- Home

- Publications

- GIGA Focus

- They Should All Go (Again)!: Forty Years of Democracy in Argentina

GIGA Focus Latin America

They Should All Go (Again)!: Forty Years of Democracy in Argentina

Number 4 | 2023 | ISSN: 1862-3573

On 22 October, Argentines will elect a new president, half of the Chamber of Deputies, one-third of the Senate, and a few provincial governors. In a context of rampant inflation, steady poverty, and renewed corruption, the established political coalitions are being challenged by a far-right outsider. Prospects for democracy and the economy look gloomy as Argentina celebrates 40 years of democracy.

In 1983 Argentina initiated the longest spell of democratic life in its history, leaving behind past instability. The country has since overcome its challenges without democratic interruption and, arguably, without seriously affecting support for democracy. Its remarkable achievements also set a global example, such as the 1980s’ military trials.

However, the incapacity to stabilise its own currency in the long run, with monthly inflation reaching double digits since August 2023, has led to disenchantment with politics and politicians. This is giving real chances to Javier Milei, who campaigns against the “political caste,” and proposes to dollarise the economy and close the Central Bank. The slogan “Que se vayan todos!” spontaneously arising during popular protests and riots in December 2001 comes to mind. Then on the streets, now at the polls, anger and disappointment abound.

Argentina is about to test its democratic resilience again. Political cooperation will be necessary to protect democracy and address the economic crisis, which its political parties have been able to offer in the past. Whether, after years of polarisation, they will be up to the task remains to be seen.

Policy Implications

Both Global North and South democracies face serious challenges. Supposedly easy solutions to complex problems see extreme, outsider candidates elected as a breath of fresh air. Their proposals endanger hard-won gains in rights and participation. Ruling elites need to recognise and address people’s real-life problems as well communicate that most of them cannot be solved with quick fixes.

On Sunday 22 October, Argentines will go to the polls to elect a new president, as well as half of the Chamber of Deputies, one-third of the Senate, and a few provincial governors. This is the tenth consecutive presidential election within the longest spell of democratic life in the history of the country, one that began on 30 October 1983 with the election of President Raúl Alfonsín (1983–1989) and put an end to 50 years of political instability, weak democracies, authoritarian projects, and successive military coups. The 2023 elections commemorate, then, 40 years of uninterrupted democratic rule. However, the prospects for democracy and the economy look gloomy in what should be a year of civic celebration.

In fact, the elections are taking place in a context of rampant inflation, with the monthly rate reaching double digits in August 2023 (and the annual one 124 per cent). The poverty rate, meanwhile, reached 40.1 per cent in in the first half of 2023 (INDEC n.d.). No wonder that people’s concerns in the electoral race are mainly about the economy and that disenchantment with politics and politicians is giving a real chance to an anti-establishment, far-right presidential candidate for the first time. The slogan “Que se vayan todos!” (“They Should All Go!”) that spontaneously arose in the country during the popular protests and riots of December 2001 comes to mind here. Then on the streets, now at the polls, people are expressing their anger and disappointment.

It is certainly a limp performance by a democratic regime that, back in the 1980s, took office with promises of improving everyone’s living conditions vis-à-vis increased participation and genuine political competition. The incapacity to stabilise their own currency and to eradicate the pernicious impact that inflation has on the poor and on less-advantaged sectors of society obscures the achievements of a political regime that set a global example on other fronts, such as the remarkable trials of military officers for crimes against humanity in the early 1980s. Throughout these 40 years, Argentina overcame serious threats and challenges without democratic interruption and, arguably, without seriously affecting support for democracy. The question is whether the country will continue to show such formidable resilience at its forthcoming economic and political crossroads.

Two Crises but Democracy at Last

When Alfonsín, from the Radical Civic Union, was elected president, Argentina was concluding the most tragic chapter in its modern history – a military regime with a legacy of state terrorism, an armed conflict with the United Kingdom, and a bankrupted state, high debts, and chronic inflation. Alfonsín campaigned reciting the preamble of the Constitution and promising that under democratic rule Argentines would be able to eat, heal, and get educated. In this way, the Radical candidate defeated Peronism, or the Justicialist Party, the popular party founded by Juan Domingo Perón that had not been defeated in free elections since its foundation in the 1940s.

Alfonsín encouraged a unique policy of human rights reparation and military trials for crimes against humanity that caused unease among the armed forces and led to uprisings. But the policy ultimately became a pillar of the newly established regime and helped draw the military away from politics. The economy would instead prove the unbeatable challenge for the president. Inflation, which averaged 300 per cent during his term in office, skyrocketed to 3,000 per cent during Alfonsín’s last year of rule. The president resigned six months before finishing his six-year mandate in the middle of a hyperinflation phase that led to a dramatic episode of social turmoil, including deaths. He handed over power to president-elect Carlos Menem (1989–1995, 1995–1999) instead through a political arrangement. Peronism was back and here to stay for the next decade. Menem’s governing style made him a typical example of delegative democracy in those years (O’Donnell 1994), which included the excessive taking of unilateral decisions and institutional abuse (remarkably, court packing). However, after an uncertain economic start, the strategy that his administration developed to rein in inflation eventually bore fruit and thus achieved consensus across party lines.

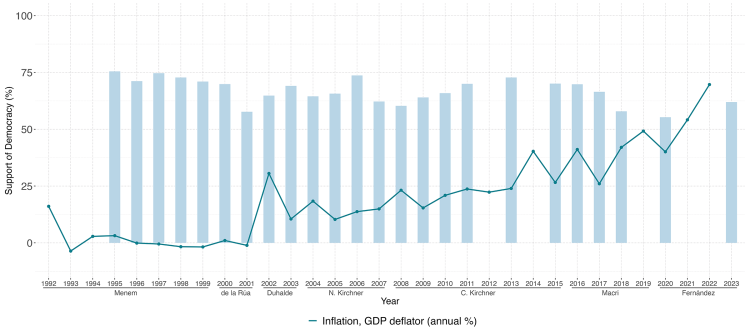

Figure 1 below depicts the annual inflation rate since 1992, marking the first double-digit rate recorded since the hyperinflation episodes of 1989/90. In fact, in 40 years of democratic rule, a single-digit annual inflation rate was only witnessed under the “Convertibility Plan” adopted in 1991 during Menem’s first term. The Plan, approved by Congress to enhance commitment and show self-discipline, created a convertible currency on a one-peso-to-one-dollar basis, and required that the Central Bank had reserves to completely cover the monetary base. The Plan quickly generated the conditions for economic recovery and growth, which enhanced popular support and facilitated a constitutional reform that allowed Menem’s re-election in 1995.

Figure 1. Inflation and Support for Democracy across Presidencies (1992–2022)

Sources: The World Bank (several years); Latinobarómetro Corporation (several years).

Notes: Latinobarómetro data only available from 1995, and missing for years left blank.

However, preserving convertibility became a straitjacket after a few years. It again exposed the Argentine state to recession, fiscal deficit, and a growing public debt. The population suffered from increasing unemployment and poverty due to the adjustment and privatisation measures that accompanied its preservation.Desperate attempts to save convertibility occurred under Menem’s successor, Fernando de la Rúa (1999–2001), with whom the Radical Party returned to power – this time in coalition with other forces, and with the promise to improve accountability but also to maintain the convertibility scheme. However, the extraordinary economic hardship that the latter demanded and the eventual imposition of the corralito,namely restrictions on cash withdrawals in the face of a bank run, undermined political commitment to convertibility.

The last months of 2001 were a tragedy that included a wave of food riots and protests accompanied by fatalities, with thousands of people blockading roads and bridges throughout the country, banging pots and pans in the main plazas of Buenos Aires, and de la Rúa’s resignation. Protesters held all state institutions and political parties equally responsible, inducing a major crisis of representation from which the governing party would emerge the most damaged. In fact, Congress appointed subsequent caretakers to the presidency – all Peronists – to finish de la Rúa’s term. Of them, only Eduardo Duhalde managed to obtain broader, interparty support to stay longer and to implement a pathway out of convertibility amid a context of high poverty, unemployment, returning inflation, as well as all sorts of both internal (protestors, savers, banks) and external (creditors, IMF) pressures. He eventually also resigned and called early elections, taking place in April 2003.

In view of the first 20 years since transition, Argentina became an obligatory reference point in the comparative literature on presidential breakdowns (Llanos and Marsteintredet 2010), the form of political instability prevailing in Latin America during the third wave of democratisation. Minority governments, economic adversity, and social protests could provoke political instability, but presidential interruption did not see the fall of the democratic regime, as used to happen in the past. Further, the paths out of the two crises involved instances of interparty cooperation that temporarily replaced the adversarial politics of normal times. It is striking that, despite these subsequent crises that left Argentina much more impoverished, deeply unequal, and politically disenchanted, support for democracy did not decline significantly. Indeed, the lowest values registered by Latinobarómetro (Figure 1) would be 57.5 per cent in 2001 and 55.3 per cent in 2020 – values still above the regional average.

Political Competition Is Alive, Inflation Too

The critical 2001/2 context and the difficult path of removing the peso–dollar peg initially tamed redistributive demands, while the call for early presidential elections in April 2003 opened up an institutional means to channel discontent. The transitional government led by Duhalde handed out power to his ally, President Nestor Kirchner (2003–2007), with surprisingly balanced state accounts, a growing GDP, and an economic plan put into motion. Still, the president won the elections in a fragmented and competitive environment, obtaining only 22 per cent of the vote (Table 1).

Table 1. Presidents of Argentina (1983–2023)

President (% of votes) | Party | Term | End of Presidential Term |

R. Alfonsín (51.75) | Radical | 1983–1989 | Resignation |

C. Menem (47.51) | Peronist | 1989–1995 | Completed |

C. Menem (49.94) | Peronist | 1995–1999 | Completed |

F. de la Rúa (48.37) | Radical | 1999–2001 | Resignation |

A. R. Saa–E. Duhalde* | Peronist | 2001–2003 | Resignation |

N. Kirchner (22.25)** | Peronist | 2003–2007 | Completed |

C. Fernández de Kirchner (45.29) | Peronist | 2007–2011 | Completed |

C. Fernández de Kirchner (54.11) | Peronist | 2011–2015 | Completed |

M. Macri (51.34)*** | Republican Proposal | 2015–2019 | Completed |

A. Fernández (48.24) | Peronist | 2019–2023 | About to be completed |

Source: Author’s own elaboration.

Notes: Alfonsín (1983) and Menem (1989) were elected through an electoral college vote. Direct presidential elections were adopted with the 1994 constitutional reform. *Elected by Congress to complete de la Rúa’s term (Rodríguez Saá, just stayed for a week); **% of the first round of votes due to Menem’s withdrawal from the second round; ***% of the second round of votes.

Inflation returned with the pathway taken out of convertibility. It remained moderate, though, for about the next ten years. During Kirchner’s mandate, the economy grew at a remarkable pace. True, Argentina’s recovery was possible with the tailwind coming from the international arena, particularly regarding the financial relief provided by high commodity prices and low United States interest rates, a tendency that favoured the entire Latin American region. When the heating economy began to push prices up, the president made a crucial choice: he de-authorised a restrictive monetary policy that would have slowed down growth immediately. In other words, the president prioritised his immediate need to build up his own base of political support over taking an unpopular decision that could, however, have made growth sustainable in the long run (Novaro, Bonvecchi, and Cherny 2014: 158–163).

With the impetus generated by the economy, Kirchner restored the presidential authority damaged by the 2001 crisis and improved his own. He gathered aligned groups within and outside Peronism under the new label “Frente para la Victoria” (“the Front”), which he seduced with progressive decisions, both non-economic (impeachments against Menem’s Supreme Court judges, strong moves to resume trials against crimes of the dictatorship) and economic (public-salary increases, control of the prices of public services, wide-ranging regulations, nationalisations). Thus, Kirchner moved most of Peronism away from the neoliberal, marked reforms of the 1990s and made it attuned to new times – those of the pink tide, or the left-leaning leaders now governing throughout Latin America (Hugo Chavez, Evo Morales, Lula da Silva). This successful move brought political stability back, as well a new era of Peronism. The Front ruled for 12 consecutive years – first under Kirchner, and then under his wife, President Cristina F. de Kirchner (2007–2011, 2011–2015).

The political game saw opposing coalitions form, which eventually led to an alternation of power. On the one hand, the Kirchners created a “popular” pole to embrace those who supported them. These were tied together with a confrontational political discourse of “us and them,” the latter labelled as the “right” (actually, all adversaries). The latter included political parties, but also state institutions (remarkably, the courts) or social actors (the media, entrepreneurial corporations) opposed to or critical of the government’s actions. The coalition was extremely centralised and personalised under the figure of the president. Checks and balances suffered, as they had done under Menem in the 1990s, but could not be dismantled.

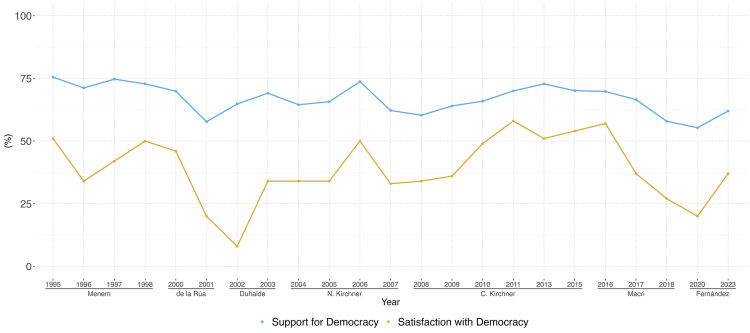

On the other hand, the opposition organised under Mauricio Macri (then Mayor of the City of Buenos Aires), in the alliance Cambiemos or later Juntos por el Cambio, which included Macri’s Republican Proposal (created in 2005) as well as the old Radical Civic Union and other smaller political forces. It leaned to the centre-right, embraced a market-friendly programme, and promised to repair not only kirchnerismo’s mistakes regarding the economy (first disregarded inflation, then also slowing growth) as well as its poor record in terms of corruption and crime. Macri became president in December 2015 with 51.4 per cent of the vote in the run-off election, defeating the Front in a close victory (48.6 per cent). The margin of victory was also slim at the congressional and provincial levels. The ideological shift to the centre-right revived people’s hopes, seeing satisfaction with democracy increased above the 50 per cent mark (see the year 2016 in Figure 2 below).

Figure 2. Support for Democracy and Satisfaction with Democracy (1995–2023)

Source: Latinobarómetro Corporation (several years).

Notes: Answers are to the questions: “Is democracy is preferable to any other form of government?” and “Are you (very) or (quite) satisfied with the functioning of democracy?”

However, the degree of satisfaction quickly declined again. Macri did not deliver on the economic front, not least because of the end of the commodity boom and the volatile international economic situation he faced. His government re-opened the economy, relaxed export taxes, reached a pending agreement with creditors, and removed subventions to public services, while simultaneously trying to avoid a harsh adjustment. The latter eventually came in 2018, arriving hand in hand with an agreement reached with the IMF per its “zero deficit” lending conditions. Argentina was now not only inflationary but also indebted. Macri lost the re-election contest. In October 2019, the Front was back in the presidency with the Alberto Fernández–Cristina Fernández de Kirchner ticket. The COVID-19 pandemic’s onset in 2020 further worsened economic conditions, the country’s GDP fell abruptly, economic privations deepened, and political scandals reared their head once more. An awkward executive setting of a weak president and a strong and radical vice-president who would block sensible economic decisions saw serious missteps taken that would ultimately lead to triple-digit inflation for the first time in 30 years.

Anti-Incumbency and Outsiderism

A crisis of representation has both the attitudinal aspects that people express in opinion polls and the behavioural aspects that they show in the streets (Mainwaring 2018). In the last few years, Latin America has demonstrated its malaise via widespread protests, an anti-incumbency trend, and the election of outsiders (Llanos and Marsteintredet 2023). Interestingly, protest-keen Argentina did not itself see the extended wave of demonstrations that swept the region in 2019 to object to the worsening social conditions accompanying dwindling economies. Instead, it voted the incumbent coalition out in 2015 and 2019 and elected the opposition one in. Voters had balanced options and power alternation was possible. As in other countries, the pendulum swings and electoral punishment of ruling parties went to both the right and left, being more revealing of voter dissatisfaction with government performance than genuine ideological preferences.

Outsiderism had also been a regional trend Argentina itself managed to escape. General distrust in mainstream parties and disenchantment with politics, as the disruptive Latin American context showed, became in many cases the breeding ground for populist discourses and opened the door to extreme candidates or ones who gain traction with promises of resetting the whole system. True, there have been several outsiders in recent Argentine history. Menem and Kirchner themselves had not come from the established party elite when they made it to the presidency. But they still belonged to the great Peronist family. A presidential outsider looks rather like Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro (2019–2022), the right-wing backbencher who praised the military dictatorship and became head of state in 2018 with promises to undo the progressive policies adopted during the Workers Party’s years in government.

The time for outsiderism eventually came to Argentina in 2023, as became evident during the obligatory primaries (known as the PASO) held in August.The PASO settle parties’ internal competition and determine which candidates and tickets each will present in the upcoming general election. On this occasion, 30.2 per cent of the vote went to the far-right populist Javier Milei, with the opposition Juntos por el Cambio coming second (28.27 per cent) and the governing coalition (now called Unión por la Patria) third (27.16 per cent).

Milei lacks robust political organisation for his support base, counts as his only political experience being a congressman since 2021, and did very badly in the multiple provincial elections held throughout 2023. However, in the PASO he managed to voice the frustration and anger of seven million Argentines with an extravagant style and discourse that especially seduced young voters on social media in speaking to exactly what they are fed up with: inflation and politicians. He stresses that the whole political offer, who he names the “political caste” and qualifies as parasitic, corrupt, and useless, is guilty of tanking Argentina’s economy.Looking back to the 1990s, he proposes a liberal economic programme with cuts in expenses and taxes as well as privatisations; he has also announced plans to stabilise the economy through dollarisation and the closing of the Central Bank. The implementation of such radical ideas would certainly bring Argentines back to the street.

But Milei’s proposal is more than just that. His presidential ticket with Victoria Villaruel has touched upon the until now unquestioned pillars of Argentine democracy – namely, its accomplishments on human rights – by holding that “state terrorism” is just a political label. This was articulated by paraphrasing – during the first presidential debate – what dictator Emilio Massera had said in the military trials. Milei also attacked other progressive democratic victories such as the abortion law – which, he claims, subverts and destroys the concept of “family.”

With the parallel dollar rising with no apparent limit, the exchange-rate gap widening, and the threat of hyperinflation looming, the electoral contest is full of uncertainty. As for the August primary results, the three candidates each have a chance of victory. Milei’s presence has not only been disruptive for the electoral campaign. It has already altered the terms of Argentine electoral competition as we knew it until now. His ability to unmask rhetorically the major shortcomings of the established political offer, especially but not only of kirchnerismo in government, appeals to disenchanted voters and may be confounded with a genuine alternative. Experiences elsewhere in Latin America, further to the ones Argentina itself has had over these 40 years, warn us of the risks in installing a radical executive, with scarce institutional resources, under the most adverse economic conditions.

Looking Ahead

Argentina is a case of democratic resilience. It is striking that, without being able to respond consistently or satisfactorily to people’s demands, this democracy has overcome serious crises and periods of hardship, while people’s support for democracy has been maintained or restored. Further, at the most critical moments (the two major crises in 1989 and 2001), the established parties delivered while cooperating to find a way out. It could be that, at that time, the recently accomplished transition to democracy and the painful memories of the military regime worked as an incentive to find creative solutions that prevented a return to the past. Likewise, biannual elections and power alternation may have also helped to channel popular discontent. Indeed, favourable international conditions have proved necessary to (temporarily) fix the economy. The hope is that these conditions will emerge again soon.

Argentina is about to test its democratic resilience once more. Subnational elections occurring throughout the year have already shown remarkable anti-incumbency trends. On the bright side, this shows that democracy is alive and its mechanisms are working. At the national level, though, the presidential elections have become more challenging with the burden of galloping inflation giving real chances to a radical, anti-establishment candidate. If the three-way race holds on 22 October, no presidential ticket will get more than 45 per cent of the votes. In this case, the Constitution disposes that race continues in a second round (to be held on 19 November) between the two most voted-for tickets. Even though surveys are not very reliable these days, they indicate that Milei is currently leading and would thus reach an eventual second round.

Argentina is adding another layer hereby to its long history of embracing risks. Previous experiences with extreme candidates in the region do not foresee a positive outcome when they reach the presidency. Either they become upset with checks and balances and initiate autocratisation from inside state institutions, or they miserably fail – thus stirring political instability, something that Argentina knows all too well from its troubled past. The two possibilities are foreboding for democracy and their overcoming requires democratic commitment. Political cooperation will be inevitable in light of the further economic problems looming on the horizon. It might also be necessary to protect democracy and to devise democratic solutions, something that Argentine political parties have been able to deliver when needed. The question is whether, 40 years after transition and given the many years of extreme polarisation experienced, they will actually be up to the task.

Both Global North and Global South democracies are undergoing hardships and facing serious challenges. Gains in rights and participation are under threat. In this difficult context, ruling elites need to recognise and address people’s real-life problems as well communicate clearly that most of them cannot be fixed with easy promises and quick solutions. The established parties may have made serious mistakes, yet opting for extreme and unexperienced candidates is ultimately merely a shortcut bringing great adversity one step closer.

Mariana Llanos thanks Leon Rademaker and Eduardo Ryo Tamaki for their excellent research assistance.

Footnotes

References

INDEC (no year), Estadisticas, accessed 12 October 2023.

Latinobarómetro Corporation (several years), Latinobarómetro, accessed 12 October 2023.

Llanos, Mariana, and Leiv Marsteintredet (2023), Introduction: Latin America in Times of Turbulence, in: Mariana Mariana, and Leiv Marsteintredet (eds), Latin America in Times of Turbulence. Presidentialism under Stress, New York: Routledge.

Llanos, Mariana, and Leiv Marsteintredet (eds) (2010), Presidential Breakdowns in Latin America, New York: Palgrave.

Mainwaring, Scott (2018), Introduction, in: Scott Mainwaring (ed.), Party Systems in Latin America. Institutionalization, Decay and Collapse, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1–14.

Novaro, Marcos, Alejandro Bonvecchi, and Nicolás Cherny (2014), Los límites de la voluntad, Buenos Aires: Editorial Ariel.

O’Donnell, Guillermo (1994), Delegative Democracy, in: Journal of Democracy, 5, 1, 55–69.

The World Bank (several years), World Bank Open Data, accessed 12 October 2023.

Editor GIGA Focus Latin America

Editorial Department GIGA Focus Latin America

Research Project

Regional Institutes

Research Programmes

How to cite this article

Llanos, Mariana (2023), They Should All Go (Again)!: Forty Years of Democracy in Argentina, GIGA Focus Latin America, 4, Hamburg: German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), https://doi.org/10.57671/gfla-23042

Imprint

The GIGA Focus is an Open Access publication and can be read on the Internet and downloaded free of charge at www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publications/giga-focus. According to the conditions of the Creative-Commons license Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0, this publication may be freely duplicated, circulated, and made accessible to the public. The particular conditions include the correct indication of the initial publication as GIGA Focus and no changes in or abbreviation of texts.

The German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) – Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien in Hamburg publishes the Focus series on Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and global issues. The GIGA Focus is edited and published by the GIGA. The views and opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the institute. Authors alone are responsible for the content of their articles. GIGA and the authors cannot be held liable for any errors and omissions, or for any consequences arising from the use of the information provided.