring a nuclear bomb – has been perceived by the West as the main security threat posed by the Middle Eastern state. This has resulted in a series of international sanctions – United Nations Security Council Resolutions, 1737, 1747, 1803, and 1929 – that have targeted different layers of the Iranian economy in order to internationally isolate the country. This dominant focus on preventing Iran from acquiring nuclear weapons would lead to the conclusion of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) in 2015. Off the table ever since the US withdrew in 2018, the various parties are now negotiating a new such deal – yet without revamping the previous setting, agenda, and structure of the processes related to that.

On the one hand, the negotiations are still very exclusive, as other Middle Eastern countries have not been included in the process. On the other, dialogue and diplomacy with the Islamic Republic over its gross human rights violations and proposed countermeasures have been relatively limited – both in scale and intended outcomes. The European Union first introduced sanctions in 2011 against a number of individuals and institutions in Iran who were involved in the repression of “the Green Movement.” In 2019, after another brutal state crackdown on protesters, the EU introduced a somewhat similar set of restrictive measures to sanction those involved in violating human rights. The enacted punishments have carried a rather symbolic meaning without offering tangible outcomes, mainly due to the compromises Europeans had to make so as to maintain talks with Iran over its nuclear programme. In the context of the current Iranian uprisings, European states have not proposed a proportionate response that could nurture the core ambitions of the protesters. In particular, what is noticeably lacking is the use of inclusive language and concrete measures – two crucial aspects of a sound FFP. The EU did recently declare a new set of sanctions to be implemented against the IRI and, in a short statement, condemned “the disproportionate use of force” by Iran’s security forces against the protestors on behalf of the Bloc’s member states. But none of this goes far enough. While the statement dismissed the demands of not only women but Iranian protesters in general, it remained vague about the potential measures that the EU envisions turning to in response – except the introduction of yet more sanctions. Additionally, the statement lacks a gender-sensitive and inclusive-intersectional communication strategy with regards to the acknowledgment of the different axes of oppression encapsulated by the Iranian protests.

What an FFP Should Look Like: From Theory to Practice

Feminist IR criticises, as noted, the male-focused conception of global politics that is “associated with masculinity” (Tickner 1988: 433). Two facets vital to any sound FFP have not been part of the nuclear negotiations: namely, a new definition of security that includes social security and a reassessment of how certain countries perpetuate power imbalances respectively. The limited initiatives taken against Iran’s human rights violations in the past, compared to in the face of its nuclear programme, reveal a rather restricted and narrow understanding of security. Containing a nuclear Iran has been conceived of as the main foreign policy priority due to a latent notion of the precedence of “hard” security, something exclusively drawn on in the framing of national security. Fundamental concepts such as the anarchic nature of the global order, benefit maximisation, and deterrence have, in consequence, informed the core of states’ national security strategies.

A genuine FFP must, however, challenge and reframe the latter conception while, simultaneously, being aware of the limits of such a stance. Under an FFP, it is equally important to weigh up normative notions of security in the overall national security framework and corresponding interactions with other states. Supporting minority and human rights, gender equality, and self-determination should, then, converge with hard security goals. Balancing such a synthesis is challenging – and perhaps the main constraint to adopting an FFP – when the predominant “valid” form of interaction between states is seen as being so as exclusively based on “realist” understandings.

The measures taken against human rights violations in Iran, in addition to the other largely rhetorical responses of EU member states, therefore lack two central elements – that with crucial policy implications. First, gender-sensitive and intersectional language has not been incorporated into the core message sent by these measures – hence also affecting their signalled implications. These measures have been unable to understand, or at least address, the roots of oppression and therefore advocate suitable corresponding counteractions. Second, putting sanctions in place as a form of punishment has always been deemed the most effective tool to counter human rights violations and hold those responsible accountable. While there is strong evidence that sanctions rarely lead to foreign policy changes, such measures at the very least have a symbolic dimension and normative power to them. Whether one either supports or denies the effectiveness of sanctions, the use of them is not the only viable option to hand – especially within the framework of an FFP. If pursued, however, they should target those in power and not the entire population.

Lastly, within the context of the ongoing nuclear negotiations it is of key importance that the European side do not accept the repression of Iranians as a trade-off to containing the IRI’s threatening nuclear behaviour. If any form of interaction, like the JCPOA, is to be sustained with the regime, strict preconditions must be established to ensure adherence to human rights obligations and to corroborate what the Iranian people are now demanding. Germany must take the lead on the latter to make manifest its normative FFP. The current Iranian uprisings are an opportunity – and could be a starting point for the European states, Germany in particular with its recent adoption of an FFP – to formulate a more comprehensive account of security and develop particular measures in line with a feminist agenda through a proper and inclusive response to the intersectional human rights violations taking place.

Elements of Germany’s Possible FFP Towards Iran

Germany so far has been the foremost critic of the IRI’s handling of the recent protests. Foreign Minister Baerbock has condemned the Iranian regime for its brutal crackdown, and indeed continues to do so. Germany has a rather positive reputation among Iranians, and could use this opportunity to cement its leadership role in the EU and shape the latter normatively. It needs to be stressed that no single measure is sufficient. An FFP will not be achieved by solely enforcing gender quotas – either at the FFO in particular or within state institutions more broadly. The FFO should be a pioneer in advocating for the rights of women and marginalised groups by, first, ensuring a diverse workforce and inclusive work culture within its institutional walls. Further, a novel and broader understanding of security needs to be established that could decouple the concept from conventional notions of “realpolitik.” Next to these structural and institutional changes, other practical measures can be taken in the meantime. The case of Iran illustrates this ideally.

Comprehensive and intersectional media outreach: The FFO could start more forcefully using its social media platforms to voice its support for protesters in Iran, specifically via an intersectional lens. By only focusing on women and leaving other affected communities behind, a sound FFP cannot ever be achieved. Iran is a multiethnic country where the rights of many minorities are curtailed. Not addressing the brutal crackdown on protestors in the Kurdish territories or in Zahedan, the capital of Sistan and Baluchestan Province, while condemning the attacks at the University of Sharif in Tehran, for instance, only adds to the discrimination Iran’s ethnic minorities face on a daily basis.

A new approach to security: Germany needs to listen carefully to and follow the demands of the Iranian people. These do not revolve around their country’s activities in the wider region or its nuclear programme. With women and other minorities leading this movement, they are asking first and foremost for basic human rights and a dignified life. In order to support them, more funding should be allocated to networks of human rights/women’s rights activists. While it seems rather difficult to directly engage with local networks in Iran, organisations outside the country – in addition to the diaspora in neighbouring ones – could help channel aid. Supporting people on the ground should always be a priority.

Recognising women’s and marginalised groups’ political agency: The FFO should consult with experts (drawn from these groups) on the ground in order to understand their needs better and implement appropriate strategies. Further, just as Germany has founded UNIDAS – a network bringing together women from Germany, Latin America, and the Caribbean – it could also work with experts in the Middle East to bring together women from different regional countries, including Iran. Moreover, the FFO could create special scholarships for women and marginalised groups in the Middle East in politics, journalism, technology, science, and business. This would facilitate mutual partnerships on cross-cutting issues as well as build an interregional feminist multidisciplinary network to create further knowledge exchange and transfer. Such a network could also help nurture a collective spirit as well as enhance solidarity.

Building a diverse advisory team on the Iranian uprisings: The FFO would benefit from establishing an interdisciplinary and diverse advisory team in order to receive scholarly advice on developments on the ground and to propose apposite real-time responses. It is important for such a platform to incorporate diverse voices from among Iranian and non-Iranian scholars and experts so as to avoid biased decision-making.

Including gender in information collection and analysis: Without accurate and reliable data we cannot satisfactorily report on human rights abuses in Iran. Reports by embassies or intelligence services should include information on gender as well as religious and ethnic issues. Doing so would help to both identify the sources of oppression as well as highlight their intersectional nature.

Footnotes

References

Adebahr, Cornelius, and Barbara Mittelhammer (2020), A Feminist Foreign Policy to Deal with Iran? Assessing the EU’s Options, Carnegie Europe, 23 November, accessed 7 November 2022.

Auswärtiges Amt (2022), Including Instead of Excluding: What is Feminist Foreign Policy?, 3 May, accessed 3 November 2022.

Enloe, Cynthia (1989), Bananas, Beaches and Bases: Making Feminist Sense of International Politics, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

ISNA (Iranian Students’ News Agency) (2022), Khatib-e Namaz Jom’e Tehran: Hesab-e Javanan-e Farib Khorde az Ashoub-garan Jodast (Tehran’s Friday Imam: We Should Distinguish the Deceived Young People from the Rioters), accessed 17 October 2022.

Keohane, Robert O. (1989), International Relations Theory: Contributions of a Feminist Standpoint, in: Millennium: Journal of International Studies, 18, 2, 245–253.

Mehrnews (2022), Nokhostin Mamooriat-e Yegan-e Zanan (The First Mission of Female Police Taskforce), accessed 17 October 2022.

Narlikar, Amrita (2022), German Feminist Foreign Policy: An Inside-Outside Perspective, Observer Research Foundation, 12 September, accessed 17 October 2022.

Oas, Rebecca (2019), What is Feminist Foreign Policy?, in: Definitions, 14.

Sjoberg, Laura (2010), Gender and International Security. Feminist Perspectives, New York: Routledge.

SPD, Die Grünen, and FDP (2021), Mehr Fortschritt wagen: Bündnis für Freiheit, Gerechtigkeit und Nachhaltigkeit, Koalitionsvertrag 2021, accessed 2 November 2022.

Thomson, Jennifer (2020), What’s Feminist about Feminist Foreign Policy? Sweden’s and Canada’s Foreign Policy Agendas, in: International Studies Perspectives, 21, 4, 424–437.

Thomson, Lyric, and Rachel Clement (2019), Defining Feminist Foreign Policy, Washington: International Center for Research on Women.

Tickner, J. Ann (1992), Gender in International Relations, New York: Columbia University Press.

Tickner, J. Ann (1988), Hans Morgenthau’s Principles of Political Realism: A Feminist Reformulation, in: Millennium: Journal of International Studies, 17, 3: 429–440.

Zhukova, Ekatherina, Malena Rosén Sundström, and Ole Elgström (2022), Feminist Foreign Policies (FFPs) as Strategic Narratives: Norm Translation in Sweden, Canada, France, and Mexico, in: Review of International Studies, 48, 1: 195–216, accessed 7 November 2022.

General Editor GIGA Focus

Editor GIGA Focus Middle East

Editorial Department GIGA Focus Middle East

Regional Institutes

Research Programmes

How to cite this article

Mirzaei, Diba, and Hamid Talebian (2022), Iran’s Uprisings: A Feminist Foreign Policy Approach, GIGA Focus Middle East, 6, Hamburg: German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), https://doi.org/10.57671/gfme-22062

Imprint

The GIGA Focus is an Open Access publication and can be read on the Internet and downloaded free of charge at www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publications/giga-focus. According to the conditions of the Creative-Commons license Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0, this publication may be freely duplicated, circulated, and made accessible to the public. The particular conditions include the correct indication of the initial publication as GIGA Focus and no changes in or abbreviation of texts.

The German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) – Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien in Hamburg publishes the Focus series on Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and global issues. The GIGA Focus is edited and published by the GIGA. The views and opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the institute. Authors alone are responsible for the content of their articles. GIGA and the authors cannot be held liable for any errors and omissions, or for any consequences arising from the use of the information provided.