- Startseite

- Publikationen

- GIGA Focus

- From Ending War to Building Peace – Lessons from Latin America

GIGA Focus Lateinamerika

From Ending War to Building Peace – Lessons from Latin America

Nummer 1 | 2022 | ISSN: 1862-3573

While the recent Taliban takeover in Afghanistan sparked new debate about peacebuilding, Latin American experiences have largely been ignored in such discussions. These could be instructive, particularly in their shortcomings, missed opportunities, and violent backsliding. Colombia five years into the peace agreement and Central America more than 25 years after the end of war hold important lessons.

Ending the civil wars in Central America had been amongst the first empirical tests of the liberal peacebuilding approach. However, today the region is confronting old problems in new forms: increasing authoritarianism, social exclusion, and high levels of state and non-state violence.

The peace process in Colombia remains entangled between those forces pushing for the implementation of the agreements’ transformative agenda and those who staunchly resist it.

International actors such as the United Nations and the European Union actively supported the termination of wars. However, they delegated the structural reforms necessary for conflict transformation to the political systems.

Peacebuilding is possible through a variety of pathways and is a long-term endeavour. It needs to be based on context-specific combinations of violence reduction and prevention, conflict transformation, and political and social inclusion.

Policy Implications

Latin America and other post-war societies tend to receive decreasing international attention after wars have ended and initial post-war elections have taken place. At the same time, there has been a shift in emphasis from peacebuilding to stabilisation at the international level. But peacebuilding requires long-term international support beyond short-term interventions. Latin American experiences show how short-term success can be forfeited through the re-creation of path-dependent developments, which reproduce old problems in new forms. Neither peace nor democracy is feasible without transformative reforms and an inclusive social basis.

After the end of the Cold War international actors such as the United Nations and the European Union became active supporters of negotiated ways of war termination. Over the last three decades peacebuilding policies have expanded to include democratisation, state-building, and fundamental institutional reforms. The retreat of the international mission from Afghanistan and the return to power of the Taliban raised a set of thorny questions about both the feasibility of external interventions and the international peacebuilding agenda. Although Latin American experiences provide important lessons on shortcomings in international approaches, missed opportunities, and persistently high levels of violence after the end of war, they have been widely neglected in this debate.

Liberal Peace in Central America

During the 1980s Central America, like Southern Africa and Southeast Asia, was a global hotspot in the confrontations of the Cold War. Washington, Moscow, and Havana each perceived the civil wars in Nicaragua (since 1977), El Salvador (since 1980), and Guatemala (since 1982) as a battleground to increase or maintain its own influence in the region. When in 1983 Central America came close to a regional war, this danger led to an intensification of the initiatives for mediation and good services that were already underway. Neighbouring countries – Mexico, Panama, Colombia, and Venezuela – established the so-called Contadora Group. While this did not end the internal wars it shifted the focus to their root causes: a lack of political participation, widespread repression by the state security apparatus and aligned paramilitary forces, and high levels of social inequality. On 8 August 1987 the presidents of five Central American countries signed the Arias Peace Plan (United Nations 1987). This opened the door to internal dialogue in Nicaragua and to mediation processes in El Salvador and Guatemala, first led by the Bishop’s Conferences, subsequently taken up by the United Nations.

While the specific content and modes of war termination differed, all civil wars came to an end and the respective armed oppositions demobilised. Differences manifest in the transformation of armed groups into political parties and the establishment of transitional justice mechanisms (see Table 1). In Nicaragua a “transition protocol” between the revolutionary Sandinista government and the opposition was signed and elections held in 1990. The Sandinistas accepted electoral defeat and a coalition of civilian opposition forces took over. In El Salvador a comprehensive peace agreement between the Frente Farabundo Martí para la Liberación Nacional (Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front, FMLN) and the government was signed in Mexico in 1992. Elections including candidates from the former guerrilla groups were held in 1994. While the FMLN’s political support in elections continued to increase, it took their presidential candidates 17 years to succeed. Last but not least, in Guatemala the guerrilla group Unidad Revolucionaria Nacional Guatemalteca (Guatemalan National Revolutionary Unity, URNG) and the government signed a peace agreement in 1996. However, the URNG was not able to transform itself into a meaningful political party. All over Central America the United Nations, the Organization of American States, the European Union, and the United States supported these out-of-war transitions, monitored the demobilisation of the former guerrilla groups, and observed and validated the first elections.

Table 1. Transitions out of War

Source: Author’s compilation.

While the signing of the peace accords in each case was an important step, most of the reforms associated with them were delegated to the respective political system. The prevailing assumption was that the newly included representatives of the former armed groups (or, in the case of Nicaragua, the political opposition) would advocate and press for broader structural reforms. However, those changes were difficult to pursue and all but impossible to achieve. In all three countries the war-time constitutions remained in force. Similar to many countries transitioning out of authoritarian regimes, traditional elites were able in this way to maintain their political and economic power. In El Salvador the right-wing Alianza Republicana Nacionalista (Nationalist Republican Alliance, ARENA) governed the first two post-war decades. In Guatemala different coalitions of economic and military elites have kept control over key positions of power even today. Nicaragua was a somewhat different case, as the Sandinistas lost the elections not only in 1990, but again in 1996 and 2001, though they returned to government in 2006 and have held on to power since then.

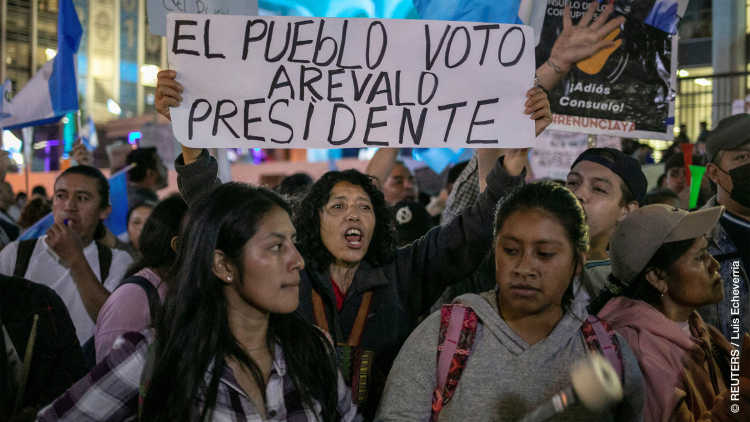

While none of the three countries relapsed into war, the structural problems remained unresolved. Except for Nicaragua, violence shifted from the political arena to society. During the 1990s violent youth replaced former guerrilla groups in discourses on enemies undermining essential reforms in the security sector. The new civilian police forces in El Salvador and Guatemala were understaffed and underfunded, and thus unable to cope with increasing homicide rates. In both countries, governing elites (including the FMLN presidents in El Salvador from 2009 to 2018) emphasised repressive security policies, which dominated public discourse and had demobilising effects on civil society actors. In 2018 Nayib Bukele, a former FMLN member who was expelled from the party, was elected president of El Salvador. In 2021 his newly founded party Nuevas Ideas gained a two-thirds majority in parliament. On his Twitter account Bukele describes himself as the “coolest dictator,” “imperator,” and, recently, even as the “CEO” of El Salvador. Nicaragua took a pathway back to an authoritarian (family-dominated) regime after the first re-election of Daniel Ortega in 2006. The electoral process of 2021 was blatantly manipulated, and most regime critics are either in jail or in exile. Guatemala’s civil society is somewhat stronger than those of Nicaragua and El Salvador. In 2015 a broad protest movement led to the resignation of President Otto Pérez Molina on corruption charges. But civil society has been unable and somewhat unwilling to organise a parliamentary alternative to the highly personalistic and reform-opposing parties.

As this brief overview shows, despite variation, none of the countries has tackled the structural root causes of violent conflict. Democracy manifests mainly in elections, civil liberties are endangered, and the rule of law is in decline (see Figure 1). Poverty and social inequality remain high, and what progress has been achieved in reducing it is being acutely endangered by the COVID-19 pandemic in the form of shrinking economies and rising levels of unemployment, especially for youth and women (Figure 2 and 3).

Figure 1. Key Democracy Data, 1990–2020

Source: All data in Figure 1 from V-Dem 29 December 2021 (Coppege et al. 2021).

Figure 2. Poverty Rate in Per Cent (USD 5.5 2011 PPP)

Source: World Bank 2021.

Figure 3. Inequality (Gini Index)

Source: World Bank 2021.

Colombia’s Entangled Peace Process

Colombia’s experiences in peacebuilding evince similarities but also important differences vis-à-vis those witnessed in Central America. Like Guatemala and El Salvador, the war between the Colombian government and Latin America’s oldest guerrilla group, the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, FARC), ended with a comprehensive peace agreement following a multi-year negotiation process in Havana. However, differences with Central America can be observed regarding at least four elements:

International actors played a comparatively minor role in the negotiations, acting rather as guarantors (Cuba, Chile, Venezuela, Norway) and a group of friends rather than as drivers or official mediators. All Colombian actors involved emphasised that the negotiations were a process amongst Colombians.

Colombia’s war and patterns of violence exhibit a more complex array of armed actors. Guerrilla groups, right-wing paramilitary groups, and organised crime operate in the territory alongside – and challenging – the state’s security forces as well as fighting amongst themselves and against civilians. Colombia has a war economy based on drugs, illegal mining, and a variety of other profitable incomes. This not only blurs the boundaries between war and other manifestations of violence and between legal and illegal patterns of enrichment, but also serves as an important source of political corruption and clientelism. While the government of Juan Manuel Santos (2010–2018) signed a comprehensive peace agreement with the FARC in 2016, other armed actors continue to fight for territorial control and economic resources.

Prior to the accord with the FARC, Colombia had experienced a set of peace processes with mixed success. In the early 1990s some armed groups demobilised and transformed into political parties such as the Movimiento 19 de Abril (19th of April Movement, M-19), while other peace processes such as the one in Caguán (1998–1999) were a total failure, leading to the escalation of violence. Nevertheless, in many of the peace processes demobilised combatants were murdered. In the mid-1980s over 3,000 members, representatives, and candidates from the Unión Patriótica (Patriotic Union, UP), a political party of former FARC members, were killed. The M-19 faced similar violence in the 1990s.

In contrast to other post-war countries, Colombia adopted a new and progressive political constitution as early as 1991. This opened legal and political space for the protection of human rights and non-violent actors within civil society. While the judiciary is part of contested politics, the legal framework of the constitution has safeguarded the peace accord of 2016 and some important reforms.

Five years after signing the peace agreement, three years into the government of Iván Duque, and almost two years since the pandemic hit, Colombia’s peace is in limbo. The current government of the Centro Democrático led the “no” campaign in the referendum on the peace accord in 2016 but could not overhaul the agreement. Nevertheless, implementation of planned measures significantly slowed. This applies most of all to the provisions regarding the modest agrarian reform and the voluntary eradication of coca crops. The most dramatic development is the increase of violence, with a growing number of assassinations of social leaders, human rights defenders, and ex-FARC combatants in some regions. The unit for the analysis of the Special Jurisdiction of Peace has documented 904 assassinations of social leaders and 292 of former FARC members since the signing of the peace accord (JEP 2021). The NGO Instituto des Estudios para el Desarrollo y la Paz (Institute of Studies for Development and Peace, INDEPAZ) documents a return to war-time practices with a growing number of massacres – 90, with 320 victims, in 2021 alone (until December 13) (INDEPAZ 2021).

The patterns of ever more localised violence and the contentious process of the peace accord implementation are clear signs of the entanglement of politics at different scales and between networks of actors promoting or resisting profound transformations. The main topics of contentious politics are related to the deeply engrained structural problems such as around the control and use of land, recognition of citizenship, and coping with past atrocities (Birke Daniels and Kurtenbach 2021). While it is common to hear Colombian colleagues state that “peace is dead,” “peace has collapsed,” or “peace is not a priority, but stabilisation is,” there is little doubt that the pandemic intensified the negative trends already visible prior to its arrival. The upcoming elections for parliament and president in 2022 will be decisive for the fate of the historic peace accord. Due to the high level of fragmentation of Colombia’s party system prospects are rather dim, although in their public statements most candidates endorse the implementation of the peace accord. The relevant question is whether this means just sticking to a minimalist formal implementation or more fundamentally taking up the agreement’s transformative agenda while keeping the violence against reform actors at bay.

Latin American experiences clearly show that the window of opportunity for profound transformation closes rapidly after the end of war. In Guatemala the lost referendum on constitutional change in 1999 (three years after the signing of a peace agreement) was a turning point. In El Salvador it was the broad amnesty law in 1993 that rendered other reforms impossible. In Colombia the lost referendum in 2016 cast its shadow even before the signing of the revised and final agreement. On the positive side a rights-oriented legal framework and constitution in Colombia seem to be enabling important civil society advocacy that favours change and peace agreement implementation. What does this mean for international peacebuilding agendas?

International Actors’ Focus on War Termination

Since UN Secretary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali published the Agenda for Peace in 1992, the United Nations and the European Union have actively supported the negotiated termination of many civil wars in the Global South. El Salvador served as a blueprint for the liberal peace paradigm not only in Latin America but also in many other regions such as Southern Africa, Southeast Asia, or the Balkans. Although there have been variations related to the specific local conflicts and contexts, the main assumption was that war termination serves as a first step, and democratisation should follow, as a democratic regime would serve as the main mechanism of conflict transformation. In the ideal case people would vote for parties and representatives according to their interests and needs, and the democratic governments would then pursue policies to transform the underlying grievances and problems.

However, empirical evidence of this working is scarce in Latin America. According to the sixth regional report on human development in Central America (ERCA 2021), the region is currently facing its worst economic, political, and social crisis of recent decades. The progress made has been too scattered or too little to overcome the historically engrained problems and reverse the negative developments of recent years. Politics and institutions are part of the problem and not the solution, as surveys on regime preferences and trust in institutions show. While the majority of people in the Central American post-war countries and Colombia still prefer a democratic government, the percentage of respondents that do not care or would rather see an authoritarian government solve their problems has increased; those with little or no trust in the government comprise a majority today (Latinobarómetro 2021). This could prove a breeding ground for the reproduction of various forms of violence, exclusion, and emigration.

Similar developments can be observed in other regions. In the Balkans, the Dayton Peace Agreement of 1995 ended the war with a power-sharing agreement. While accommodating the most relevant actors the agreement lacked a transformative perspective and cemented ethnic identities. In a recent report on the peace agreement’s implementation, the international high representative, Christian Schmidt, stated that the country faces “its greatest existential threat of the post-war period” as the Bosnian Serbs strive for independence and Bosniaks and Croats have not been able to agree upon electoral system reforms (United Nations 2021). Mozambique, where armed conflict restarted 20 years after the end of war in 2013, and Northern Ireland, where Brexit gave new importance to the border between the UK and Ireland, are other examples showing the fragility of peace agreements even if war does not resume.

In the face of the evident problems on the ground the United Nations, in a review of international peacebuilding architecture, broadened its agenda from a focus on post-war countries towards sustaining peace and called for an integrated approach “uniting the peace and security, human rights, and development ‘pillars’ of the UN” (United Nations 2015: 11). Similar approaches can be observed at the bilateral level that promote “whole-of-government” or “network” approaches. While this signals some progress, traditional preferences persist on the ground, favouring sequential approaches (stability first) and emphasising military and heavy-footprint interventions. Why is this problematic?

Academic and political criticism of the liberal peacebuilding approach problematised early on the lack of local ownership in top-down approaches to war termination and in Western blueprints for reform (Mac Ginty and Richmond 2013). Others provided evidence that peacebuilding can also be a product of military victory and/or illiberal practices (Lewis, Heathershaw, and Megoran 2018). But neither defines what peace means or what the essential, core elements of peace should be.

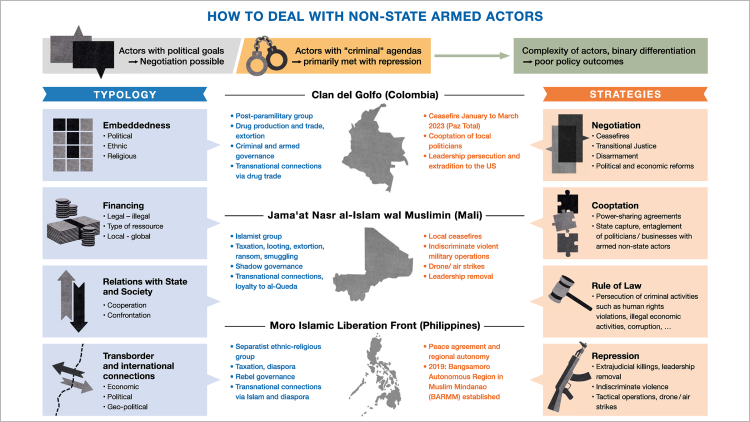

Taking the perspective that peace is more than the absence of war, three elements stand at the core of peacebuilding: the reduction of violence in all its different forms; democratic participation beyond elections; and institutions capable of transforming conflict in a non-violent and constructive way under the rule of law. The focus on stabilisation on the part of many international actors is understandable but often counterproductive, as it tends to reproduce the conflicts that escalated violently and/or to favour the actors with more military power. Peacebuilding is part of contentious politics. A peace accord may provide a roadmap or a minimal consensus on reforms, but its implementation will probably reproduce old conflicts and produce new ones as there are real or perceived winners and losers. Therefore, a focus on violence containment and prevention (beyond the relapse into war) is necessary. The experience of Latin American post-war countries shows very clearly that violence shifts towards forms not considered political. However, many of the perpetrators of violence are the same – repressive state security forces on one side, young, marginalised youth lacking prospects on the other, with criminal organisations often cooperating closely with the state and traditional elites.

Military interventions might be able to end wars but tend to fail in the middle or long term. Afghanistan demonstrates that even war termination might not be viable when armed actors are able to hold on to their power via illegal crops, sympathetic neighbouring countries, and the local population lacking stable livelihoods. A similar argument can be made for repressive security policies prioritising military responses to problems of public security. In the end these policies lead to renewed surges of violence. These strategies have high financial and political costs, as they destroy trust and reproduce grievances.

Peacebuilding Is a Permanent and Long-Term Endeavour

Peacebuilding efforts need to be context-specific. First, strategies to contain violence need to adjust to realities on the ground. Some actors might be willing to negotiate an end to violent action even if they are classified as “criminal.” El Salvador and Colombia provide evidence for a negotiated reduction of direct physical violence with the criminalised youth gangs and the paramilitaries. These pacts and negotiations have been criticised heavily for their lack of transparency, legitimacy, and accountability for grave human rights violations. This does not invalidate the violence reduction resulting from these attempts but rather advocates taking a broader approach to these negotiations (Cockayne, de Boer, and Bosetti 2016). Other actors might not be willing to lay down arms but can be isolated or marginalised by active policies of social control either by the state or by civil society. The variation of violence at the subnational and local level even in extremely violent contexts provides evidence of this. Violence is neither omnipresent nor static but changes according to conditions such as the viability of non-violent livelihoods, social cohesion, and trust in institutions as well as between persons.

Second, peacebuilding depends on the specific political context. Even in a defective democracy civil society and non-violent actors have room for non-armed action and advocacy for change. The possibilities in authoritarian and illiberal contexts differ but even here conflict transformation is necessary. Here, too, peace must go beyond the end of armed conflict. Transitions to a regime providing political participation and citizenship – that is, democracy – may take longer but might also be more sustainable if accomplished without the use of violence (Bethke and Pinckney 2021). It is the political context that structures citizenship and the access to political, social, and economic rights. Elections are important but by themselves may not lead to sustainable conflict transformation, as Central American experiences show.

Third, neither peacebuilding nor democratisation is sustainable without a peace dividend and a solid social foundation. Across the globe, the COVID-19 pandemic brought to the fore the structural inequalities between and within countries. At the end of 2021 the International Crisis Group concluded: “The economic hurt COVID-19 is unleashing could strain some countries to a breaking point. Although it’s a leap from discontent to protest, from protest to crisis, and from crisis to conflict, the pandemic’s worst symptoms may yet lie ahead” (International Crisis Group 2021). Taking these complexities of peacebuilding seriously means that social inclusion must stand at the core of policies for violence prevention and democratic participation. Otherwise, political polarisation will likely lead to further severe democratic backsliding and renewed cycles of violence in Latin America and elsewhere.

Fußnoten

References

Bethke, Felix S, and Jonathan Pinckney (2021), Non-Violent Resistance and the Quality of Democracy, in: Conflict Management and Peace Science, 38, 5, 503–523.

Birke Daniels, Kristina, and Sabine Kurtenbach (eds) (2021), Entanglements of Peace. Reflections on the Long Road of Transformation in Colombia, Bogotá, Washington: FESCOL.

Cockayne, James, John de Boer, and Louise Bosetti (2017), Going Straight. Criminal Spoilers, Gang Truces and Negotiated Transitions to Lawful Order, New York: United Nations University Centre for Policy Research, Crime-Conflict-Nexus Series No. 5, accessed 13 January 2022.

Coppege, Michel, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, and Staffan I. Lindberg (2021), “V-Dem Codebook V11” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project, V-Dem Institute, University of Gothenburg.

ERCA (2021), Estado de la Región, Informe Estado de la Región, 6, San José, Costa Rica: Estado de la Región Centroamericana, accessed 13 January 2022.

INDEPAZ (2021), Informe de Masacres En Colombia Durante El 2020 y 2021, Bogotá: Instituto de estudios para el desarrollo y la paz, accessed 13 January 2022.

International Crisis Group (2021), 10 Conflicts to Watch in 2022, 29 December, accessed 13 January 2022.

JEP (2021), Sistema Integral Solicita a La Defensoría Del Pueblo Adoptar Una Resolución Defensorial Que Trace Hoja de Ruta Para Poner Fin al Asesinato de Líderes Sociales y Excombatientes de Las Farc-EP, Comunicado 046, Bogotá: Jurisdicción Especial para la Paz, accessed 13 January 2022.

Latinobarómetro (2021), Informe Latinobarómetro 2021, accessed 29 December 2021.

Lewis, David, John Heathershaw, and Nick Megoran (2018), Illiberal Peace? Authoritarian Modes of Conflict Management, in: Cooperation and Conflict, 53, 4, 486–506.

Mac Ginty, Roger, and Oliver P Richmond (2013), The Local Turn in Peace Building: A Critical Agenda for Peace, in: Third World Quarterly, 34, 5, 763–783.

United Nations (2021), Sixtieth Report of the High Representative for Implementation of the Peace Agreement on Bosnia and Herzegovina to the Secretary-General of the United Nations, accessed 13 January 2022.

United Nations (2015), The Challenge of Sustaining Peace: Report of the Advisory Group of Experts for the 2015 Review of the UN Peacebuilding Architecture, accessed 13 January 2022.

United Nations (1987), Procedures for the Establishment of a Firm and Lasting Peace in Central America, UN A/42/521 S/19085, accessed 13 January 2022.

World Bank (2021), LAC Equity Lab: A Platform for Poverty and Inequality Analysis, accessed 29 December 2021.

Gesamtredaktion GIGA Focus

Redaktion GIGA Focus Lateinamerika

Lektorat GIGA Focus Lateinamerika

Forschungsprojekt

Regionalinstitute

Forschungsschwerpunkte

Wie man diesen Artikel zitiert

Kurtenbach, Sabine (2022), From Ending War to Building Peace – Lessons from Latin America, GIGA Focus Lateinamerika, 1, Hamburg: German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), https://doi.org/10.57671/gfla-22012

Impressum

Der GIGA Focus ist eine Open-Access-Publikation. Sie kann kostenfrei im Internet gelesen und heruntergeladen werden unter www.giga-hamburg.de/de/publikationen/giga-focus und darf gemäß den Bedingungen der Creative-Commons-Lizenz Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 frei vervielfältigt, verbreitet und öffentlich zugänglich gemacht werden. Dies umfasst insbesondere: korrekte Angabe der Erstveröffentlichung als GIGA Focus, keine Bearbeitung oder Kürzung.

Das German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) – Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien in Hamburg gibt Focus-Reihen zu Afrika, Asien, Lateinamerika, Nahost und zu globalen Fragen heraus. Der GIGA Focus wird vom GIGA redaktionell gestaltet. Die vertretenen Auffassungen stellen die der Autorinnen und Autoren und nicht unbedingt die des Instituts dar. Die Verfassenden sind für den Inhalt ihrer Beiträge verantwortlich. Irrtümer und Auslassungen bleiben vorbehalten. Das GIGA und die Autorinnen und Autoren haften nicht für Richtigkeit und Vollständigkeit oder für Konsequenzen, die sich aus der Nutzung der bereitgestellten Informationen ergeben.