- Home

- Publications

- GIGA Focus

- Rising Anti-China Sentiment Supports South Korea’s Alignment with the US

GIGA Focus Asia

Rising Anti-China Sentiment Supports South Korea’s Alignment with the US

Number 5 | 2023 | ISSN: 1862-359X

The US–South Korea summit in April 2023 showed South Korea’s willingness to further align with the US amid increasing US–China tensions. Statistical analyses show that the increased anti-Chinese sentiment of recent years strongly correlates with public support for alignment with the US. These findings have implications regarding the popularity of the Yoon Suk Yeol administration’s foreign policy.

Polls such as Pew Global Attitudes data published in 2020 show that sentiment towards China has worsened since the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) incident of 2016 and COVID-19’s onset in 2020.

Political orientation played a role in explaining varied attitudes towards China after the THAAD crisis; however, this role decreased after COVID-19’s onset in early 2020.

Analysis of a poll published by Sinophone Borderlands in 2022 shows there is a strong association between negative public attitudes towards China and increased alignment with the US.

These trends affect the Yoon administration’s foreign policy, which has signalled its further alignment with the US amid rising US–China tensions. In December 2022, South Korea announced a new Indo-Pacific strategy that marks a stronger alignment with the US. The emphasis is on a commitment to a rules-based international order, while not completely excluding China.

Given the high levels of anti-Chinese sentiment, it is likely that the Yoon administration will experience increased public support for its foreign policy.

Policy Implications

As a liberal democracy that is increasingly signalling its desire to play a more active role in supporting a rules-based international order, South Korea offers a lot of room for collaboration with Germany and the EU. With its emphasis on “de-risking” relations with China on the rise, the EU can further benefit from collaboration with South Korea in the areas of trade, security, and technology.

Sentiment towards China in South Korea

In recent years, China has become an increasingly thorny issue in South Korea. This is a relatively new phenomenon, one attracting both domestic and global attention. Compared to sentiment towards Japan, which has been driven by the historical legacies of World War II that remain unresolved to this day, public sentiment towards China had been relatively stable previously. After the normalisation of relations in 1992, China was perceived as a harbinger of peace due to the expected role it would play in helping contain North Korea. Also, Sino–Korean relations were perceived to bring mutual benefits via trade due to China’s rapid economic growth. Economic and cultural interaction remains high between the two countries. Today, South Korea is among the world’s most China-dependent economies (Park 2023). Its largest immigrant population is from China, making up 43.6 per cent of all immigrants to South Korea (Lee 2020).

Despite these mutually beneficial relations, a handful of incidents have negatively affected public sentiment towards China since the early years of the new century. These episodes have included controversy over the historical ownership of Goguryeo (Gaogouli), an ancient kingdom that spanned the current territories of central South Korea, North Korea, and northeast China between 37 BC and AD 668. Other conflicts include ongoing disputes over maritime borders around Ieodo (Suyan Jiao) in the Yellow Sea and public disappointment brought about by China’s lukewarm response to North Korea’s shelling of Yeonpyeong Island in 2010. South Korea has made efforts to resolve these issues: on their historical dispute, the country’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs raised its concerns on various diplomatic occasions between 2004 and 2005. Meanwhile, the South Korean government released an official statement that it is against China’s decision to include Ieodo as part of its Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) in 2013, yet China has remained unresponsive on the issue. Despite these stand-offs having aggravated public opinion, and the Yeonpyeong attack and inclusion of Ieodo in China’s ADIZ coming to border on security matters, they have not escalated to the level of diplomatic ties being cut or even military aggression.

The Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) episode of 2016 and onset of the COVID-19 pandemic four years later both helped fuel a sense of grievance towards China among the South Korean public. These issues have not only affected public sentiment; elite narratives have also become increasingly polarised in this context. Regarding THAAD, for example, conservatives and progressives were divided on how to handle the issue: while conservatives argued that THAAD is a necessary deterrent against North Korea and China has no place opposing it, progressives raised the concern that THAAD only benefits the US’s strategic interests and somewhat serves to stoke tensions with China and Russia.

When the COVID-19 pandemic started in China’s Wuhan and spread across the world in early 2020, bifurcated views among political elites revolved around the issue of imposing entry restrictions. Conservatives criticised then President Moon Jae-in and his government for not closing the country’s borders to travellers from China. Regarding the reluctance to enforce border restrictions against the latter, conservatives framed the government as walking on eggshells, unable to take a clear stance in the face of an increasing public health risk. Progressives, on the other hand, pointed out that entry restrictions are unnecessary because the virus’s spread at home was not due to travellers from China but domestic factors. Conservatives, however, further aggravated this polarised stance by criticising the Moon administration for being pro-China (Chosun Ilbo 2020a, 2020b), while progressives warned against the overt politicisation of the issue – pointing out how entry restrictions can increase xenophobia (Hankyoreh 2020a, 2020b).

Public Sentiment Worsens Regardless of Partisanship after 2017

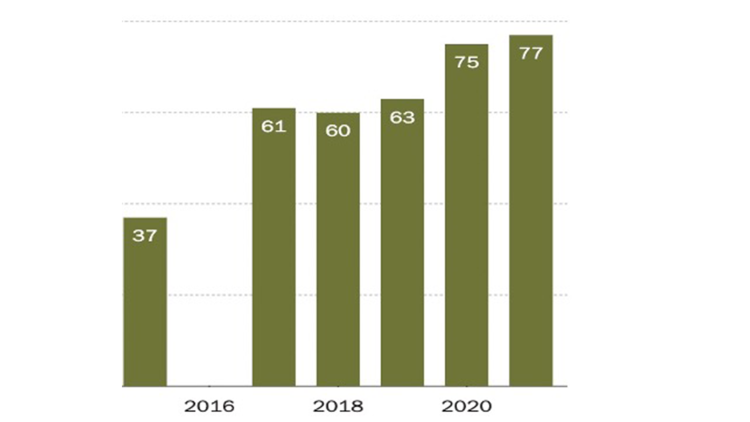

Yet despite divided opinion at the elite level, polls published in the initial period of the COVID-19 pandemic show that the South Korean public’s view on China is worsening overall. Figure 1 below indicates the trends in attitudes towards China reported by the Pew Global Attitudes Project (Silver, Devlin, and Huang 2020). Negative sentiment towards China increased by more than 20 per cent after the THAAD dispute in 2016, and again increased by a further 12 per cent after COVID-19’s onset.

In contrast to polls taken in 2017 after the THAAD crisis, statistical analysis reveals that public opinion is these days less divided along the lines of political orientation. Per Pew Global Attitudes data (Pew Research Center 2018), conservatives are more likely to harbour negative sentiment towards China. Yet the magnitude of the correlation here decreased from 0.13 to 0.06, meaning the difference in attitudes towards China between conservatives and progressives decreased in 2020 compared to two years previously. While gender, education, and income levels do not appear to strongly correlate with negative sentiment towards China, age does. The difference in attitudes towards China between younger and older respondents widened in 2020 compared to 2018. This trend is also consistent with recent findings that the younger generations are more likely to have a negative attitudes towards China in South Korea: out of 14 democratic countries polled (including Canada, Japan, the UK, the US, and some in Western Europe), South Korea was the only one in which youth (ages 18–29) had a more unfavourable view of China than those aged 50 and older: some 80 per cent of South Korea’s youth viewed China unfavourably, compared to 68 per cent of the country’s oldest cohort (Silver, Devlin, and Huang 2020).

Figure 1. Negative Attitudes towards China in South Korea, 2015–2021

Source: Silver, Devlin, and Huang (2020).

Anti-Chinese Sentiment Strongly Associated with Alignment with the US

Although foreign policy is not a salient issue to voters compared to ones such as welfare and public health, researchers have found that in democracies policymakers do care about public opinion when it comes to foreign policy (Maoz and Russett 1993; Schultz 1999). When examining the relationship between attitudes towards China and foreign policy preferences drawing from Sinophone Borderlands polls (Turcsányi et al. 2022), an emerging pattern is detectable: unsurprisingly, the more negatively a respondent feels about China, the less likely they are to support foreign policy alignment with the latter. A one level decrease in the respondent’s favourability towards China leads to a decrease of one point in the 1–10 scale that measures support for alignment with China. Elder respondents were more likely to support alignment with China, while men were less likely to do so compared to women. What is more, the analysis also reveals that more negative attitudes towards China are strongly associated with higher support for alignment with the US. A one level decrease in the respondent’s favourability towards China leads to an increase of 0.39 points in the 1–10 scale that measures support for alignment with the US. These correlations were strong even when controlling for political orientation.

A New Trajectory to the Yoon Suk Yeol Administration’s Foreign Policy

What do these findings imply for the current foreign policy orientation of the Yoon administration? Recent trends show that the latter is leaning towards aligning South Korea’s foreign policy with that of the US. Departing from the “strategic ambiguity” expressed in the first draft of the Indo-Pacific strategy released under the preceding Moon administration, the Yoon government’s Indo Pacific strategy announced in 2022 expresses “strategic clarity” as well as South Korea’s support for allies with regards to human rights and other values. At the same time, the new framework does not exclude China – reflecting Seoul’s priority of maintaining trade relations. The framework also mentions that it is inclusive in nature, meaning it does not exclude China.

Given Seoul’s shift in focus and the waning public support for alignment with China as the desire to move closer to the US grows, it is likely that Yoon’s foreign policy will not be met with a public backlash or hostility for the time being. With negative sentiment towards China existing regardless of political partisanship, elite narratives may also converge. The upcoming legislative elections in 2024 will, then, be a testing ground to see whether elite perspectives converge or remain divided when it comes to China.

Implications for Germany and the EU

The closer alignment with the US’s security framework and recent signalling of support for a rules-based international order indicate that there is greater room for collaboration with Germany on matters of security. Germany and South Korea have continued to work together on supporting Ukraine: on 15 April 2023, South Korea and Germany held talks in Seoul on expanding their humanitarian aid to the country (Song 2023). Germany has taken a strong stance vis-à-vis cooperating with the world’s major democracies in the face of Chinese threats and Russia’s war of aggression in Ukraine, as reflected in the recent G7 foreign ministers’ summit also taking place in April of this year (Klug, Lee, and Yamaguchi 2023). South Korea is one of four countries that are a partner to NATO, with the country recently designating its embassy in Belgium as the diplomatic mission to the organisation, thus signalling its intention to further increase collaboration with NATO on security issues.

A similar outlook regarding the EU–South Korea partnership can be projected. Despite the fractured views on China revealed after French President Emmanuel Macron’s visit to China in April 2023, the EU has stood side by side with the US. Ursula von der Leyen, the head of the European Commission, has not been shy when vocalising disagreement with Beijing on issues of arming Russia, aggression towards Taiwan, and human rights abuses in Xinjiang. Von der Leyen has also called for “de-risking” relations with China. Contrary to the US concept of “decoupling,” “de-risking” refers to the reduction of risks arising from dependencies – particularly on sensitive security issues (Fahrion 2023).

From this perspective, South Korea is an attractive partner when it comes to the EU’s chosen strategy. As a liberal democracy, and one that is increasingly converging with the US on foreign policy, South Korea emerges as a synergetic partner not only in the security arena but also in the economic and technological realms, too. South Korea is home to leading global producers of semiconductors such as Samsung Electronics and SK Hynix, which makes it an important partner when it comes to diversifying related supply chains. Already in 2022, the EU–Korea Digital Partnership was concluded, including among its provisions the increased collaboration on the supply of semiconductors as well as with regards to scientific research and digital innovation. South Korea can be also a prospective partner to the recent US–EU Trade and Technology Council, which seeks to facilitate democratic and market-oriented approaches to trade, technology, and innovation.

The outcomes of the US–South Korea summit that was held in early May 2023 also indicate there is an increasing chance that the US, South Korea, and the EU will align in their views on the China–Taiwan conflict. The joint statement released by the White House and the Blue House noted the two countries’ shared desire to preserve peace and stability in the Taiwan Strait. Such an outlook is likely to find close resonance with the EU’s own perspective – although currently divided, some of the latter’s key figures such as Von der Leyen and Joseph Borrell, the High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, have urged the EU to actively engage with the China–Taiwan conflict (Lau 2023). The emphasis on a rules-based order and democratic values, supporting Ukraine, and South Korea’s shared view on Taiwan as well as on de-risking and decoupling imply that there is high potential for close cooperation and a strengthened alliance between the US, South Korea, and the EU going forwards.

Footnotes

References

Chosun Ilbo (2020a), COVID-19 is Spreading, Government Should Answer Why it is Allowing the Virus to Enter Our Country from China, 19 February, accessed 12 December 2022.

Chosun Ilbo (2020b), Moon Says “the Pandemic Will be Over Soon”, Chu says “U.S. Restriction of Chinese Travelers is Political”, How Can We Trust Them?, 21 February, accessed 12 December 2022.

Fahrion, Georg (2023), How Europe Can Best Stand Up To China, in: Der Spiegel International, 14 April, accessed 30 April 2023.

Hankyoreh (2020a), The Korea Liberty Party Politicizes the Pandemic, is Irresponsible, 29 January, accessed 12 December 2022.

Hankyoreh (2020b), Border Restriction Controversy is Not Appropriate at this Point, 24 February, accessed 12 December 2022.

Klug, Foster, Matthew Lee, and Mari Yamaguchi (2023), ‘No Impunity’: G7 Vows Tough, Unified Stance on Russia’s War, 18 April, accessed 30 April 2023.

Lau, Stuart (2023), Send Warships to Taiwan Strait, Borrell Urges EU Governments, in: Politico, 23 April, accessed 30 April 2023.

Lee, In-Hyuk (2020), 2.52 Million Foreigners Residing in S. Korea. S. Korea is Now a Multicultural Society, in: Korea Economic Daily, 13 April, accessed 12 December 2022.

Maoz, Zeev, and Bruce Russet (1993), Normative and Structural Causes of Democratic Peace, 1946–1986, in: American Political Science Review, 87, 3, 624–638.

Park, James (2023), South Korea’s Enduring Restraint Toward China, in: The Diplomat, 18 February, accessed 30 April 2023.

Pew Research Center (2018), Pew Research Center’s Global Attitudes Project, Spring.

Schultz, Kenneth A. (1999), Do Democratic Institutions Constrain or Inform? Contrasting Two Institutional Perspectives on Democracy and War, in: International Organization, 53, 2, 233–266.

Silver, Laura, Kat Devlin, and Christine Huang (2020), Unfavorable Views of China Reach Historic Highs in Many Countries, Pew Research Center’s Global Attitudes and Trends, 6 October, accessed 30 June 2023.

Song, Sang-ho (2023), South Korean, German FMs Hold Talks on Ukraine, Regional Cooperation, in: Yonhap News Agency, 15 April, accessed 30 April 2023.

Turcsanyi, Richard Q., Tao Wang, Peter Gries, et al. (2022), Sinophone Borderlands Mainland China and Hong Kong Survey, Palacky University Olomouc.

Editor GIGA Focus Asia

Editorial Department GIGA Focus Asia

Regional Institutes

Research Programmes

How to cite this article

Song, Esther (2023), Rising Anti-China Sentiment Supports South Korea’s Alignment with the US, GIGA Focus Asia, 5, Hamburg: German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), https://doi.org/10.57671/gfas-23052

Imprint

The GIGA Focus is an Open Access publication and can be read on the Internet and downloaded free of charge at www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publications/giga-focus. According to the conditions of the Creative-Commons license Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0, this publication may be freely duplicated, circulated, and made accessible to the public. The particular conditions include the correct indication of the initial publication as GIGA Focus and no changes in or abbreviation of texts.

The German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) – Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien in Hamburg publishes the Focus series on Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and global issues. The GIGA Focus is edited and published by the GIGA. The views and opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the institute. Authors alone are responsible for the content of their articles. GIGA and the authors cannot be held liable for any errors and omissions, or for any consequences arising from the use of the information provided.