- Home

- Publications

- GIGA Focus

- Facing the Stress Test: Courts and Executives during the COVID-19 Pandemic

GIGA Focus Latin America

Facing the Stress Test: Courts and Executives during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Number 6 | 2022 | ISSN: 1862-3573

The COVID-19 pandemic’s onset imposed the need for immediate political reactions to protect the domestic population. For some months, decision-making was delegated to the executives while legislatures lost temporary influence. In such a situation, courts have an important role in checking the excesses of executive power.

Latin American high courts decided on a broad range of pandemic-related cases and showed the willingness – when not the ability – to control executives also under the exceptional situation of the pandemic.

Given the region’s long history of intermediate judicial independence, one that is characterised by political interference, many expected such actions would only propel democratic backsliding during the pandemic. However, the active role of courts has largely underscored the continued relevance of institutional checks and balances.

The highest courts were central to keeping in check two illiberal presidents, Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil and Nayib Bukele in El Salvador, albeit with different outcomes. Whereas in Brazil the attempts to undermine judicial autonomy would be unsuccessful (and Bolsonaro eventually lost the electoral contest), Bukele’s party used its majority in the Legislative Assembly to pack the court as soon as it obtained the legislative votes to do so.

Unless presidents have legislative majorities to successfully manipulate an independent court, they rely on informal means of interference such as harsh rhetoric, defamation of judges on social media, or joining demonstrations against these institutions.

Policy Implications

Strong courts that control executives’ power excesses bear the risk of attack by illiberal presidents. During emergencies like the current pandemic, this danger increases given the need for immediate decision-making. To overcome adversity, courts need to find allies in other institutions. Regional and international observers can help if they strongly condemn political interference with judicial independence and publicly denounce attacks against courts that may help undermine democracy.

The Importance of Courts during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Over the past two years of the COVID-19 pandemic, we have seen its severe implications not just for health systems, societies, and economies but also for politics. In Latin America, as elsewhere, the necessary sanitary measures such as lockdowns, stay-at-home orders, or the closure of schools impinged upon basic rights. Although many of these measures were in line with expert recommendations to contain the SARS-CoV-2 virus’s spread, they also provided political leaders with a window of opportunity to bolster executive power, to erode civil liberties, and potentially to undermine democracy (Ginsburg and Versteeg 2021).

In such a situation, courts play an important role in preventing executive abuses of power and protecting rights. To do so, courts need genuine power as well as independence from political actors, as is normally the case in established democracies. In developing democracies, however, courts are frequently contested by other political actors. If they exercise bold control and put a stop to the policies of the executive or the legislature, they may experience both formal and informal political interference. Formal interference may include the impeachment of judges and the appointment of new ones loyal to the president, or reforms that curtail the range of issues on which a court may decide. Informal interference denotes, for instance, public rhetoric against courts or threats of violence against their members. Many courts in Latin America have experienced both formal and informal interference in the past, thereby suffering a loss of judicial independence.

Given this background, whether Latin American courts are willing and able to control the executives, and with what consequences, is an important factor in the quality of any democratic regime regionally. The COVID-19 pandemic put this principle to the stress test, as it demanded immediate and bold decision-making by all institutions in a very short space of time. This situation opened up the chance for either political conflicts or executive abuse, scenarios that arguably could have deepened the risks of democratic backsliding – particularly if executives did not accept to govern in the emergency situation with constraints on their power.

Latin American Courts and the Pandemic

A closer look shows that Latin American courts played a significant role in the context of the pandemic’s onset and subsequent executive responses. We searched on the institutional websites of 14 high courts for decisions related to the pandemic during the period from March 2020 to May 2022. By employing different keywords (“COVID,” “coronavirus,” “pandemia”), we found that courts adopted pandemic-related decisions in all researched countries: some courts decided on hundreds (Brazil, Colombia, Peru) or even thousands (Costa Rica) of cases, but most had at least a dozen COVID-19-related rulings. If we complement this online information with other sources (national and international newspapers, recent scholarly debates, working papers and blogs), we come out with five types of pandemic-related decisions.

First, Latin American courts have decided on individual rights in all countries. These make up the vast majority of all pandemic-related cases and, in many countries, are the only such judicial decisions we found. These rulings may or may not have broader political repercussions but are always important. For example, Latin American courts frequently received claims by prisoners with previous diseases or preconditions who demanded an improvement of their health protection in jail or the possibility of being moved to house detention due to their vulnerable state. Courts mostly did not lift the prison order but did require prison directors or the Ministry of Justice to improve the individual in question’s situation within a certain time frame. One example of a rights case with political repercussions was the ruling in favour of three women in El Salvador who were arrested for violating the pandemic-related curfew. The Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Court declared their detention unconstitutional and ordered the security forces not to deprive anybody of liberty or hold them in the detention centres installed for this purpose. Further, it stated that no person can be detained – only forced to stay at home until the Legislative Assembly issues a law to regulate social mobility during curfew.

Second, courts have controlled the constitutionality of laws or decrees underpinning pandemic policies, thus using the opportunity to limit executive power and to stress the need for legislative participation in these formal responses. The constitutional courts of Colombia, the Dominican Republic, and Ecuador are by constitutional mandate entitled to control every decree that declares a state of emergency (Cervantes, Matarrita, and Reca 2020). Through this automatic control, they have comparatively more opportunities to control government measures than in cases where such a review is not foreseen by the constitution. The most notable role in the review of states of exception during the pandemic was that of the Ecuadorian Constitutional Court, which effectively limited the implementation of the emergency decrees enacted by the president for the management of the health crisis.

Third, courts have also stressed the need for legislative participation in the design of pandemic policies. The El Salvadorean Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Court, for example, issued a range of decisions on individual cases or general claims of unconstitutionality. Again and again, it stressed the need for cooperation between the executive and the legislature in deciding about the length of lockdowns, the possible consequences of their violation, or the reopening of the economy.

Fourth, courts have settled conflicts of competences between different levels of government regarding the management of the health crisis. As a reaction to a new wave of infections in Argentina, in May 2021 President Alberto Fernández ordered the closure of schools in the whole national territory via decree. The mayor of the City of Buenos Aires, Horacio Rodríguez Larreta, questioned that decision and argued that he was the only person legally able to decide on a closure of schools in the city he ruled. The Supreme Court decided in his favour, stating that President Fernández had exceeded his constitutional responsibilities by issuing this decree.

Fifth, courts ordered political actors to adequately respond to the health crisis after its onset. In June 2020, for instance, the Brazilian government desisted from publishing daily information on COVID-19 infections and deaths while also manipulating the publicised data, resulting in apparently lower numbers of deaths. The Federal Supreme Court (Supremo Tribunal Federal, STF) swiftly decided that the government had the obligation to present accurate daily data on COVID-19 on its official webpage.

To sum up, Latin American courts stressed the need to respect individual rights, the limits and duties of institutional competences, as well as for legislative participation in the design of pandemic policies. They also decided on conflicts of competence between different levels of government. Of course, from this regional overview we do not know if courts were not approached in some countries for specific reasons: namely, because people regarded them as politicised or irrelevant regarding the defence of individual rights. However, it is a good sign for the democracies of the region that most courts had to deal with a number of pandemic-related cases; we also saw a range of important checks on executive abuses of power (as in the abovementioned case on the publishing of daily COVID-19 data in Brazil). Hence, high courts in the region by and large can be said to have stood the stress test presented by this health emergency.

Strong Leaders, Strong Courts: A Recipe for Conflict

Most Latin American democracies have a medium level of judicial independence. In 2020, in fact, only Chile, Costa Rica, and Uruguay were classified as having high judicial independence (values of either 9 or 10 in the Bertelsmann Transformation Index 2022). Meanwhile, most courts have been exposed to political interference in the past – from public harassment to the dismissal of disloyal judges. While acting during the pandemic, two cases stood out for having the greatest political repercussions regarding court–executive conflicts: Brazil and El Salvador. In both instances courts exercised bold control and the executives reacted harshly, but the outcomes hereof were very different in the two countries.

Brazil under Bolsonaro

When Jair Bolsonaro (2018–2022), a former army captain and open defender of past dictatorships and far-right values, won the presidency in 2018 he promised to eradicate political corruption and crime and to renew Brazilian politics by undoing the legacies inherited from the leftist Workers’ Party presidencies. His relationship with the STF had already been extremely tense even before taking office. Bolsonaro and his allies frequently depicted STF members as part of a corrupt elite against which he railed with his populist discourse. Further, the institution of the STF itself came under attack. During his election campaign, Bolsonaro’s son Eduardo remarked that to close down the STF would require only “one soldier and one corporal” (Della Coletta 2018).

When the pandemic erupted in March 2020, Bolsonaro contradicted most Latin American presidents by taking a stance that neglected the scientific evidence and refused to protect the population from the spreading virus. He frequently referred to infection as but a “little flu” and attended mass events with his followers without wearing a mask and without maintaining a safe distance. This unwillingness to react adequately to the looming public-health threat resulted in conflicts over policies with the legislature as well as with subnational authorities.

As the federal government was not willing to implement policies to contain the pandemic, governors of individual states decided themselves to introduce measures such as the closure of highways, ports, and airports. This caused a confrontation with the federal government, as Bolsonaro threatened to override the implemented measures countrywide. Within this tense inter-institutional situation, the STF played a central role in controlling the executive and strengthening the authority of other state entities in the management of the health crisis. In one of its most important decisions, in April 2020 the STF decided that the federal government could not override the policies of states and municipalities implemented to protect the population against SARS-CoV-2. Instead, the STF ruled that all three levels of government had the authority to decide about pandemic policies and that a specific sub-unit of government could not rule less strictly than a more stringent law enacted by a superior unit.

A further relevant decision stressing the authority of subnational governments was related to the support of the health system via the provision of the ventilators needed for the care of critically ill COVID-19 patients. In April 2020, the Bolsonaro government tried to confiscate dozens of ventilators bought by the state of Maranhão, which at that time had been severely hit by the pandemic. On the one hand, this move was considered an indicator of the bad state of both public-health infrastructure as well as central-government planning. On the other, it was interpreted as a punitive act by the central government because the state was known for not providing much support to Bolsonaro (Biehl, Pratos, and Amon 2021: 155). The STF ruled in favour of the state of Maranhão, prohibiting the confiscation of the ventilators.

Bolsonaro and his allies reacted to the STF’s bold control with a variety of mainly informal means of interference. The president himself reacted with harsh criticism on Twitter or in public speeches. In April 2020, he joined a demonstration in Brasília where protesters demanded military intervention and the shutting down of Congress and the STF. In June of the same year, his supporters marched outside the court building, threw firebombs, and carried lit torches, in protesting against the STF’s investigation of “fake news” posted about judges on social media. This shows that the STF’s pandemic-related decisions were only one part of the confrontation between it and the executive. In August 2021, Bolsonaro escalated this conflict as he tried to interfere formally with the STF: he sought to start the impeachment process against his main opponent at the court, Judge Alexandre de Moraes, but failed because he lacked a majority in Congress. Even though the latter had one of its most conservative compositions in the country’s history, the STF had gained the respect of many political actors. This was due to the STF’s consequent control of the executive’s actions during the pandemic as well as the expansion of its power in pursuing criminal proceedings against high-rank politicians. This resulted in a “legislative shield” that allowed the STF to fend off the executive’s formal attack on its independence (Werneck Arguelhes 2022).

Bolsonaro’s failed re-election attempt was a further check on presidential authority. A second mandate might have allowed further democratic backsliding, with actual impeachments of judges or an enlargement of the STF – with the new appointments guaranteeing a majority for the incumbent (both these plans were explicitly acknowledged by Bolsonaro and his allies). The broad democratic front that the opposition built behind the presidential candidacy of Lula da Silva stopped this trend in its tracks, however.

El Salvador under Bukele

Nayib Bukele (2019–) became El Salvador’s first president since the end of the 1992 civil war to not be elected as the candidate of one of the country’s two major political parties. In his election campaign, he promoted himself as a break from the traditional elites and the corruption and failures of previous administrations. Similar to Bolsonaro, his main vehicle of communication with the general public has been social media. He defines criminal gangs and the traditional elite as enemies of the people. His Manichean narrative results in a “millennial authoritarianism,” containing “traditional populist appeals, classic authoritarian behavior, and a youthful and modern personal brand built primarily via social media” (Melendez-Sanchez 2021: 21).

Bukele first showed his disposition to authoritarianism when he went to the Legislative Assembly accompanied by dozens of armed soldiers in February 2020. By doing so, he wanted to pressure legislators into approving the loan needed to finance his fighting of criminal gangs. This resulted in two cases being brought against Bukele before the Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Court. The Chamber ordered the president to refrain from using the military for activities that are contrary to its constitutionally defined tasks. Hence, the relationship between El Salvador’s incumbent and the Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Court was already tense even before the pandemic began a month later.

The Bukele government reacted to the health emergency with some of the strictest measures worldwide. Already before a single case of infection had been confirmed within the country, Bukele ordered the closure of schools and borders. At the end of March 2020, his administration implemented a strict curfew that allowed only those working in essential functions to leave their houses to go to work and one person per household to go out to buy food and medicine. The security forces reacted harshly to violations hereof and many people were imprisoned in special detention centres. Early on, the Constitutional Chamber had to decide on the first cases related to the curfew. The decisive one here was the case previously mentioned of three women who were arrested for violating the curfew by going to the local market, which led to a ruling by the Constitutional Chamber that constrained executive power.

At the beginning of May, the government tightened the curfew even further: People were now only allowed to go out to buy food or medicine two times a week, on days defined by their national identification numbers. At this time already more than 4,000 persons had been held in detention centres for violating the curfew. Due to its confrontation with the mainly oppositional legislature, Bukele’s administration governed instead via decrees issued by the Ministry of Health – that is, without a national-emergency law or declaring a state of exception. At the end of May, the legislature voted that the curfew should be lifted to enable informal workers to earn a living. Bukele vetoed that decision, and the conflict was discussed by the Constitutional Chamber together with other complaints against the government’s management of the pandemic. With its decision of June 8, the Constitutional Chamber declared 11 presidential decrees unconstitutional and again underscored the role of the legislature by stating that the suspension of fundamental rights across the entire national territory was not up to the executive but rather the Legislative Assembly.

From early on in the pandemic, Bukele undermined the institutional legitimacy of the Constitutional Chamber: He refused to obey many important rulings and openly defamed the judges as corrupt and as responsible for deaths related to the ongoing health crisis. When the Constitutional Chamber declared the 11 presidential decrees unconstitutional on June 8, for instance, Bukele described this decision on his social media accounts as an order “to murder tens of thousands of Salvadoreans” (Deutsche Welle 2020). By doing so, Bukele created a “hostile narrative” that his social media followers rapidly spread (Indacochea and Rubio Padilla 2021).

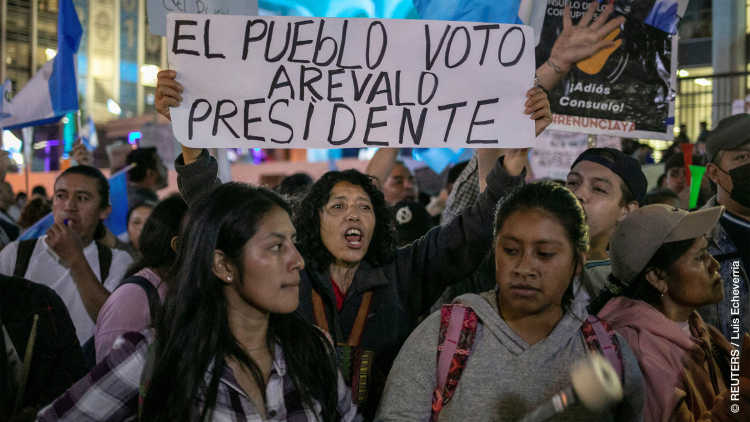

While constitutionally controversial, Bukele’s actions had popular support. Whereas the president had started his tenure with a minority government, in the legislative elections of February 2021 Bukele’s party Nuevas Ideas gained a supermajority. When the new Legislative Assembly met on 1 May, this supermajority of legislators removed the five judges of the Constitutional Chamber from office, legitimising their action on the grounds of the supposed discontent of most citizens with a multitude of “anti-popular decisions” by the Chamber. Further, they accused the judges of “exercising faculties not authorised by the Constitution” by taking on attributes that correspond rather to the executive – especially in health issues. Then, the legislators directly designated five new judges – even though, according to the law, the Legislative Assembly is only allowed to appoint judges from a list of potential candidates pre-selected by the Judicial Council.

With this co-optation of the Constitutional Chamber, Bukele’s supporters not only punished the previous judges for their bold control of the government’s pandemic-management policies. They also paved the way for Bukele’s possible re-election. In September 2021, the new judges ruled that the El Salvadorean Constitution would allow a president to be in office up to 10 years and, by doing so, made his re-election possible. This presents an opportunity for Bukele to consolidate his authoritarian hold on power. With the government, legislature, and courts dominated by the president, and hence working in sync, not only have checks and balances failed but the human rights situation has worsened, too – as thousands of people are increasingly at risk of being prosecuted in a summary, illegal, and indiscriminate manner.

Democratic Backsliding and the Pandemic

The pandemic’s onset required immediate decision-making and action by all institutional actors. This was a context favourable either to clashes between different institutions or to executive abuses, enhancing the risk of democratic backsliding – as has been observed elsewhere, for instance in the case of Hungary (Guasti 2020). In Latin America, the emergency situation of the pandemic had a devastating impact on judicial independence in the case of El Salvador, thus confirming that exceptional situations can be an opportunity for executives with authoritarian ambitions to override the power of constraining actors like courts.

However, illiberal presidents do not always get things their own way, even in emergencies. Both Bolsonaro and Bukele mainly reacted against court controls by means of informal interference, especially by defaming the latter in public or voicing their intentions to interfere with them formally. Only the supermajority obtained in the El Salvadorean legislature after the elections of February 2021 allowed the eventual success of such formal interference.

Public support for the president is a further relevant factor that explains the executive being able to interfere with a court. Bukele enjoys a very high level of backing among the El Salvadorean population. According to a recent survey by the AmericasBarometer (Lupu, Rodríguez, and Zechmeister 2021), 61 per cent of the population think that he is doing a very good job as president. The same survey has shown that in a range of Latin American countries those who support strong leaders tend to be more in favour of weakening the independence of high courts (Driscoll and Nelson 2021). Support for interfering with the independence of the judiciary seems to be especially high among those backing a president who recently clashed with the high court in salient cases and who openly discredits that institution and its members. With strong public support for the president in a sharp inter-institutional confrontation, it was easy for Bukele’s party to weaken El Salvador’s highest court through the removal of judges he rendered as hostile.

How, then, can the region’s courts be said to have fared in the face of the “stress test” of the COVID-19 pandemic? The fact that most Latin American high courts have engaged with a broad range of pandemic-related issues shows that the general public regards them as potential defenders of their rights and as institutional checks on the executive. In the end, it is a good sign for democratic institutions in Latin America that courts, including those confronting authoritarian presidential leaders, have been willing to challenge – and in some cases have successfully checked – abuses of presidential power.

Footnotes

References

Bertelsmann Stiftung (2022), Transformation Atlas 2022, accessed 7 November 2022.

Biehl, João, Lucas E.A. Pratos, and Joseph J. Amon (2021), Supreme Court v. Necropolitics: The Chaotic Judicialization of COVID-19 in Brazil, in: Health and Human Rights Journal, 23, 1, 151–162.

Cervantes, Andrés, Mario Matarrita, and Sofía Reca (2020), Los estados de excepción en tiempos de pandemia. Un estudio comparado en América Latina, in: Revista Cuadernos Manuel Giménez Abad, 20, 179–206.

Della Coletta, Ricardo (2018), Filho de Bolsonaro ameaça STF e diz que para fechar corte basta ‘um soldado e um cabo’, in: El País, 21 August, accessed 7 November 2022.

Driscoll, Amanda, and Michael J. Nelson (2021), Spotlight on Support for Reducing Judicial Power in the Americas, in: Noam Lupu, Mariana Rodríguez, and Elizabeth J. Zechmeister (eds), Pulse of Democracy, Nashville, TN: LAPOP, 90–91.

Deutsche Welle (2020), Corte Suprema de El Salvador prorroga emergencia por coronavirus, 9 June, accessed 5 November 2022.

Freedom House (2022), Freedom in the World 2020-22, accessed 5 November 2022.

Ginsburg, Tom, and Mila Versteeg (2021), The Bound Executive: Emergency Powers During the Pandemic, in: International Journal of Constitutional Law, 19, 5, 1498–1535.

Guasti, Petra (2020), The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Central and Eastern Europe: The Rise of Autocracy and Democratic Resilience, in: Democratic Theory, 7, 2, 47–60.

Indacochea, Ursula, and Sonia Rubio Padilla (2021), Noche oscura para la independencia judicial en El Salvador, accessed 5 November 2022.

Lupu, Noam, Mariana Rodríguez, and Elizabeth J. Zechmeister (eds) (2021), Pulse of Democracy, Nashville, TN: LAPOP.

Melendez-Sanchez, Manuel (2021), Latin America Erupts: Millennial Authoritarianism in El Salvador, in: Journal of Democracy, 32, 3, 19–32.

Reuters Covid-19 Tracker (2022), Latin America and the Caribbean, last update: 15 July.

Werneck Arguelhes, Diego (2022), Weak, but (very) Dangerous: The Bolsonaro Paradox, in: Verfassungsblog, 22 June, accessed 10 August 2022.

General Editor GIGA Focus

Editor GIGA Focus Latin America

Editorial Department GIGA Focus Latin America

Regional Institutes

Research Programmes

How to cite this article

Llanos, Mariana, and Cordula Tibi Weber (2022), Facing the Stress Test: Courts and Executives during the COVID-19 Pandemic, GIGA Focus Latin America, 6, Hamburg: German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), https://doi.org/10.57671/gfla-22062

Imprint

The GIGA Focus is an Open Access publication and can be read on the Internet and downloaded free of charge at www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publications/giga-focus. According to the conditions of the Creative-Commons license Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0, this publication may be freely duplicated, circulated, and made accessible to the public. The particular conditions include the correct indication of the initial publication as GIGA Focus and no changes in or abbreviation of texts.

The German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) – Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien in Hamburg publishes the Focus series on Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and global issues. The GIGA Focus is edited and published by the GIGA. The views and opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the institute. Authors alone are responsible for the content of their articles. GIGA and the authors cannot be held liable for any errors and omissions, or for any consequences arising from the use of the information provided.