- Home

- Publications

- GIGA Focus

- Bolstering the Bromances: Turkey’s and Iran’s Tightening Ties with Africa

GIGA Focus Global

Bolstering the Bromances: Turkey’s and Iran’s Tightening Ties with Africa

Number 6 | 2022 | ISSN: 1862-3581

Changing global dynamics resulting from the Russian invasion of Ukraine are creating opportunities for non-traditional actors – such as Iran and Turkey – to scale up their engagement with Africa. The African continent is particularly affected by the war: the blockage of grain export routes, the repercussions of Western-imposed sanctions, and globally surging prices have fuelled anti-Western discourses on the continent.

The consequences of the war against Ukraine have exacerbated the already existing challenges in Africa regarding food security, especially since the continent is heavily dependent on wheat imports from Russia and Ukraine. The war’s precedence over other crises in terms of immediate response puts already vulnerable regions at risk of greater food scarcity, humanitarian emergencies, and political instability.

Over the past twenty years, Turkey has emerged as a major humanitarian actor in Africa, promoting rhetoric that brands the country a benevolent brother of African states. Ankara’s role in brokering the grain shipment agreement between Ukraine and Russia has strengthened this narrative, with Turkey gaining recognition for having prevented more severe food crises.

In terms of Iran, Africa has played a crucial role in its international status-seeking agenda and intermittently as an economic survival sphere at times of deteriorating Iranian relations with the West. The developments regarding the domestic mass uprisings and unpromising nuclear negotiations – coupled with recent comprehensive cooperation with Russia since the beginning of the war – have led to a revitalisation of Iran’s engagement with African states.

Both Iran and Turkey deploy an amicable rhetoric, drawing on their discursive advantages – such as their Muslim identity and non-colonial history – to better engage with African states. In this way, they are able to leverage rising anti-Western sentiments among African leaders and societies to serve their foreign policy agendas.

Policy Implications

If European governments wish to remain relevant partners to African states and contain the anti-Western power projection of states such as Iran and Turkey, they should not depart from their commitments to the continent. They should exhibit a genuine commitment to horizontal partnerships and take a coherent approach towards authoritarian states to promote a value-based foreign policy.

The Russian Invasion of Ukraine: Changing Dynamics within the African Continent

The Russian war against Ukraine has sparked severe consequences globally. One of the regions particularly affected is the African continent, which is already battling the effects of climate change and the economic repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic. Against this backdrop, the Russian invasion of Ukraine is amplifying existing challenges. The blockage of grain export routes from Ukraine and Russia has hit the African continent particularly hard, as the latter is heavily dependent on these wheat imports, which comprise 44 per cent of overall wheat imports to Africa (UNCTAD 2022). Food insecurity and globally surging prices in pandemic-hit economies increase the risk of further humanitarian emergencies (e.g. in the Sahel and the drought-affected Horn of Africa). These challenges are viewed by parts of African societies as connected to Western-led sanctions against Russia and have thus fuelled anti-Western discourses.

The economic consequences are not the only elements of the war eliciting responses among the African public and political leaders. The war’s precedence over other conflicts and crises has led to concerns that other, particularly African, issues might be neglected. This perceived disproportionate attention to the war against Ukraine, as well as the unequal treatment of nationals from African countries fleeing Ukraine into the European Union, has been fiercely criticised as the application of double standards. Moreover, considering African states’ concerns about being caught up in an exogenous power competition, and for the sake of protecting their own needs and interests, many states have been reluctant to take (strong) stances vis-à-vis the conflict.

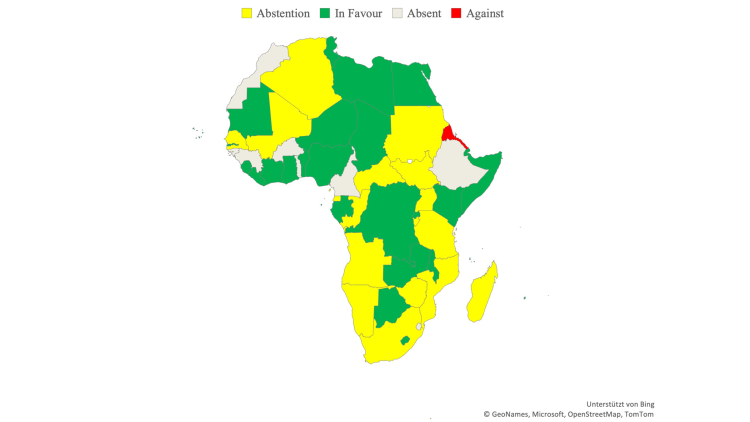

Against this backdrop, the European expectation that African states would follow suit with the Western sanctions against Russia failed to come to pass. This became particularly evident in African states’ voting behaviour in the United Nations General Assembly. While a significant majority of UN member states voted in favour of a resolution condemning Russia’s aggression against Ukraine in the early days of the war, nearly half of the 54 African member states did not support the resolution.

What these developments signal is twofold: On the one hand, they are indicative of Russia’s influence on the continent. Russia has long utilised advanced information tactics to spread disinformation within the African public sphere in order to buy support and construct hyper-imaginaries of historical ties between Russians and former liberation movements in Africa. Russia’s rising influence is illustrated in material terms by the expansion of Russian mercenary networks, particularly in the Sahel. Moreover, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), Russia was the largest arms exporter to Africa between 2017 and 2021 (Wezeman, Kuimova, and Wezeman 2022).

On the other hand, African countries’ rejection of Western positioning, despite their reliance on Western aid, shows their eagerness to navigate multiple partnerships and leverage the diversification of external partners for more strategic autonomy. While this appears to negatively affect or at least not benefit European or American relations with their African counterparts, it creates new opportunities for emerging non-traditional actors on the continent who can leverage African states’ rejection of the Western approach. This is especially relevant as, given Russia’s large domestic demand and production difficulties due to imposed sanctions, it remains questionable whether the country will be able to uphold its position as the leading arms provider to Africa. Aside from this, Russia’s military performance may actually serve as a rather poor advertisement for its defence industry. As such, Africa’s demand for alternative suppliers will likely increase.

The two emerging actors Iran and Turkey have made reference – albeit differently – to the war in Ukraine and its unfolding consequences in order to strengthen their positions in the current world order characterised by Western hegemony. African countries’ rejection of Western agenda-setting has opened new opportunities for both actors to present themselves as the “true brothers” of Africans, ones not tainted by colonial history. Neither Turkey nor Iran is entirely new to dealings with the continent. Turkey’s comprehensive approach to Africa has developed over the last two decades, whereas Iran has shown the inclination to strengthen relations with African states since the 1979 Islamic Revolution. To better understand the recent developments, it is crucial to draw a historical picture of how Iran and Turkey have emerged as external actors on the continent.

Opening to Africa: Two Decades of Turkish Foreign Policy Activism

While Turkish attempts to open up to Africa have proven futile in the past, Turkey has developed a comprehensive, proactive Africa policy since the turn of the century, setting relations with the continent as one of its foreign policy priorities. In this regard, Turkey has employed a multidimensional approach encompassing a wide range of areas, including humanitarian aid; cultural, religious, and educational diplomacy; trade; tourism; and military and security cooperation.

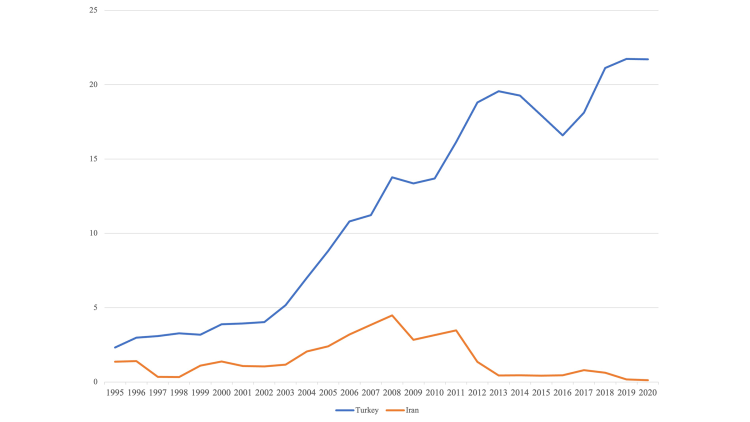

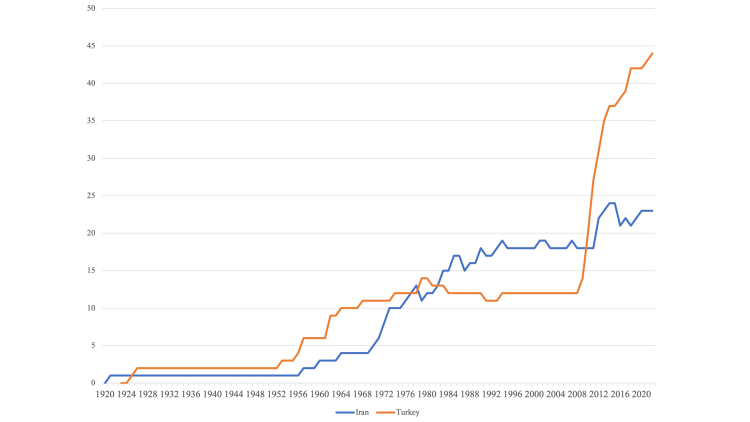

Since the electoral victory of the ruling Adaletve Kalkınma Partisi(Justice and Development Party, AKP) in 2002, the number of Turkish embassies in Africa has increased from 12 to 44, making Turkey the fourth-most represented non-African country on the continent. In fact, no political representative from outside has visited Africa as often as Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, who has been hosted by 31 countries on 52 occasions. Turkey’s opening to Africa truly gained momentum when 2005 was formally designated as the “Year of Africa” and Turkey was granted observer status at the African Union. Since becoming a strategic partner to the AU in 2008, Turkey has organised Turkey–Africa summits on three occasions. Another indicator of the strengthening of Turkey–Africa ties is the total trade volume, which increased from USD 5.4 billion in 2003 to USD 34.5 billion in 2021 (Republic of Türkiye MFA). Upon closer examination, however, compared to other external actors, particularly China, this amount remains relatively marginal. Until the recent rise in Turkish arms sales to Africa, it was only the humanitarian field in which Turkey had emerged as a significant actor in Africa. After the US, Turkey today is Africa’s second-largest provider of humanitarian aid.

Under the AKP, humanitarian diplomacy has become a cornerstone of Turkish foreign policy, with Turkey’s salient involvement in Somalia definitely a case in point. Official political rhetoric regarding the continent builds on tropes of brotherhood and friendship and reiterates Turkey’s non-colonial history and “sincere” commitment to “African solutions for African problems” (Republic of Türkiye MFA). As such, Turkey’s engagement is presented in stark contrast to traditional European actors carrying their colonial baggage and depicted as motivated solely by self-interest, whereas Turkey’s relations with the continent are framed as based on mutual trust and a win–win principle. While humanitarianism has been an essential pillar of Turkish foreign policy towards Africa – and is likely to remain so – the security and defence sector has gained momentum since 2020. Within only one year, Turkish arms sales to Africa bourgeoned, with defence exports rising from USD 82 million in 2020 to USD 461 million in 2021. This trend is most likely to prevail in 2022 – especially amid the Russian war against Ukraine.

Figure 1. Comparison of Turkey and Iran’s Respective Trade Volumes with Africa (in billion USD)

Source: The Atlas of Economic Complexity.

Africa in Iran’s Foreign Policy Calculations: A Historical Backdrop

Iranian leaders have rhetorically referred to the African continent as possessing a “strategic position” in the Islamic Republic of Iran’s (IRI) foreign policy. In effect, however, bilateral relationships with African states have remained largely on the margins. A closer look at the peak periods of Iran’s engagement with the continent offers a formula indicating a separate but interconnected two-fold agenda that the IRI has followed over the past four decades. On one hand, from the years following the 1979 Islamic Revolution, Iran has drawn closer to Africa and stepped back from it several times in its attempts to subvert the drastic international isolation that was meant to debilitate its already ailing economy. In Tehran’s calculations, closer economic-political ties with African states have been crucial to fostering an economic breathing space and forming a voting bloc against the UN resolutions over its nuclear programme and human rights abuses. Between 2005 and 2013, while the core structure of the sanctions regime against the IRI was being formed, the latter established five more embassies across Africa. In 2008 Iran’s trade volume with the continent grew substantially, to USD 4.8 billion – a figure unmatched since.

On the other hand, the less ideologically attenuated group of political-religious forces within Iran – with the supreme leader at the top – view Africa as a solid ground for expanding the “geopolitics of resistance” and furthering the agenda of “exporting the Islamic Revolution.” Given the large Muslim populations residing in Africa, exporting the revolution to African Muslims has been pursued since 1979 – regardless of factional affiliation of the government in power – largely by (para)statal actors who have gradually secured enormous funds to globally propagate Shiism.

With Ebrahim Raisi coming to power, the political landscape displays similarities to the past. Although Iran’s retreat to Africa (see Lob 2022) picked up upon the US withdrawal from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), the new neo-conservative government accelerated the process under the larger foreign policy agenda of shifting to “the East” – materialising in stronger bonds with non-Western states. The systemic and domestic challenges that the IRI is now facing – notably the mass uprisings within Iran and the likelihood of economic sanctions staying in place as the nuclear negotiations move towards unpromising outcomes – in many ways resemble those the country faced during the tenure of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (2005–2013). Iran has tried to evade the sanctions in the past, partly through the African continent, by encouraging African states to, for instance, set up joint banking systems allowing for bilateral trade exchanges, or by leveraging Iranian trade hubs and private, knowledge-based companies abroad. The latter companies were formed to produce local knowledge and chains of production in response to international sanctions in order to make the Iranian economy more “resistant” to economic pressure.

Figure 2. Number of Iranian and Turkish Embassies across the African Continent

Source: Authors’ own compilation.

Turkey’s Unique Position and Growing Importance amid the War

Since the war against Ukraine began in February 2022, Turkey, as a member state of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), has taken on a prominent and unique position as a mediator, seeking to balance relations with both conflict parties. While from the onset condemning the Russian invasion and signalling support for the territorial integrity of Ukraine – even providing Turkish drones to Kyiv – Ankara has simultaneously rejected Western-led sanctions against Russia, increased its trade volume with Moscow by almost 200 per cent, and more recently signalled its willingness to join the Russia- and China-led Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). Throughout this balancing act, Turkey has been applauded by a diverse range of actors for its ongoing diplomacy efforts.

Considering the amplification of food insecurity through the war, Turkey’s role in brokering the grain shipment agreements between the conflict parties has chiefly brought it praise from the international community – not just from the UN and the US but also from Russian president Vladimir Putin, who claimed that if it were not for Turkey’s engagement, most shipments not bound for Europe would have never reached their intended destinations. Having opted out of the agreement only to re-join it, Putin thanked Erdoğan for his efforts in “ensuring the interest of the poorest countries” (Erdoğan cited in Daily Sabah 2022b). Both leaders have criticised the destinations of grain-loaded ships leaving Ukraine, arguing too little was done to ensure they reached those in need. This resonates well with the narrative Turkey has extensively built on over the past two decades to distinguish its involvement in Africa from that of former colonial powers. As such, Turkey’s role in brokering the grain shipment agreement allows it to strengthen its self-narrative as the “humanitarian saviour” (Langan 2017) being genuinely concerned for its “brothers in Africa” (Erdoğan cited in Daily Sabah 2022a).

Following Moscow’s resumption of its participation in the agreement, Putin and Erdoğan announced that they would send grain shipments to Djibouti, Somalia, and Sudan free of charge. The similarities in Russian and Turkish “humanitarian” and anti-Western narratives about the grain shipments seem to be providing a new basis for cooperation in their charm offensives in Africa.

While Ankara’s diplomacy and peace efforts have received considerable attention, the war has ironically also become a real-life promotion space for the Turkish arms industry. Amid the war, Turkish Bayraktar TB2 drones, named after manufacturer Selçuk Bayraktar, Erdoğan’s son-in-law, became globally known. Bayraktar drones’ “effective” showcase in Ukraine– and previously in other scenes of armed conflict such as Libya, Syria, and Nagorno-Karabakh – is likely to attract more customers, a trend which can already be witnessed among numerous African states. While Togo, Niger, and Nigeria are among the most recent buyers, other customers include Ethiopia, Morocco, and Tunisia. The trend of skyrocketing Turkish arms sales to Africa is even more likely to continue after the Africa Aerospace and Defence Expo in September 2022, where Turkey was the biggest exhibitor with 25 companies.

Finally, despite the high competition among arms sellers to African states, Turkey enjoys two major advantages. First, Turkey-produced military equipment such as the TB2 drone is comparably cheaper and requires less extensive prior training, making it especially attractive to less wealthy states. Second, Turkey’s unique position as both a NATO member and a fierce critic of Western engagement with Africa makes it appealing as a potential partner to a wide range of African states.

Turkey’s approach to the African continent mirrors its global aspirations and vision for a new world order. By presenting itself as a humanitarian and benevolent donor and partner, Turkey has been able to create new partnerships, diversify its relations and increase its political leverage towards Western partners. These developments have become increasingly evident amid the war against Ukraine, in which Turkey’s unique position as mediator has increased its international prestige and Western dependency on its diplomacy efforts. On the other hand, Turkey’s callout of global asymmetries – highlighted once again by the war – finds great resonance among African partner states.

Russian Invasion of Ukraine: Boosting Iran–Africa Ties

The Russian invasion of Ukraine, the vacuum resulting from it, and the new emerging global order, coupled with the aforementioned domestic and systemic circumstances, is driving the IRI to re-engage with Africa. The IRI officials claim to have doubled their figures in trade relations with the continent, with up to a 100 per cent increase in exports in 2021. According to the director of Iran’s Trade Promotion Organization (TPO), more than 400 African business delegations have come to Tehran since 21 March 2022 (the beginning of the new year in the Persian calendar, a few weeks into the war). The TPO also announced in August that it had plans to increase its trading hubs across the African continent from three to ten by March 2023 (Tehran Times 2022). These trade hubs have been a crucial facilitator of bilateral trade, which has significantly diminished since the imposition of sanctions on the Iranian export industry. Leveraging these trade hubs, several private economic firms have been able to establish direct trade exchanges with some African states without using mediators in Persian Gulf countries. According to TPO, Iran is now equipping and creating new monetary infrastructure, airline routes, and shipping lines to overcome trade obstacles and increase exports from USD 1.2 billion in 2021 to a planned USD 6 billion by 2026 (FarsNews 2022).

Additionally, mutual African–Iranian commissions are being reactivated, many of which after nearly a decade of absolute silence. For instance, the first Iran–Burundi economic commission was held in August, resulting in seven signed cooperation agreements in domains such as agriculture, mining, investment, and healthcare and medical services. Similar bilateral sparks can be observed largely with regards to Iran’s relations with West African states – cases such as Mauritius, Nigeria, Senegal, and Mali. On his recent Africa tour, Hossein Amir-Abdollahian, the IRI’s foreign minister, announced the signing of a Memorandum of Understanding between Iran and Mali aimed at developing further “comprehensive cooperations.” As part of this framework, cooperative initiatives in defence and “anti-terrorism,” education, and economic fields were deemed necessary by both sides.

In addition to known areas of Iranian engagement with African economies, Iran has more to offer now compared to the past – notably in fields such as the military, information and communications technology (ICT), and certain forms of development assistance. Since the beginning of the war, mutual cooperation in these areas has accelerated. Along this vein, Iranians have renewed efforts for what they call “ICT diplomacy” on the continent, starting with signing mutual cooperation agreements with Nigeria, Gabon, and South Africa. Furthermore, IRI military officials have expressed their willingness to expand Iran’s military industry, particularly through exporting military technology and products to any country deemed a “friend.” Historically, the IRI has militarily supported a variety of different (non-)state actors in Africa, ranging from the liberation movements in the 1980s to arming authoritarian regimes such as Omar al-Bashir’s in Sudan.

The divergence and relocation of Russia’s military resources to the scene of war in Ukraine can prompt marginal arms suppliers to play a bigger role. What could render the IRI’s military products such as drones and rockets – an emerging industry desperately looking to widen its market – more attractive to African customers is their cheap cost. In this vein, amid reports of Russia utilising Iranian drones and missiles against Ukraine, the performance of these military products will be decisive for the future expansion of this industry. However, African states have been reluctant to receive Iranian arms due both to the arms embargo imposed on the IRI and to the grave consequences and costs of flouting US sanctions. This trend will most likely prevail, although if the recent Russia–Iran military cooperation gains dominance, one area of this cooperation could materialise in mutual initiatives to arm the authoritarian regimes in Africa.

All in all, what the IRI envisions gaining from this renewed look towards Africa resembles in many ways what Ahmadinejad and other political decision makers had in mind in the past. Similarly, drumming up political support and pursuing a heightened international status, accessing the rich economy of the African continent, furthering its sectarian agenda, and seeking alternative export markets in the face of existing economic sanctions constitute Iran’s main motivations. Religious parastatal actors would be in a better position to harness the effects of these renewed economic initiatives to spread their brand of Shiism. Since March 2022, these actors have scaled up interactions with countries in West Africa, notably Nigeria among others, to expand what they call “cultural exchanges and cooperations. Forging these ideological-cultural ties with Muslim communities is in line with Tehran’s quest to secure further trade agreements in local settings where there is less competition.

The IRI perceives the current international circumstances – the war against Ukraine and a shift towards multilateralism – as the beginning of a new global order where “the East” envisions a stronger hold for itself on the global order. Unlike the time the Principlists were in power (2005–2013), the fact that Tehran has already sharpened its foreign policy focus towards “the East” could lead to stronger and more prolonged engagement with Africa. Moreover, Iran is now facing the most unprecedented mass uprisings that have ever challenged the political regime. The protests have caused the IRI to use more of its resources to repress protesters and crack down on the demonstrations. The prospect of Iranian uprisings, if not leading to a regime change, could further corrode the country’s already languishing relations with the West and, therefore, drag the government to the African continent to generate a wider space of survival.

While the war against Ukraine has offered a larger window of opportunity for Turkey than for Iran, the changing power dynamics unfolding on the continent – amplified by the polarised response to it – necessitates that the IRI further bolsters its recent re-engagement with Africa. The growing influence of Russia (signalled, for instance, most recently in the coup in Burkina Faso) hints at the rising tendency among some African leaders to cooperate with authoritarian regimes, which would increase the IRI’s potential as a partner.

Iran and Turkey’s Discursive Engagement with Africa: Advocating for a “Fairer” World

The IRI and Turkey (especially under the AKP’s rule) have both deployed an anti-colonial and anti-imperial rhetoric throughout their engagement with African states. In the past, Turkey was the co-founder of a United Nations Security Council resolution ending South Africa’s mandate over Namibia and a founding member of the UN Council for Namibia, supporting its independence, and Iran was among the few countries that supported the African National Congress in South Africa in their fight against the Apartheid regime. The latter fact has been extensively exhibited (and used for leverage) by Iranian leaders as a strong historical symbol to portray the IRI as “the true friend” and “a genuine partner” for African nations. Iranian and Turkish leaders have stressed a discourse of “brotherhood” and “Islamic solidarity,” employing their identities as Muslim-majority countries to make inroads within Muslim communities in Africa and win the hearts and minds of Muslims in Africa. Both Turkey and Iran, along with Saudi Arabia, claim to be the “leaders of the Muslim world” and have competed over Africa against this backdrop through various means. In this vein, Iran and Saudi Arabia have been engaged in geo-sectarian competitions in Africa. West Africa, in particular, has been the scene of the extension of the Iranian–Saudi sectarian rivalry that has intensified the Shiʿa–Sunni cleavages (see Feierstein 2017). Turkey, on the other hand, advocates for its brand of Sunnism as moderate in contrast with, for instance, Saudi Wahhabism (Tepeciklioğlu 2021).

Since the beginning of the war against Ukraine, the West, and particularly the European states, have been accused of holding “double standards” when it comes to the treatment of Ukrainian refugees versus Global South refugees – including Africans. A few days after the Russian invasion, the AU issued a statement asking the Ukrainian government to treat equally the African students who were seeking to escape the war-torn areas. Soon after, the Europeans’ “double standards” and “exceptionalism” towards the crisis in Ukraine became a heated topic in the Global South. For instance, across social media, a vast number of anti-Western sentiments have been observed that are often crystallised in individuals comparing the Europeans’ response to the crisis in Ukraine with crises stemming from other countries, such as Afghanistan.

Figure 3. African States’ Votes on UN Resolution ES-11/1 (“Aggression against Ukraine”), March 2022

Source: Authors’ own compilation.

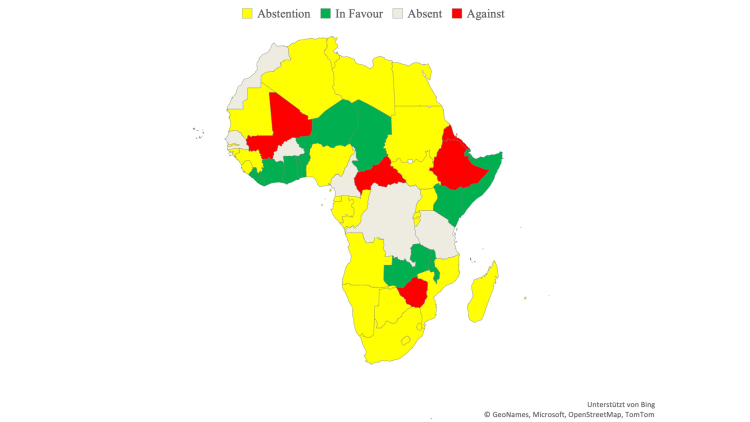

Figure 4. African States’ Votes on UN Resolution ES-11/6 (“Furtherance of Remedy and Reparation for Aggression against Ukraine”), November 2022

Source: Authors’ own compilation.

The votes of African states on a UN resolution on 2 March 2022 condemning Russia’s invasion of Ukraine already showed the Global South’s unwillingness (see Plagemann 2022) – particularly that of African countries – to take sides. Indeed, 26 out of 54 countries in Africa either abstained, did not vote, or voted against the resolution. That figure substantially increased – from 26 to 39 – on a recent UN vote on the “furtherance of remedy and reparation for aggression against Ukraine” on 14 November. This indicates that, as the war continues, the gap between the West and African states remains – and is becoming increasingly prominent. On another occasion, amid a lot of pressure from European leaders on African states to side with the West, President Volodymyr Zelenskyy found the majority of AU heads of state absent from his speech before the organisation in June 2022. While the voting behaviour of African member states has received considerable attention and been met with disappointment from the American and European side (e.g. French president Emmanuel Macron and the US ambassador to the UN Linda Thomas-Greenfield), the 54 African states cannot be thought of as a homogeneous political entity. In the early days of the Russian invasion, Kenya, Gabon, and Ghana strongly condemned Russia’s violation of Ukraine’s territorial integrity. Nonetheless, it is eminent that many prefer not to take sides, which is often read as rising anti-Westernism among citizens and political leaders on the continent. Even the three above-mentioned countries did not support the resolution suspending Russia’s membership in the UN Human Rights Council on 7 April 2022. Altogether, only ten African states voted in favour of that UN resolution.

Iran and Turkey seem fully aware of this changing dynamic. In light of these new developments, Iran and Turkey have not shied away from inflaming these anti-Western sentiments to present themselves as “reliable partners” for their African counterparts. In three consecutive talks with Senegal’s president one week before his official visit to Moscow, Raisi showed Iran’s inclination to renew relations with West African states, saying that Iran “wants Africans for themselves and [unlike Westerners] not for their natural resources” (President.ir 2022). Iranian officials have since stressed this anti-Western rhetoric, insinuating that the West’s only goal in Africa is to “further exploit African nations.” Some have gone as far as to label these Western engagements “neo-colonial” and “racist” initiatives. The same type of rhetoric can be found in official Turkish framing of their engagement with African partners.

Drawing attention to the current global order’s inability to resolve a crisis such as this war, Erdoğan has on multiple occasions in the last months reiterated his famous slogan “the world is bigger than five,” referring to his call for a restructuring of global governance by reforming the UN Security Council. For many years, Erdoğan has been promoting this motto, calling out the injustice of the current global order as detrimental to non-Western and Muslim states. Addressing African heads of state, the Turkish president has presented himself as an advocate for adequate African representation in the UNSC. Overall, he promotes his vision of a new world order under the new motto “a fairer world is possible.”

Challenges for Europe’s Engagement with the Continent

The war against Ukraine is contributing to changing global power dynamics, including the African continent. Both the IRI and Turkey seek to benefit from this power vacuum by highlighting their “genuine” way of engaging with Africa set off against how the West is supposedly treating the latter. Even prior to the war, Europe’s relations with the African continent were marked by deep historical mistrust. With current trends prevailing, this entrenched mistrust cannot be sufficiently mitigated. If European governments, therefore, want to remain relevant partners to African states and contain anti-Western power projection of states such as Iran and Turkey, they should consider the following aspects: First, European governments should not depart from their commitments to the continent: The repercussions of the war for Africa – in addition to preemptive challenges that the continent has long dealt with – should not be downplayed. Humanitarian and development initiatives – many of which were pledged to Africans before the war – should not be suspended as a trade-off for the war. Further humanitarian emergencies and political instabilities resulting from the war will inevitably also affect Europe, in addition to fostering a vacuum for emerging (authoritarian) actors to fill. Second, showing more dedication to horizontal partnerships with African counterparts is key:the European Union should conform to its promises of genuine, horizontal cooperation (e.g. those made during the EU–AU summit in February 2022). In that way, breeding grounds for further anti-Western discourses leveraged by actors such as Iran and Turkey can be limited. Third, a consistent approach towards a value-based foreign policy must be taken: If taking sides with Europe in the war and its normative values is desired, Europe’s own foreign policy should be consistently developed without being perceived as applying double standards. This pertains not only to African states but to the Global South in general. Europe is at risk of losing the support of a great number of states, which is indispensable to containing rising authoritarianism globally.

Acknowledgement

Research for this Focus article was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (German Research Foundation, DFG) – 463159331.

The authors would like to thank Dr. Jens Heibach for his valuable feedback and comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

References

Daily Sabah (2022a), Türkiye Aims to End Russia–Ukraine War through Diplomacy: Erdoğan, accessed 7 November 2022.

Daily Sabah (2022b), Türkiye, Russia Agree to Send Grains to African Countries for Free, accessed 7 November 2022.

FarsNews (2022), Tejarat-e Iran va Afrigha be 5 milliard miresad (Iran–Africa Trade Will Reach 5 Billion), accessed 7 November 2022.

Feierstein, Gerald M. (2017), The Fight for Africa: The New Focus of the Saudi–Iranian Rivalry, Middle East Institute, accessed 7 November 2022.

Langan, Mark (2017), Virtuous Power Turkey in Sub-Saharan Africa: The “Neo-Ottoman” Challenge to the European Union, in: Third World Quarterly, 38, 6, 1399–1414, accessed 7 November 2022.

Lob, Eric (2022), Iran-Africa Relations under Raisi: Salvaging Ties with the Continent, Middle East Institute, accessed 7 November 2022.

Plagemann, Johannes (2022), Die Ukraine-Krise im globalen Süden: kein „Epochenbruch“ (The Ukraine Crisis in the Global South: No “Epoch Break”), GIGA Focus Global, 2, Hamburg: GIGA, accessed 7 November 2022.

President.ir (2022), Ayatollah Raisi in a Meeting with the President of Mozambique, accessed 7 November 2022.

Republic of Türkiye MFA (Republic of Türkiye, Ministry of Foreign Affairs) (n.y.), Türkiye–Africa Relations, accessed 7 November 2022.

Tehran Times (2022), Iran to Establish 7 New Trade Centers in Africa by Mar. 2023, accessed 7 November 2022.

Tepeciklioğlu, Elem Eyrice (2021), Turkey’s Religious Diplomacy in Africa, in: Tepeciklioğlu, Elem Eyrice and Ali Onur Tepeciklioğlu (eds), Turkey in Africa: A New Emerging Power?, New York: Routledge, 199–216.

The Atlas of Economic Complexity (n.y.), The Growth Lab at Harvard University, accessed 23 November 2022.

UNCTAD (2022), The Impact on Trade and Development of the War in Ukraine, accessed 7 November 2022.

Wezeman, Pieter D., Alexandra Kuimova, and Siemon T. Wezeman (2022), Trends in International Arms Transfers, 2021, Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), accessed 7 November 2022.

General Editor GIGA Focus

Editor GIGA Focus Global

Editorial Department GIGA Focus Global

Regional Institutes

Research Programmes

How to cite this article

Demirdirek, Mira, and Hamid Talebian (2022), Bolstering the Bromances: Turkey’s and Iran’s Tightening Ties with Africa, GIGA Focus Global, 6, Hamburg: German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), https://doi.org/10.57671/gfgl-22062

Imprint

The GIGA Focus is an Open Access publication and can be read on the Internet and downloaded free of charge at www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publications/giga-focus. According to the conditions of the Creative-Commons license Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0, this publication may be freely duplicated, circulated, and made accessible to the public. The particular conditions include the correct indication of the initial publication as GIGA Focus and no changes in or abbreviation of texts.

The German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) – Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien in Hamburg publishes the Focus series on Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and global issues. The GIGA Focus is edited and published by the GIGA. The views and opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the institute. Authors alone are responsible for the content of their articles. GIGA and the authors cannot be held liable for any errors and omissions, or for any consequences arising from the use of the information provided.