- Startseite

- Publikationen

- GIGA Focus

- Federalism in Times of Crisis: Insights from India’s COVID-19 Response

GIGA Focus Asien

Federalism in Times of Crisis: Insights from India’s COVID-19 Response

Nummer 3 | 2023 | ISSN: 1862-359X

The COVID-19 pandemic has underscored the significance of empowering local authorities to respond to health emergencies. This policy brief, drawing on a comparative analysis of four Indian states, shows that a successful pandemic response depends on factors such as local governance, community engagement, and decisive leadership.

As India’s federal system has demonstrated, an undue centralisation of authority combined with a decentralisation of responsibility without adequate resources can undermine the efficacy of a crisis response.

Political polarisation can be a formidable obstacle, obstructing coordination and exacerbating the inefficiency of crisis response.

Kerala’s and Odisha’s crisis management during the COVID-19 pandemic has been commendable, with dedicated leadership, coordinated efforts between the respective state and local administrations, and active public engagement contributing to their success.

Despite having a weaker healthcare system, Odisha’s response to the crisis was comparable to Kerala’s, while Uttar Pradesh’s was hindered by uncommitted leadership and polarisation along political and communal lines.

Karnataka, with a stronger healthcare infrastructure than Odisha and Uttar Pradesh, performed only marginally better than Uttar Pradesh, primarily due to a lack of committed leadership, cooperation, and trust across government agencies.

Policy Implications

Decision-makers in federal systems worldwide, and in the European Union in particular, can benefit from studying India’s COVID-19 response. To achieve a successful response, policymakers should prioritise horizontal and vertical coordination and encourage subnational innovation. India’s state-level experiences suggest the importance of leveraging networks between different levels of government and civil society. Key factors for success include strong infrastructure, committed leadership, collaboration across government departments, empowerment of grassroots initiatives, and active community engagement.

Collaboration and Coordination for Crisis Governance

The COVID-19 pandemic has posed unprecedented health, humanitarian, and economic challenges worldwide. In federal systems, it has emphasised the importance of fostering effective vertical and horizontal coordination and of building coalitions across party lines and regions. While federal countries tend to promote cooperation and coordination among levels of government in “normal” times, not all have effectively leveraged the creative potential inherent in successful partnerships during all phases of the COVID-19 crisis. For instance, Germany’s decentralised approach managed to contain the first wave of the pandemic (March to September 2020) but faced challenges during the second wave (October 2020 to April 2021). In part, this was due to complacency, but it was primarily caused by federal politics interfering with pandemic management before parliamentary and state elections in 2021 (Narlikar 2020). Similarly, Canada’s approach, which kept partisan politics out of the crisis response during the first wave as it prioritised recommendations from the scientific community, began to falter during the second wave (after October 2020), as over half of its provinces succumbed to political pressures (Broschek 2022). Despite these challenges, Germany and Canada fared better than the United States, where party divisions significantly impacted public opinion and state governments’ responses to the outbreak (Beramendi and Rodden 2022).

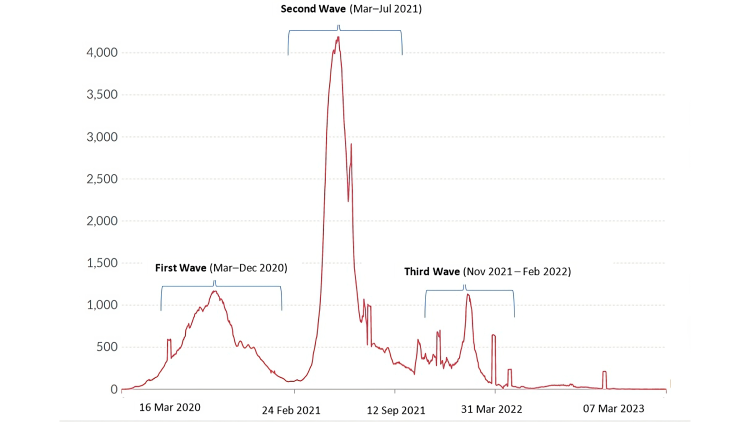

Against this backdrop, this policy brief focuses on India’s pandemic responses, specifically emphasising the first and second waves.The third wave, relatively brief and less deadly, was mitigated by India’s liberalised and accelerated vaccination campaign (Figure 1). In particular, it offers a critical analysis of pandemic experience in India’s federal system by examining four subnational cases. It identifies successful state-level responses and compares them to those that faltered in their pandemic response. The aim is to understand factors that explain efficient COVID-19 crisis governance by certain Indian states but remained elusive to other states.

Figure 1. Daily New Confirmed COVID-19 Deaths in India during the Three Waves

Source: Johns Hopkins University CSSE (various years).

Note: The number of confirmed deaths may not accurately represent the true number of deaths caused by COVID-19.

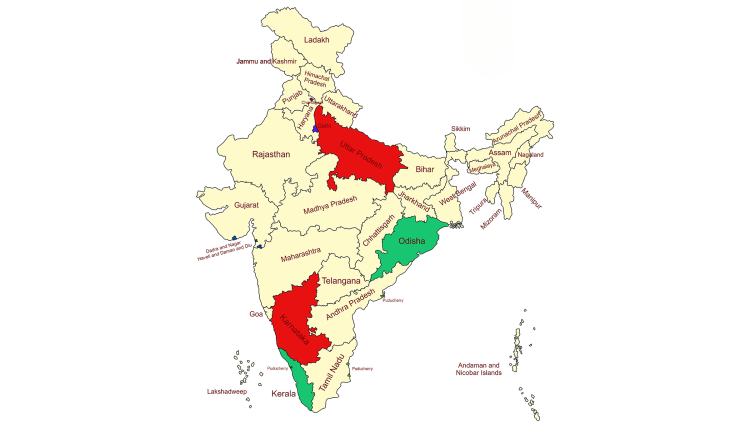

Figure 2. Map of India Highlighting the Four Analysed Cases

Source: Created by author using MapChart.net.

Success Stories: Kerala and Odisha

Kerala

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the critical role of subnational governance in crisis management. When utilised by state and local governments, decentralised institutions can effectively mitigate deficiencies at the national level. Although the realisation of this potential depends on federations having provisions regarding both self-rule and shared rule, the presence of decentralised institutions can still stimulate subnational activism during times of crisis, even in centralised federations where these provisions may not exist. The Indian state of Kerala serves as an exemplary case study in this regard.

Kerala’s successful management of the COVID-19 pandemic has been widely acknowledged (Sneha and Varghese 2021). An extensive examination of the literature and of ground reports from both national and local media sources has yielded a comprehensive understanding of the contributing factors that led to the state’s successful management of the crisis. These include, but are not limited to, high investments in health and education, a robust healthcare infrastructure, a decentralised public health system, a longstanding commitment to extensive social welfare provisions, active community participation in state policies, and a leadership that prioritises crisis preparedness.

Quick Initial Response

Prior to the imposition of a nationwide lockdown, the state government of Kerala instituted measures such as the closure of schools and the prohibition of mass gatherings. Additionally, the state government launched an extensive testing and contact-tracing regime, which was implemented through a network of healthcare workers. Furthermore, the government of Kerala utilised a range of resources, including CCTV cameras, for contact-tracing and isolating individuals.

Thus, the Kerala government proactively initiated containment strategies, surpassing the national government’s response. Subsequently, the Indian national government utilised Kerala’s established methodology as a foundation for its own actions in addressing the pandemic. In addition to carrying out successful containment strategies, the state government of Kerala also prevented the exodus of over 98 per cent of its migrant worker population during the nationwide lockdown period (March to June 2020)by providing them with essential provisions, such as food and shelter. This stands in stark contrast to the disheartening lack of concern displayed by the national government towards the welfare of migrant workers.

Inter-Ministerial Coordination

Kerala’s management of the COVID-19 pandemic illustrates the importance of adopting a collaborative approach in crisis management. The state effectively engaged key stakeholders, utilising their input to implement innovative solutions while drawing upon the state’s own established experience in pandemic- and disaster-management planning. To efficiently monitor, coordinate, and direct on-the-ground efforts, the state established a high-level committee led by the Chief Minister, Health Minister, Chief Secretary, and Principal Secretary of Public Health. The committee was supported by a State Control Room and by various subcommittees.

Decentralised Management

In the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, the state of Kerala implemented a decentralised approach to management, entrusting a significant degree of responsibility to its local self-governments (LSGs) (Rahim and Chacko 2020). The LSGs, the closest government units to the people, were tasked with implementing containment measures within their respective jurisdictions. To facilitate this, LSGs formed partnerships with medical supply stores to ensure medication delivery to homes and provided technical expertise to panchayat (council) leaders through the Kerala Institute of Local Administration. Additionally, the LSGs were also responsible for creating and implementing quarantine protocols, contact-tracing, and other public health measures. The state government provided support and guidance to the LSGs throughout the pandemic.

The decentralised approach adopted in Kerala is noteworthy, as it effectively leveraged the resources and capacities of LSGs. The Kudumbashree initiative, a programme implemented by Kerala’s State Poverty Eradication Mission, played an important role by organising a community network around poverty alleviation and women’s empowerment.

Community Volunteerism

In January 2020, the Kerala government established the Community Volunteer Corps under the Department of General Administration to sustain volunteerism in various societal crises, including the COVID-19 pandemic. This initiative involved the mobilisation of over 350,000 volunteers who provided support at quarantine centres and assisted the elderly. Additionally, the government formed the Arogya Sena, a local squad trained in techniques for containing infectious diseases, in each locality. In response to potential food security issues during the lockdown, community kitchens were also organised and run by the local population (Elias 2021).

Bouncing Back from Complacency for Pandemic Management

Following the declaration of victory over COVID-19 by Prime Minister Narendra Modi in January 2021, a sense of jubilation, accompanied by a certain carelessness, spread throughout the country. This atmosphere was further exacerbated by the scheduling of elections in several states, including Kerala, which prompted vigorous campaigning without adherence to COVID-19 protocols. This lack of vigilance on the part of both the government of Kerala and the population ultimately resulted in a sharp increase of COVID-19 cases during the second wave.

However, upon the resurgence of cases, the Kerala government swiftly regained its footing, leveraging its robust healthcare infrastructure, inter-ministerial coordination, collaboration between state and local governments, and civil society. The government ensured free treatment and medicines in public hospitals and reactivated volunteers, students, and civil society organisations to prioritise preventative interventions, mainly through accelerated vaccination efforts. The state’s efficient detection rate contributed to the effective infection management.

Meeting Oxygen Demands of Neighbouring States

Kerala’s COVID-19 action plan since March 2020 had focused on increasing the supply and storage capacity of medical oxygen to ensure the state could meet its oxygen demand in the future. Thanks to advance preparations, Kerala was able to increase its oxygen production from 50 litres per minute in April 2020 to 1,250 litres per minute in April 2021. As a consequence, while the rest of the country struggled with shortages and inadequate medical oxygen supply during the second COVID-19 wave, Kerala could meet its own demands and even supply oxygen to neighbouring states such as Tamil Nadu, Goa, and Karnataka.

In conclusion, the case of Kerala highlights the importance of inter-ministerial coordination, collaboration between state and local governments and civil society, and a robust healthcare infrastructure in managing the COVID-19 pandemic.

Odisha

Odisha, a state located in the eastern region of India, has been widely recognised for its effective management of the COVID-19 pandemic despite its poor health infrastructure. Under the leadership of its Chief Minister, the state government implemented several proactive measures to curb the spread of the virus and protect the lives of its citizens. Despite not having COVID-mitigation strategies comparable to Kerala’s (Sahoo and Kar 2021), the government of Odisha diligently undertook measures that turned out to be quite efficacious. This is particularly noteworthy in contrast to the abject failure of management in other states, such as Uttar Pradesh.

COVID-19 Hospitals in Each District

One of the key successes of Odisha’s pandemic management has been the establishment of COVID-19 hospitals in each district. This was a crucial step in ensuring that adequate medical facilities were available to treat patients with the virus, and it reduced the pressure on existing hospitals, allowing them to continue treating other patients. The state government also implemented risk-communication interventions to create awareness and promote COVID-appropriate behaviour among citizens. This helped prevent the virus’s spread and protect the most vulnerable segments of society.

Community Involvement

Just like Kerala, Odisha recognised the importance of community involvement and third-tier engagement in the fight against the pandemic. The state’s Chief Minister endowed the heads of village-governing bodies with the powers of magistrates to provide relief and ensure quarantine of migrants returning from big cities due to the unplanned national lockdown. These village heads were also given the freedom to open temporary medical centres based on local needs and were asked to ensure that COVID-appropriate behaviour be followed in their respective villages.

Each village-governing body was provided funds and functionaries to support these efforts. For instance, Accredited Social Health Activist workers and teachers were asked to monitor home isolation cases and support the village heads in pandemic management at the village level. This helped ensure that the people’s needs were met at the grassroots level and that the spread of the virus was effectively contained.

Public–Private Partnerships

During the second pandemic wave, the Odisha government took several additional measures to ensure that the state had adequate medical facilities to treat patients. The government established oxygen plants in the hospitals and collaborated with industries to help produce oxygen. This collaboration forged a template for an effective public–private partnership model for disaster management. The government also formed a task force to strengthen the supply logistics of medical oxygen. As a result, Odisha not only met its domestic demand but also helped many other states suffering from severe shortages of medical oxygen.

Overall, Odisha’s proactive approach, community engagement, and effective use of resources have helped effectively manage the pandemic and protect the lives of citizens.

Failures: Karnataka and Uttar Pradesh

Karnataka

The state of Karnataka, renowned for its flourishing IT sector and progressive policies, appeared to be handling the COVID-19 pandemic competently during the initial days of the first wave. The state initially implemented a 3T approach, which focused on trace, test, and treat methods, and subsequently expanded it to a more comprehensive 5T approach, which included trace, track, test, treat, and technology. Regrettably, despite their initial efforts to control the virus’s spread, the state’s management of the crisis was marred by a lack of coordination, mismanagement, and missed opportunities.

Inconsistencies in Community Involvement and Tracing Efforts

In an effort to replicate the success of neighbouring state Kerala, the Karnataka government mobilised a network of 30,000 volunteers to combat the spread of COVID-19 and assist the most vulnerable. Additionally, 859 NGOs and civil society groups partnered with the government to provide essential sustenance such as cooked food and food rations. During the second wave, the Karnataka government launched an online application form to recruit citizens for on-the-ground or remote volunteering work and created the “Sankalpa” (meaning “Resolution”) portal to coordinate relief efforts efficiently.

However, as the caseload began to surge at the beginning of July 2020, the system broke down due to inadequate communication and coordination among government officials, NGOs, and community leaders. This created confusion and disorder, which led to criticism from Naavu Bharateeyaru, a consortium of NGOs that condemned the government for its inability to manage the pandemic effectively. Therefore, inconsistencies in community involvement and tracing efforts emerged during the second wave, revealing the complexities of managing a pandemic of this magnitude.

Inadequate Healthcare Infrastructure

Although Karnataka has a superior health infrastructure compared to Odisha and Uttar Pradesh, it lags behind other South Indian states such as Tamil Nadu, Kerala, and Andhra Pradesh. Prior to the outbreak of COVID-19, it was widely reported that the state’s low spending on health was a major concern ��– with expenditure on health comprising less than 2 per cent of its GDP. This lack of resources was evident during the COVID-19 pandemic, as both COVID and non-COVID patients struggled to access treatment.

Lack of Inter-Ministerial Trust and Coordination

One of the major shortcomings in Karnataka’s approach was the lack of Kerala-style synergy vis-à-vis enabling conditions and coordinated action. Most importantly, the lack of inter-ministerial trust and coordination led to the failure of the system. As orchestrated by the Chief Minister, the constant shifting or shuffling of top officials and ministers served no other purpose than to cause confusion and lead to mismanagement. Inadequate COVID management was the outcome of this ad hoc approach to pandemic management as opposed to Kerala’s more planned and well-coordinated strategy.

Uttar Pradesh

Dysfunctional Health Infrastructure

A severe deficiency characterises the state of Uttar Pradesh in terms of the basic infrastructure necessary to operate public health institutions efficiently. This is exemplified by the fact that government hospitals in the state are ill equipped to treat even common illnesses such as diarrhoea, a major cause of death in the state. During the second wave,hospitals were overwhelmed and turned away patients, funeral pyres burned round the clock at cremation grounds, and bodies began to pile up at the state’s crematoriums. In an attempt to conceal the true extent of the crisis, the Uttar Pradesh state administration issued orders to private labs in the state to not test people for COVID-19. Multiple studies have revealed that the state implemented a policy of underreporting COVID-related infections and deaths in order to maintain a lower official death count (Ganguly and Mistree 2021).

Uncommitted Leadership and Political Polarisation

The leadership of the state demonstrated an alarming lack of concern for public health, as evidenced by their decision to prioritise political rallies and religious processions over the well-being of the citizens they serve. In the January 2021 elections, despite reports of the highly transmissible Omicron variant circulating in India, the government approved massive political rallies, which exposed citizens to potential health risks. Furthermore, the government held local-body elections in the midst of the second wave, which served as a superspreader event and claimed the lives of hundreds of teachers on election duty (Sainath 2021). The leadership’s disregard for public health was further underscored by their authorisation of the annual Kanwar Yatra pilgrimage in mid-July 2021, even as COVID infections and deaths continued to rise. It was only after the Supreme Court of India intervened and nullified the Uttar Pradesh government’s decision that the pilgrimage was eventually cancelled.

In conclusion,failures have plagued Uttar Pradesh in both COVID-19 management and transparency, evidenced by inadequate testing and underreporting of infections and deaths. The case study highlights the dire consequences of inadequate infrastructure and political leadership prioritising personal, political, and ideological interests over public health and safety.

Federal Crisis Management: Dos, Don’ts, and Musts

When the pandemic struck India, the most significant challenge was preventing the country’s fragile healthcare system from becoming overwhelmed. The task of rapidly increasing the availability of critical care equipment was not only financial but also political. This required a high degree of coordination among government departments and agencies and different actors at all levels of government. This type of coordination and collaboration is achievable in systems such as Germany’s and Canada’s that uphold a political culture which champions the “federal spirit” and subnational autonomy. However, achieving coordination within India’s centralised constitutional framework proved to be a significant challenge in India’s centralised constitutional structure due to the governing party’s endorsement of unitary or unilateralist ideologies and the prevalence of political polarisation.

When the pandemic began in early 2020, the ruling party at the centre, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), adopted a highly centralised approach to addressing the crisis. While other countries in South Asia implemented partial and targeted lockdown measures, India imposed one of the world’s strictest lockdowns, which was announced without prior consultations or planning. This unplanned lockdown resulted in severe economic disruptions and a massive migrant labour crisis while failing to curb the spread of the virus effectively. Moreover, the federal government capitalised on the pandemic as a pretext to centralise fiscal authority, without endeavouring to reinforce intergovernmental coordination mechanisms; particularly, the government could have activated the Inter-State Council, the constitutional entity already in place for this purpose. Consequently, the crisis witnessed a lack of effective coordination. During the second wave, the lack of coordination led to a blame game and chaos. This situation persisted until the Indian Supreme Court stepped in to resolve conflicts and promote greater coordination.

In the midst of a politically polarised environment, certain states have emerged as exemplars in managing the COVID-19 pandemic. The study shows a strong health infrastructure is insufficient for pandemic management. For instance, despite having better health infrastructure, Karnataka performed worse than Odisha in managing COVID-19. The Chief Minister of Odisha demonstrated effective leadership, compensating for the state’s limited health infrastructure. This highlights the critical role of leadership in pandemic management. New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern attracted global attention during the pandemic for acting swiftly and decisively during the pandemic, and German Chancellor Angela Merkel was praised for taking a science-based approach and providing clear and consistent communication to the public during the pandemic.

Table 1. What Factors Contribute to Effective Crisis Management: Insights from Four Indian States

Variables | Kerala | Odisha | Karnataka | Uttar Pradesh |

Health Infrastructure | H | L | M | L |

Committed Leadership | H | H | L | L |

State–Local Coordination | H | M-H | M | M |

Inter-Ministerial Trust | H | H | L | M |

Civil Society Engagement | H | H | M | L |

COVID-19 Crisis Response Rating* | 10 | 7.5 | 3 | 2 |

Estimated COVID-19 deaths during the second wave (1 January to 31 August 2021) | 17,631 | 58,238 | 274,939 | 48,458** (until 30 April only) |

Estimated COVID-19 deaths per 100K during the second wave (1 January to 31 August 2021) | 49.39 | 125.63 | 406.94 | 20.37 (until 30 April only) |

Source: Author’s own analysis and Leffler et al. (2022).

Notes: In light of the widespread underreporting of COVID deaths, Leffler et al. (2022) estimated COVID-19 deaths by subtracting expected deaths (using data from 2015 to 2019) from total deaths during the pandemic.

* H=2, M=1, L=0 (H: “high,” M: “medium,” M-H: “medium high,” L: “low”).

** Uttar Pradesh’s data reportedly had anomalies, and post-April 2021 data was unavailable.

The experience from the four Indian states examined above illustrates that effective and dedicated leaders at the subnational level are characterised by their ability to engage all levels of government and civil society in crisis management processes. They build trust and coordination between state and local governments as well as between ministerial departments, and they inspire people to engage in community-based volunteering.

In order to enhance crisis governance outcomes, the central government must take on a complementary role by coordinating overall strategy, addressing economic costs at the state level, and investing in capacity-building at the local level. Such a collaborative approach, in the sense of “negotiated cooperation” (Sharma and Swenden 2022), was lacking in India’s management of the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, the central and state governments did not make a concerted effort to strengthen local governments’ capabilities, despite the vital role that local governments play during health emergencies. The exact cause for the absence of an all-hands-on-deck approach can be attributed to India’s confrontational partisan federalism, where partisanship forms the primary basis for intergovernmental interactions and informs a culture of competition for political credit and recognition.

India’s experience also shows that overemphasising centralisation or decentralisation, as demonstrated by coordination problems in both the first and second waves, may be unwise. The importance of striking a delicate balance between centralisation and decentralisation is exemplified by Germany’s relative success in combining national coordination with subnational flexibility (Hegele and Schnabel 2021), contrasted with the UK’s coordination failure due to the resurgence of territorial politics in the midst of a top-down governing culture (Diamond and Laffin 2022). France’s highly centralised approach and limited delegation (Or et al. 2021) shares similarities with the approaches adopted by Karnataka and Uttar Pradesh. This type of approach underscores the consequences of top-down yet ambiguous communication, which erodes public trust in governance and hinders community participation.

Overall, decision-makers in federal systems worldwide, and in the EU in particular, can benefit from adopting a balanced approach to pandemic management that prioritises national coordination, subnational flexibility, and horizontal cooperation across jurisdictions. Effective communication strategies, intergovernmental collaboration, committed leadership, and strong infrastructure are critical factors for a successful pandemic response.

Fußnoten

Literatur

Beramendi, Pablo, and Jonathan Rodden (2022), Polarization and Accountability in Covid Times, in: Frontiers in Political Science, 3, accessed 12 January 2023.

Broschek, Jörg (2022), Federalism, Political Leadership and the Covid-19 Pandemic: Explaining Canada’s Tale of Two Federations, in: Territory, Politics, Governance, 10, 6, 779–798.

Diamond, Patrick, and Martin Laffin (2022), The United Kingdom and the Pandemic: Problems of Central Control and Coordination, in: Local Government Studies, 48, 2, 211–231.

Elias, Arun A. (2021), Kerala’s Innovations and Flexibility for Covid-19 Recovery: Storytelling Using Systems Thinking, in: Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 22, 1, 33–43.

Ganguly, Sumit, and Dinsha Mistree (2021), Fragile India, Strong India, in: Foreign Policy, accessed 27 January 2023.

Hegele, Yvonne, and Johanna Schnabel (2021), Federalism and the Management of the COVID-19 Crisis: Centralisation, Decentralisation and (Non-)Coordination, in: West European Politics, 44, 5–6, 1052–1076.

Johns Hopkins University CSSE (various years), COVID-19 Data (Our World in Data), accessed 27 January 2023.

Leffler, Christopher T. et al. (2022), Preliminary Analysis of Excess Mortality in India During the COVID-19 Pandemic, in: The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 106, 5, 1507–1510.

Narlikar, Amrita (2020), The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly: Germany’s Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic, Observer Research Foundation, Special Report, accessed 13 January 2023.

Or, Zeynep, Coralie Gandré, Isabelle Durand Zaleski, and Monika Steffen (2021), France’s Response to the Covid-19 Pandemic: Between a Rock and a Hard Place, in: Health Economics, Policy, and Law, 17, 1, 14–26.

Rahim, Asma Ayesha, and Thomas V. Chacko (2020), Replicating the Kerala State’s Successful COVID-19 Containment Model: Insights on What Worked, in: Indian Journal of Community Medicine, 45, 3, 261.

Sahoo, Niranjan, and Manas Ranjan Kar (2021), Evaluating Odisha’s COVID-19 Response: From Quiet Confidence to a Slippery Road, in: Journal of Social and Economic Development, 23, 2, 373–387.

Sainath, P.(2021), How UP Panchayat Polls, Held Without COVID Protocols, Proved Fatal for Over 1,500 Teachers, in: The Wire, accessed 26 January 2023.

Sharma, Chanchal Kumar, and Wilfried Swenden (2022), The Dynamics of Federal (in)Stability and Negotiated Cooperation under Single-Party Dominance: Insights from Modi’s India, in: Contemporary South Asia, 30, 4, 601–618.

Sneha, P., and Ashwin Varghese (2021), Interpreting Kerala’s COVID-19 Numbers, in: Economic And Political Weekly, 56, 4, accessed 26 January 2023.

Redaktion GIGA Focus Asien

Lektorat GIGA Focus Asien

Forschungsprojekt

Regionalinstitute

Forschungsschwerpunkte

Wie man diesen Artikel zitiert

Sharma, Chanchal Kumar (2023), Federalism in Times of Crisis: Insights from India’s COVID-19 Response, GIGA Focus Asien, 3, Hamburg: German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), https://doi.org/10.57671/gfas-23032

Impressum

Der GIGA Focus ist eine Open-Access-Publikation. Sie kann kostenfrei im Internet gelesen und heruntergeladen werden unter www.giga-hamburg.de/de/publikationen/giga-focus und darf gemäß den Bedingungen der Creative-Commons-Lizenz Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 frei vervielfältigt, verbreitet und öffentlich zugänglich gemacht werden. Dies umfasst insbesondere: korrekte Angabe der Erstveröffentlichung als GIGA Focus, keine Bearbeitung oder Kürzung.

Das German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) – Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien in Hamburg gibt Focus-Reihen zu Afrika, Asien, Lateinamerika, Nahost und zu globalen Fragen heraus. Der GIGA Focus wird vom GIGA redaktionell gestaltet. Die vertretenen Auffassungen stellen die der Autorinnen und Autoren und nicht unbedingt die des Instituts dar. Die Verfassenden sind für den Inhalt ihrer Beiträge verantwortlich. Irrtümer und Auslassungen bleiben vorbehalten. Das GIGA und die Autorinnen und Autoren haften nicht für Richtigkeit und Vollständigkeit oder für Konsequenzen, die sich aus der Nutzung der bereitgestellten Informationen ergeben.