- Startseite

- Publikationen

- GIGA Focus

- Ten Things to Watch in Africa in 2023

GIGA Focus Afrika

Ten Things to Watch in Africa in 2023

Nummer 1 | 2023 | ISSN: 1862-3603

Russia’s war against Ukraine has accelerated international competition for influence in Africa. Structural weaknesses and post-pandemic instabilities continue to threaten achievements in the fields of democratic governance, peace and security, as well as development. We present a select list and analysis of “ten things to watch” in Africa in 2023.

Politics: Democratic quality will depend on the nature of polls, as the electoral calendar is heavily packed. Important general elections that could trigger social unrest are scheduled in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Nigeria, and Zimbabwe.

Peace and security: Against the backdrop of continued structural-conflict risks, Jihadism and related ethno-regional tensions pose a major security challenge that may spill over to neighbouring states, especially from the Sahel to West African coastal countries. The recent ceasefire in Ethiopia’s Tigray Region could be a first positive step towards peace.

International arena: Amid Russia’s war against Ukraine, many African governments were reluctant to join the international coalition condemning the Putin regime. Continued Western pressure on African countries to isolate Russia fosters African agency. At the same time, we expect to see an intensifying “new scramble for Africa” that includes both China and Middle Eastern countries.

Socio-economic development: African countries will slowly rebound from the COVID-19 pandemic’s socio-economic effects, but high poverty, inequality, and government debt hamper economic growth. Progress on joint efforts to counter the climate crisis remains slow.

Policy Implications

Western support for African countries in their struggle for democracy, peace and security, as well as development requires a “new start” that focuses on prevention rather than ad hoc responses to current crises. The European Union and United States should avoid lapsing into Cold War habits of only assisting African governments if they “break away” from Russia. Germany needs to formulate a sound Africa policy that balances values and national interests with realistic assessments of the policy’s potential in light of bigger players like China.

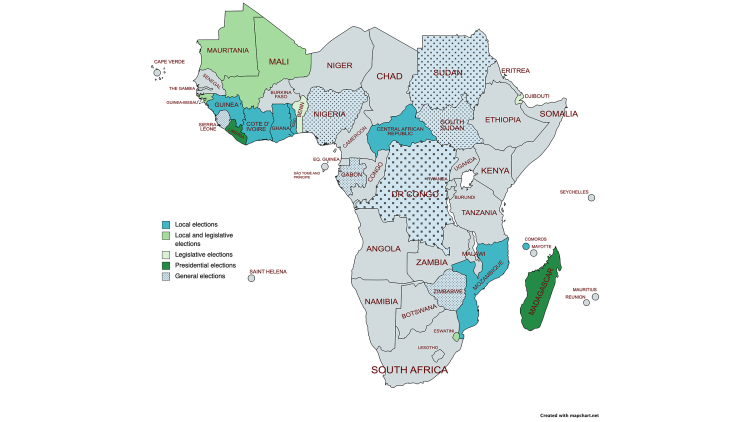

Election Watch 2023: Disinformation on the Rise

Sub-Saharan Africa’s 2023 electoral calendar is a heavily packed one. At least 24 countries are expected to hold elections at various levels of government. This ranges from local elections in Central African Republic, Cote D’Ivoire, Ghana, and Guinea to legislative elections in Benin, Guinea Bissau, and Togo, to presidential elections in some ten countries (see Figure 1 below). Recent trends of disinformation campaigns, electoral misinformation, and the weaponisation of fake news are expected to increase and thus mar some of the upcoming highly competitive presidential polls, especially in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Nigeria, and Zimbabwe.

In the DRC, presidential and parliamentary elections are scheduled for December 2023 according to a road map released last November by the Electoral Commission amid ongoing rebel violence in the country’s eastern region. The incumbent Felix Tshisekedi and his main contender Martin Fayulu, who claimed victory in the 2018 polls, are both expected to run again. Zimbabwe will also witness a repetition of the 2018 electoral constellation with Nelson Chamisa – who denounced widespread voting fraud five years ago and unsuccessfully challenged the polling results at the Constitutional Court – opposing President Emmerson Mnangagwa. Competing parties in Zimbabwe have in the past employed such desperate measures as using paid “online warriors” to manufacture and spread propaganda on Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp. The threat of disinformation could even be more acute in the 2023 election given the recent exponential increase in the use of smartphones, the Internet, and social media.

Among the continent’s population, enduring support for the principles of democracy and yet high dissatisfaction with the practising of it continue to exist side by side. The latest Afrobarometer surveys shows that more than two-thirds of Africans still prefer democracy to any other form of government. At the same time, public discontent with political rulers and institutions as well as corruption and poor public services could lead to further (mass) protest and strikes. Unfulfilled socio-economic promises exemplified by the rising cost of living and greater food insecurity will pose a challenge for incumbents seeking re-election.

Figure 1. Elections in Sub-Saharan Africa in 2023

Source: Authors’ own compilation.

Nigeria: The Looming Danger of Electoral Unrest

The stakes are high in Nigeria’s presidential polls, where incumbent Muhammadu Buhari has reached his constitutional two-term limit. For the first time since Nigeria’s return to democracy in 1999, observers expect a three-way presidential race in a highly tense political atmosphere. Bola Tinubu, the former governor of Lagos State from the ruling All Progressives Congress, is set to compete with Atiku Abubakar, the former vice-president from the main opposition People’s Democratic Party, and with the charismatic Peter Obi of the Labour Party, who is especially popular among the country’s over 12 million first-time voters. Without a sitting president who is able to capitalise on incumbency advantage standing for re-election here, the chances of a tight race and – in contrast to previous polls – even a run-off are high. The elections also constitute the first test of electronic voting and the digital transmission of results, measures introduced via a recently passed electoral law in order to reduce the dangers of vote rigging.

Growing popular distrust in political institutions, deep ethno-religious cleavages, and the highly partisan traditional media could undermine the legitimacy of the elections and escalate tensions in the face of the already-volatile situation found in several parts of the country. Inadequate security will remain a major problem in 2023. The police and army continue to be underpaid and understaffed. The chronic Islamist insurgency in the northeast, the secessionist activities in the south, and the upsurge in organised crime nationwide could intensify further if important triggers like social media abuse, fake news, and disinformation are not kept in check before and after the polls. While the 2023 elections in Nigeria – Africa’s powerhouse – could bolster its democratic quality, they could also set the country on a path of electoral disputation, unrest, and democratic backsliding if digital disinformation and misinformation are allowed to fester.

Multiple Conflict Risks – Prevention Must Combine Security and Development

Violent conflict plagued the sub-Saharan African region in 2022 and will continue to do so in 2023 too. Geographic hotspots in this regard can be found in West Africa and the Sahel, Central Africa, and East Africa. The greatest threat stems from Salafi-Jihadist insurgencies, which have intensified in recent years – especially in the Sahel, the Lake Chad Basin, and the Horn of Africa. From its epicentres in West and East Africa, Jihadism has since made inroads into Southern and Central Africa and is likely to spread further afield again. Attacks were recently recorded in West African coastal countries like Benin, Cote d’Ivoire, and Togo. Jihadism successfully capitalises on inter-ethnic tensions and socio-economic deprivation – and then creates vicious cycles of escalation by worsening existing grievances.

These conflict risks are prevalent in many countries and are intensified by long-term, rather diffuse drivers such as climate change, demographic pressures, weak states, poor governance, and the fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic. Such risks might materialise in various forms, not only full-scale armed conflict, and especially in relation to struggles over political power. Central Africa is plagued by either localised violence in failed states such as Central African Republic and the DRC or by separatist conflicts like in Cameroon. Other conflict risks include anti-government protests, electoral violence, and military coups. The latter are usually informed by a tradition of politicised armed forces and sense of imminent crisis, as exemplified by the recent wave of military takeovers in West Africa and Sudan.

However, far from all African countries will be plagued by violence. The recent ceasefire in Ethiopia justifies the cautious hope that one of the region’s most brutal wars of recent years may have ended. But to translate the current unilateral ceasefire into a more sustainable peace, international engagement will remain necessary. Withdrawing foreign peacekeepers could make things worse. Yet, external support for rival factions within a country – possibly one fallout from the Ukraine War – is a potential driver of escalation elsewhere. Western countries must carefully evaluate and redesign their strategies and support African solutions that combine both security and development. Long-term approaches should prioritise prevention rather than ad hoc diplomacy and rushed military interventions.

The Sahel Conflict and Contagion in the Coastal Countries

The year 2022 was a pivotal moment for European foreign policy in the Sahel. In Mali, the decision to pull out French forces and the announcement of the withdrawal also of European contributors to the United Nations’ MINUSMA peacekeeping mission fundamentally changed the ramifications of the conflict. Nonetheless, this step was politically consequential, given the obstructionism of the military government, its anti-Western populism, and its withdrawal from the G5 Sahel coalition.

In Burkina Faso, the escalating security crisis led to the collapse of the civilian government in January 2022 and to a second military coup in September of the same year. Tragically, the political crisis at the national level played further into the hands of violent extremists by eroding social order and local-governance institutions. People’s desperation is palpable in all segments of Malian and Burkinabé society. With many clinging to any sliver of hope they can, populist manipulation and Russian-led disinformation find fertile ground. Military rulers, failing to live up to their promise of restoring security, still lack the capacity for the all-encompassing internal repression that the Russian government can offer them instead.

Meanwhile, Niger has become the focus of European diplomacy, aid, and security assistance due in large part to the fact that it is the only remaining elected, civilian government in the region. However, Europe’s failures in Mali may repeat themselves in Niger. Security and financial assistance must, then, be based on realistic assumptions and an overarching political strategy (Lierl 2020).

Many of the structural conditions that enable the expansion of violent extremism in the Sahel are also present in the coastal neighbouring countries. This includes pre-existing intercommunal conflicts, opportunities to extract revenues from mining and smuggling activities, the instability of national politics, as well as problematic state–society relations. Especially Benin and Cote d’Ivoire, but also (northern) Ghana, Senegal, and Togo, have all seen an increase in cross-border activities by Jihadists, along with growing domestic recruitment and infiltration. Although there have not been public reports of Jihadist activities in Guinea yet, it should be considered equally vulnerable. However, while the conditions may facilitate contagion, Jihadists’ deciding to take on the state will depend on those governments’ ability to win over local communities.

Going forward, the lesson for Europe’s engagement in Benin, Niger, and the other West African coastal states ought to be a more pronounced focus on state–society relations. With violent extremism having now become a permanent presence, states and societies must become more resilient to it. Security forces and civilian administrations should begin to act in the interests of the most at-risk segments of society. European partners can contribute to this goal by holding their own assistance to this standard too, and by concentrating their political leverage on issues of security-sector reform, anti-corruption, and democratic governance.

Cautious Optimism in Ethiopia Following the Declared Permanent Cessation of Hostilities

In Ethiopia, the civil war between the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) and the Ethiopian National Defense Force continued until a truce agreement was reached in South Africa on 2 November 2022 with support from African Union mediators. Fighting had resumed in August after a “humanitarian truce” proclaimed by Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed and reciprocated by the TPLF in March had broken down. Despite the truce, Tigray had remained under siege and only small amounts of food and medical aid made their way into Ethiopia’s most northern region that borders Eritrea while electricity, Internet, and banking services continued to be largely unavailable.

The renewed fighting involved ethnic Amhara militias with claims to Tigrayan territory as well as the armed forces of Eritrea, where a general call for mobilisation had been issued in September 2022. According to the University of Ghent’s Tigray Atlas of the Humanitarian Situation, the death toll from the civil war was devastating. Up to 200,000 perished from starvation, 50,000 to 100,000 were directly killed, while over 100,000 fell victim to the breakdown of Tigray’s healthcare system (Annys et al. 2021).

According to the November truce, all Tigrayan forces are to be disarmed and, in turn, the federal government will end its siege and restore all interrupted services while humanitarian aid is supposed to flow unhindered. It remains to be seen if the agreement will hold in 2023. One of the problems is that among the four warring parties, the TPLF is the only one supposed to disarm; it is also uncertain whether Eritrean forces will leave Tigray any time soon. The agreement obliges the federal forces to ensure the end of “foreign incursions,” a reference to Eritrea, but it is uncertain if they will be able to do so. Amhara militias also continue to pose a threat. In the coming months, the most important tasks at hand will be to rectify the most devastating humanitarian shortcomings in Tigray, to restore food supplies, and to initiate a process of transitional justice, which undoubtedly will face many hurdles. Widespread ethnically motivated conflicts in the Oromia region are also likely to pose a threat to Ethiopia’s stability throughout the year ahead. Support from the international community will be crucial to securing a lasting peace.

Fallout from Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine – A New Scramble for Africa?

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022 has impacted sub-Saharan Africa in various ways. First, as Russia and Ukraine are major exporters of wheat and fertilisers, the war threatens food security in countries such as Ethiopia and Kenya. Second, the Ukraine War may have substantial – but ambiguous – economic effects. Major African oil and gas exporters might benefit from high prices and demand for energy resources. This positive effect might be offset by lower demand for Africa’s export commodities in a struggling world economy.

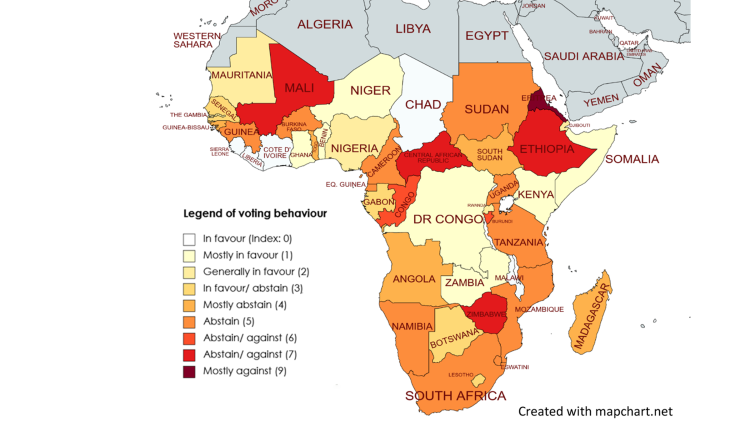

Third, Russia’s aggression has already accelerated competition for influence between the West and non-Western actors. Voting patterns for the five resolutions on the Ukraine War proposed in the UN General Assembly show the respective positions of sub-Saharan African governments. While around half of the countries in sub-Saharan Africa voted in favour of these resolutions strongly condemning Russia, the other 50 per cent abstained; Eritrea, meanwhile, voted against the majority of them. No single factor explains this failure to condemn Russia’s aggression, but one should not underestimate the anti-Western sentiment that may have contributed to such voting patterns. Other reasons include economic and military ties with Russia or China, as the latter also abstained. Authoritarian regimes also tended to abstain, and all governments that either sought military assistance from the notorious Russian “Wagner Group” or are ruled by the military (except for France’s close ally Chad) did not vote in favour of resolutions condemning Russia’s war against Ukraine either. Moreover, former liberation movements now in power in Southern African countries such as Angola, Mozambique, Namibia, and South Africa have historical ties with Russia given it supported their erstwhile anti-colonial struggles. South Africa, for example, did not vote in favour of any of the resolutions condemning Russia, including the one that denounced the annexation of Ukraine territory – even though it has previously declared Ukraine’s territorial integrity “sacrosanct.”

Western governments have increasingly courted democratic but largely abstaining countries like Senegal and South Africa to join the international coalition seeking to isolate Russia. Yet, the latter’s influence in Africa is dwarfed by China’s much greater economic and political muscle on the continent. Moreover, one must not discount the influence of both Middle Eastern countries and other global players such as Brazil or India. This “new scramble for Africa” increases the agency of African governments as they have more choices vis-à-vis cooperation. At the same time, Western countries may fall back into Cold War habits and support governments just because of their favourable orientation, which would undermine the credibility of such engagement. The worst-case scenario would represent the supporting of rival political camps within specific countries, running the risk of fuelling proxy wars like those seen in Angola or Mozambique pre-1989. The West must design an Africa policy that respects African sovereignty and works in the best interest of all partners involved, especially the general population.

Figure 2. African Governments’ Voting Behaviour regarding UN Resolutions on the Ukraine War

Source: Authors’ own compilation.

Notes: Index (0–10) based on voting behaviour of governments in the UNGA on the emergency sessions resolutions (ES 11/1–5). Darker colours and higher values indicate averages of less favourable voting on the resolutions on the Ukraine War (ES 11/1 condemned Russia’s aggression; ES 11/2 condemned the humanitarian crisis caused by Russia; ES 11/3 called for Russia’s exclusion from the UN Human Rights Council; ES 11/4 condemned the annexation of four Ukrainian oblasts; ES 11/5 called for reparations being paid by Russia to Ukraine). Seychelles are not shown on this map, but voted in favour (similar to the continent’s other island states). The foreign minister of Madagascar was sacked after voting against Russia’s annexation of Ukrainian territory.

The German Government’s Evolving Africa Policy

Understandably, in 2022 the new German government’s foreign policy was focused primarily on countering Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and less on Africa. Yet, as indicated above, the war in Ukraine has also affected the relationship between Europe and Germany on the one hand and those two parties and their African partners on the other. When German chancellor Olaf Scholz visited Cyril Ramaphosa in May 2022, South Africa’s president refused to unambiguously condemn Russia’s actions. Nevertheless, both Ramaphosa and Senegalese president Macky Sall were invited as guests to the G7 Summit in Germany in June 2022.

The contours of the German coalition government’s Africa policy have not been spelled out in detail yet. The African continent did not feature prominently in the coalition agreement that was published in December 2021. Among the issues mentioned, the document foresaw further support for the free trade zone AfCFTA and the G20 Compact with Africa, which was set up by Germany’s previous “grand coalition” government. Yet strengthening the private sector seems to find less emphasis now. This is more important than ever though, as the engagement of German business in sub-Saharan Africa remains lacklustre: less than 1 per cent of German direct investment goes to Africa (and mostly to northern African countries and South Africa).

Two ministerial visits at the end of 2022 point to new areas of focus in Germany’s Africa policy. First, Robert Habeck, Minister for Economic Affairs and Climate Action, travelled to Namibia and South Africa to forge cooperation in the production and export of “green” hydrogen. Most certainly, supporting energy transitions and securing new suppliers of sustainable energy will become a hallmark of the German government’s evolving Africa policy. Second, Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock returned 20 Benin bronzes to Nigeria that had been looted by the British during the colonial period. She stated that this would only be the beginning of a larger restitution programme that acknowledges one of Germany’s “darkest chapters of history, namely our own colonial past” (Der Spiegel 2022). These two aspects will most likely also feature prominently in the new Africa strategy that the Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) is developing. It will be released in January 2023, set to replace the “Marshall Plan with Africa” that was unveiled by the previous government in 2017. The latter had been criticised for its “paternalistic” approach to cooperation with African partners (Stiens 2022).

In a clear departure from prior plans, the German government announced that it will withdraw its troops from the military missions in Mali after the country’s elections scheduled to take place in 2024. The Wagner Group has increasingly made inroads there, while Mali’s military government has condemned the presence of France and its partners on the West African country’s soil. Germany’s first national security strategy, slated for 2023, will lay out in more detail the coalition government’s approach to supporting the AU, fighting Islamist terrorism, and nurturing peace and security.

Weathering the Storm, But Economic Risks Remain

Recurrent economic shocks have exhausted the capacity of many African economies to cope therewith. The global economic downturn and international price shocks (that, inter alia, concern food, fuel, and agricultural inputs) have hit several African countries especially hard. Under difficult macroeconomic conditions – extremely high inflation, elevated levels of public debt and debt service, as well as acute pressure on public spending – economic growth slowed down in 2022 to about 3 per cent and will barely recover in 2023. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 22 African countries were either bankrupt or in debt distress by the end of 2022 (McNair and Sembene 2022). Median debt-service costs tripled from 3.4 per cent of government spending in 2012 to 10.3 per cent thereof in 2022. Double-digit inflation rates were very common last year too.

These troubles will not go away overnight, and many countries – such as Mozambique and Zambia – have sought support from the International Monetary Fund, or have extended previous IMF support programmes. Ghana forcefully illustrates these problems, but also the way ahead. Inflation there peaked at 50.3 per cent (year-on-year) in November 2022. Ghana has defaulted on its debt, which stands at more than 100 per cent of its gross domestic product – interest payments accounted for almost half of government revenue in 2022. It is now the recipient of an IMF bailout package worth about 4 per cent of its GDP. Details of the reform programme such as revenue mobilisation and public-enterprise management remain to be seen. Debt restructuring will inflict huge losses on domestic bondholders, including Ghana’s pension schemes and banks, implying substantial risks for 2023’s economic outlook. International creditors will also see their debt cut, but probably by less than domestic ones will. The Ghanian cedi's freefall came to a halt after the announcement of the IMF programme, indicating that international markets are confident that the country will be able to manage the current debt crisis.

Challenges for next year and beyond vary very considerably across the continent because of country-specific vulnerabilities and exposures to risk. Consider inflation and the exchange-rate regimes. Ghana’s temporarily very weak currency has exacerbated inflationary pressures. Meanwhile, the fixed exchange rate (and monetary policy) of the West African Economic and Monetary Union appears to have shielded member states from extremely high inflation. Public debt and high interest rates continue to be a key risk. While Nigeria’s debt levels seem manageable, very high interest payments increasingly eat up too much of government revenue. Some countries remain very vulnerable to global risks such as high food prices, and to local ones including another poor rainy season in the Horn of Africa. Weathering the storm at large will, unfortunately, still mean that 2023 is a bad year for some of Africa’s poorest countries and people.

Climate Change: From Announcements to Implementation?

The “African” COP (Conference of Parties) that was held in Egypt in November 2022 brought little progress in terms of reducing global emissions, but adaptation – long stressed by (vulnerable) developing countries – did receive increased attention. The conference finally produced an agreement on a “loss and damage fund.” It is meant to support developing countries hit hard by adverse climate impacts. How this fund is put into practice should be worked out by a “transitional committee” in the course of 2023 to present practical recommendations to next year’s COP28 in Dubai. Beyond this, there were a couple of announcements of additional adaptation initiatives and pledges, including USD 100 million to the adaptation fund. Regarding questions of climate and energy, Russia’s aggression against Ukraine is more influential than the COPs – this also holds true for Africa. The current energy crisis is leading Europe to seek new sources of natural gas, including through liquified natural gas projects in Mauretania and Senegal. The year 2023 will see more of such contested developments. Further, there is also a push for green hydrogen initiatives. This includes a large project in Namibia via a joint venture with Germany that should start exporting green ammonia in 2026, with a first pilot plant supposed to be completed by the end of 2023.

African Pop Culture Goes Global

With Morocco being, in December 2022, the first African country to ever see its national football team in the World Cup semi-finals, the playing field seems to be levelling for the continent. But sport is not the only arena in which Africa is seeing more success internationally, often driven by diaspora engagement and online platforms. The world’s most successful TikToker is Senegalese-Italian Khaby Lame. Four out of five 2023 Grammy nominations in the “Global Music Performance” category went to African artists, and major Western music labels have opened representations in African capitals. With Western markets largely saturated by now, video-streaming platforms are increasingly targeting African ones instead as well as investing in local content.

Notably, commercial success often goes hand in hand with the improved representation and greater recognition of African artists and stories. Netflix not only produces African content for African audiences, but also delivers Ghanaian social-issue dramas and light-hearted Nollywood comedies to American and European living rooms. After Black Panther paved the way with its all-black cast, The Woman King did the previously unthinkable by successfully selling a plot based on the Agojie – the historic female warriors in the Kingdom of Dahomey – to a worldwide blockbuster audience.

These success stories cannot, however, hide the cleavages that endure both intercontinentally and within Africa itself. Funding is still much scarcer in the latter than elsewhere, with dynamism often linked to the engagement of African-Americans or African diasporas in Europe. Most sub-Saharan artists and content come out of South Africa and Nigeria, leaving a lot of local talent undiscovered (or at least unrecognised). But 2023 could be the year when the playing field becomes a little less uneven. To get the ball rolling, superstar actor Omar Sy’s historical drama Tirailleurs is bringing the story of colonial African soldiers in the French army during World War I to cinemas in both Europe and Africa.

This GIGA Focus deviates from the series’ typical format. It is the joint product of several GIGA Institute for African Affairs staff members. Martin Acheampong and Julia Grauvogel authored the election-watch section and the contribution on Nigeria’s upcoming polls; Matthias Basedau wrote the segments on violent conflicts and the repercussions of Russia’s war against Ukraine; Nicole Hirt examined the ceasefire in Ethiopia. Tabea Lakemann addressed Africa’s pop culture; Jann Lay contributed the parts on economic development and climate policy; Malte Lierl wrote on the crisis in the Sahel; Christian von Soest authored the section on the new German government’s Africa policy. Matthias Basedau and Julia Grauvogel edited this GIGA Focus.

Fußnoten

Literatur

Annys, Sofie, Tim VandenBempt, Emnet Negash, et al. (2021), Tigray: Atlas of the Humanitarian Situation, accessed 14 December 2022.

Der Spiegel (2022), Benin-Bronzen: Baerbock bezeichnet Rückgabe an Nigeria als überfällig, accessed 21 Dezember 2022.

Lierl, Malte (2020), Growing State Fragility in the Sahel: Rethinking International Involvement, GIGA Focus Africa, 7, December, accessed 3 January 2022.

McNair, David, and Daouda Sembene (2022), Why Today’s Debt Crisis Requires a Different Kind of Thinking, accessed 3 January 2022.

Stiens, Teresa (2022), ‚Solidarität und Verantwortung‘: Ampel arbeitet an einer Afrika-Strategie, in: Tagesspiegel Online, accessed 21 Dezember 2022.

Redaktion GIGA Focus Afrika

Lektorat GIGA Focus Afrika

Forschungsprojekt

Regionalinstitute

Wie man diesen Artikel zitiert

Basedau, Matthias, und Julia Grauvogel (2023), Ten Things to Watch in Africa in 2023, GIGA Focus Afrika, 1, Hamburg: German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), https://doi.org/10.57671/gfaf-23012

Impressum

Der GIGA Focus ist eine Open-Access-Publikation. Sie kann kostenfrei im Internet gelesen und heruntergeladen werden unter www.giga-hamburg.de/de/publikationen/giga-focus und darf gemäß den Bedingungen der Creative-Commons-Lizenz Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 frei vervielfältigt, verbreitet und öffentlich zugänglich gemacht werden. Dies umfasst insbesondere: korrekte Angabe der Erstveröffentlichung als GIGA Focus, keine Bearbeitung oder Kürzung.

Das German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) – Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien in Hamburg gibt Focus-Reihen zu Afrika, Asien, Lateinamerika, Nahost und zu globalen Fragen heraus. Der GIGA Focus wird vom GIGA redaktionell gestaltet. Die vertretenen Auffassungen stellen die der Autorinnen und Autoren und nicht unbedingt die des Instituts dar. Die Verfassenden sind für den Inhalt ihrer Beiträge verantwortlich. Irrtümer und Auslassungen bleiben vorbehalten. Das GIGA und die Autorinnen und Autoren haften nicht für Richtigkeit und Vollständigkeit oder für Konsequenzen, die sich aus der Nutzung der bereitgestellten Informationen ergeben.