- Startseite

- Publikationen

- GIGA Focus

- “Brazil must be back!” – But Real Climate Action Is Possible Only after Bolsonaro

GIGA Focus Lateinamerika

"Brasilien muss wieder da sein!" – Aber effektiver Klimaschutz ist erst nach Bolsonaro möglich

Nummer 6 | 2021 | ISSN: 1862-3573

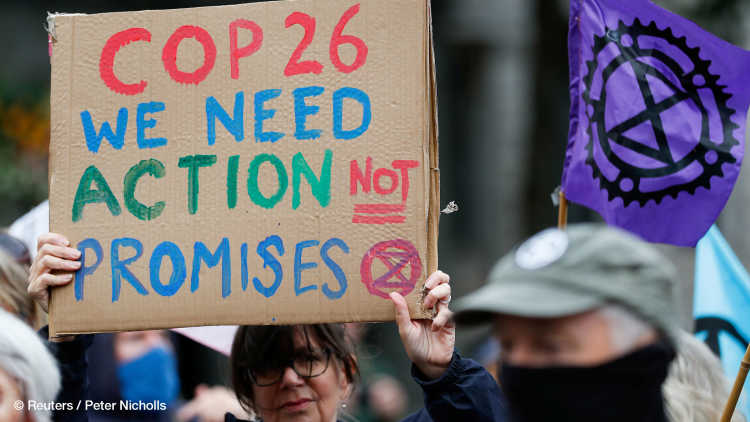

Jair Bolsonaros Präsidentschaft zeichnet sich durch eine starke Zunahme von Entwaldung und Treibhausgasemissionen, ihre Unterstützung der brasilianischen Agrarindustrie und die Unterdrückung von Indigenen sowie Umweltaktivistinnen und -aktivisten aus. Daher erstaunte es zunächst, dass sich die brasilianische Regierung auf der Klimakonferenz COP26 in Glasgow im November dieses Jahres ungewohnt kompromissbereit präsentierte und mit neuen Klimaschutzzusagen aufwartete. Dahinter steht allerdings kein Umdenken, sondern vielmehr eine Inwertsetzungsstrategie, die wirtschaftlichen Interessen dienen soll.

Brasiliens Beitrag zum internationalen Klimaschutz ist dringend erforderlich. Aufgrund des Rückbaus von Klimaschutzmaßnahmen und dem starken Anstieg von Entwaldung und Treibhausgasemissionen unter der Regierung Bolsonaros, wirken die jüngsten Klimaschutzversprechen der Regierung zunächst durchaus überraschend.

Ein genauerer Blick auf die Bilanz der Regierung und ihre neuen Versprechen zeigt jedoch, dass sie keine wirkliche Wende in der Klimapolitik des Landes darstellen. Neben der üblichen „Greenwashing-Rhetorik“, die das Image des Landes verbessern soll, sind sie vorrangig als Versuch zu verstehen, Profite aus Klimaschutzmechanismen, wie beispielsweise internationalem Emissionshandel, zu sichern.

Eine Wende hin zu einem größeren und ernstzunehmenden Engagement Brasiliens im Klimaschutz auf nationaler und internationaler Ebene wird erst nach den kommenden Präsidentschaftswahlen im Oktober 2022 möglich sein. Bis dahin sind die Hoffnungsträger für effektiven Klimaschutz und Klimagerechtigkeit vor allem Lokalregierungen und zivilgesellschaftliche Initiativen. Beide haben auf der Konferenz in Glasgow große Einigkeit und Entschlossenheit demonstriert.

Fazit

Bis zur wahrscheinlichen Wahl einer neuen Regierung im Jahr 2022 sollten europäische Politikerinnen und Politiker und Nichtregierungsorganisationen aktiv indigene Gemeinschaften sowie subnationale und zivilgesellschaftliche Initiativen unterstützen, die sich für nachhaltigen und sozial gerechten Klimaschutz einsetzen. Europäische Banken und Unternehmen sollten Investitionen in „Greenwashing-Initiativen“ vermeiden und stattdessen nachhaltige und sozial verantwortliche Klimaschutzinitiativen unterstützen.

Brazil in Glasgow – Two Tales of a Country

The little room at COP26, the United Nations Climate Change Conference held in November 2021 in Glasgow, was packed with people. Despite the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and concomitant recommendations to keep distance, civil society activists, researchers, political representatives, and members of the media squeezed themselves into one of the small pavilions to attend a discussion with indigenous and quilombola (“maroons”: residents of quilombolo settlements, originally established by escaped slaves) activists from the Amazon region. Three female indigenous leaders and environmentalists – Juma Xipaia, Alessandra Korap, and Sandra Braga – talked about their struggles against the Belo Monte hydropower plant and new dam construction projects in the Amazon and how much these interventions altered nature and community life, affirming that they had no intention of giving up the Amazon rainforest. “The forest is only standing because we protected it with our own lives,” said Juma, arguing that everyone should care about the Amazon and the indigenous communities who are protecting it, as it has an importance for the entire world. These remarks, along with the “Away with Bolsonaro” statement at the end of the event, met with thunderous applause.

Obviously, this event did not take place in Brazil’s official COP pavilion, but at the so-called Brazil Climate Action Hub. In the latter, Brazil’s civil society, scientists, and local politicians came together to show the world that there is a different Brazil than that of the climate-sceptic president, Jair Bolsonaro. The unofficial counter-pavilion evoked memories of the “We Are Still In” coalition at COP23 in Bonn in 2017, where US local governments demonstrated their motivation to continue climate action despite their federal government’s decision to leave the Paris Agreement. Yet, in contrast to Donald Trump’s open rejection of any climate protection measures, the Bolsonaro government has made an effort in 2021 to present Brazil as a climate pioneer. Brazil’s official pavilion celebrated a success story with events such as “Brasil: País da energia limpa!” (Brazil: Country of clean energy!) or “Brasil: O país em que a eficiência energética já é realidade no setor elétrico” (Brazil: The country where energy efficiency is already a reality in the electricity sector). Moreover, it promoted Brazil’s potential for voluntary carbon markets, its big hydropower dams, investment opportunities in hydrogen, and the latest green growth initiative of the government.

Bolsonaro himself, who has been Brazil’s president for nearly three years now, did not attend the COP26 summit. Instead of heading to Glasgow, he extended his stay in Italy following the G20 meeting in Rome. He shares his absence with other right-wing populist and (semi-)autocratic presidents, such as Vladimir Putin and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. Yet, Brazil was far from absent from this climate summit. Several pre-COP announcements, along with the country’s performance at the event, suggest that the government is trying to refurbish its international image. At first, several new pledges to undertake actions such as reducing emissions, halting deforestation, and reaching carbon neutrality might appear surprising – or perhaps even absurd – given the government’s record of disastrous environmental and climate policies, which have led to rising emissions and an exorbitant increase in deforestation in recent years. Indeed, they do not indicate a changed mindset and increased openness towards climate action: instead, they must be understood as a strategy to improve Brazil’s image and secure profits from climate protection mechanisms.

Bolsonaro’s Record: Reverse Momentum for Climate Protection and Environmental Justice

While it has been in power for only about three years, the Bolsonaro presidency has effectuated major regressions in several policy fields, if ecologically sustainable and socially equitable development are seen as yardsticks. His administration has shepherded an increase in severe human rights violations, restrictions on scientific freedom and freedom of the press, and the persecution and oppression of indigenous peoples and civil society activists. Brazilian senators recently voted in favour of criminally charging Bolsonaro for the government’s downplaying and mismanagement of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has so far led to more than 600,000 deaths in the country, the second-highest death toll worldwide after the United States. They recommend that the case be submitted to the International Criminal Court (ICC), where Bolsonaro should stand in judgment for crimes against humanity.

The government’s record on climate and environmental protection is equally devastating. The Bolsonaro administration has publicly expressed its opposition to many of the existing policies in these fields and has passed regulations and legislation that weaken environmental protection, civil society participation, and policy oversight. It has expanded the influence of Brazilian agribusiness and paved the way for an increasing exploitation of the Amazon, massive deforestation, and the curtailing of indigenous rights. This has led to another accusation of crimes against humanity against Bolsonaro: supported by Brazilian civil society organisations, the Austrian environmental justice campaigner Allrise submitted a case to the ICC in mid-October 2021 arguing Bolsonaro should be responsible for crimes against environmental dependents and defenders related to the destruction of the Amazon (Allrise 2021).

Bolsonaro has openly demonstrated his contempt for any form of climate and environmental protection from the very beginning. Following his partner in crime, Donald Trump, he promised a withdrawal from the Paris Agreement (a plan from which he ultimately stepped back) and revoked the Brazilian candidature to host COP25 in 2019. Fake news propaganda to discredit the opposition was spread by former foreign minister Ernesto Araújo (January 2019 – March 2021). Araújo called climate change a conspiracy theory among cultural Marxists, who were supposedly working to expand Western and Chinese influence over Brazil. This bizarre narrative fits perfectly with the thesis that climate protection measures are an instrument of foreign powers to control the Amazon and appropriate its resources. The Amazon being threatened by foreign takeover is a recurring narrative that was also prevalent under the military regime (Viola and Franchini 2018). Bolsonaro even insinuated that NGOs have caused forest fires in pursuit of this undertaking.

The government’s anti-climate agenda has not stopped at rhetoric. Over the last years, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions have been rapidly growing. Even in 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic led to falling emissions in most parts of the world, emissions in Brazil increased by 9.5 per cent. Currently, the country is the sixth-largest GHG emitter globally. Land use, land use change, and forestry – together referred to as “LULUCF” in climate change debates – have been the most significant drivers of Brazil’s emissions since 1990, with deforestation being the largest and agriculture the second-largest source of GHG emissions. The emissions increase is a direct result of Bolsonaro’s forestry and agriculture policy, agribusiness its main driver.

The fight against deforestation has experienced significant setbacks under the Bolsonaro administration. Thanks to successful enforcement of anti-deforestation policies that, between 2004 and 2012, significantly slowed agricultural expansion, both emissions and deforestation rates in the Amazon decreased enormously in this time period, the latter by 84 per cent (Nepstad et al. 2014; Silva Junior et al. 2021). While deforestation had already started to increase again in 2013, the situation has severely worsened since Bolsonaro took office. In 2019 the rate of deforestation was 34 per cent higher than in 2018, and 120 per cent higher than the historic low in 2012 (Climate Action Tracker 2021; Silva Junior et al. 2021).

This rapid increase in deforestation is a direct outcome of Bolsonaro’s policies. Illegal deforestation is a result of the government’s dismantling and systematic underfunding of forest protection institutions. While he did not completely abolish the Ministry of the Environment (Ministério do Meio Ambiente, MMA) or merge it with the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, and Food Supply (Ministério da Agricultura, Pecuária e Abastecimento, MAPA) as he initially intended, Bolsonaro significantly reduced its tasks and cut its funding. For example, public forest management, including oversight of forest concessions, was transferred to the MAPA, and the climate change secretariat and the environmental education department were completely abolished.

The leadership of important environmental oversight institutions linked to the MMA was handed over to military police officers. This includes the Brazilian Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (Instituto Brasileiro do Meio Ambiente e dos Recursos Naturais Renováveis, IBAMA), the Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation (Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade, ICMBio), and the National Institute for Space Research (Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais, INPE). All three institutions entrusted with the oversight and protection of the environment and the fight against environmental crime have been systematically disempowered. A presidential decree in May 2020 subordinated IBAMA and ICMBio to the Brazilian Armed Forces, which practically means that the defence minister can oversee and decide upon possible missions (Russau 2020). Additionally, in early 2021, a new oversight rule was established that allows ICMBio’s new military directors to review all “manuscripts, texts and scientific compilations” before they can be published, allowing for political censorship (Escobar 2021).

Brazilian agribusiness is a key driver of deforestation. According to the Climate Observatory, a Brazilian NGO and think tank network, combining emissions from agriculture (27 per cent) and deforestation (46 per cent) indicates that Brazilian agribusiness is responsible for nearly three quarters of the country’s total emissions (Observatório do Clima 2021).

One important step in Bolsonaro’s systematic strengthening of Brazil’s agribusiness was the widening of the competencies of the MAPA. As one of his first moves in office, in January 2019 the president issued an executive order that made the MAPA responsible for deciding on indigenous people’s land claims, which was formerly a competency of the indigenous affairs agency known as FUNAI (Fundação Nacional do Índio). The same order also placed the Brazilian Forestry Service – which was formerly under the purview of the Ministry of the Environment and usually promoted a more sustainable use of forests – under the Ministry of Agriculture and made it responsible for the management of public forests. This step has been understood as a clear sign that Bolsonaro is working towards a greater commercial exploitation of the Amazon (Stargardter and Boadle 2019) – precisely what Juma, Alessandra, and Sandra, and likeminded people have been fighting against for years.

Seeking Benefits from Increased Commodification of Climate Protection

Contrary to its anti–climate protection rhetoric, the denigration of environmental activists and indigenous peoples, and the devastating ecological consequences of its agro-industrial policies, the Bolsonaro government appeared to have become more engaged in climate action in the second half of 2021 – at least at first sight. Major topics of COP26 were carbon markets, forest protection and halting deforestation, the role of forests as carbon sinks, net-zero pledges, and nature-based solutions (largely replacing the REDD+ mechanism). The Brazilian government demonstrated a much more moderate position in the negotiations and promoted the establishment of carbon markets, nature-based solutions, and green growth in general. Clearly, the Bolsonaro government has been keen to present Brazil in a “green” light to encourage investment and financing.

Shortly before COP26, the Brazilian government launched two new climate initiatives, a green growth programme and a new version of an already existing low-carbon agriculture programme. Additionally, it announced increased emission reduction targets that foresee a reduction of 50 per cent by 2030, oriented around baseline year 2005. By 2050, it claims, net-zero emissions shall be achieved (instead of by 2060, which was the previous goal). While in the past Brazil used to emphasise that its targets are conditional – meaning, dependent on external funding – they have since been declared unconditional. Moreover, Brazil signalled that it will be more flexible concerning the disagreements on Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, specifically the issue of carbon trading-related mechanisms. During this year’s COP, the Brazilian delegation indicated its heightened willingness to participate in multilateral agreements. For example, together with more than 100 other countries, it became a signatory to the Glasgow Declaration, initiated by the UK COP presidency, which aims to stop deforestation by 2030.

The new climate approach of the Brazilian government was seen to be linked to a change in personnel, specifically a new environmental minister and a new foreign minister. In March 2021 former foreign minister Ernesto Araújo was replaced by Carlos Alberto França, who announced a general interest in reintegrating Brazil into multilateral organisations, staying in the Paris Agreement, and combatting deforestation. Additionally, former environmental minister Ricardo Salles stepped down in June 2021 after being the subject of two police investigations related to illegal deforestation in the Amazon and being accused of smuggling timber into the United States. Consequently, COP26 was headed by his successor, Joaquim Leite, whose approach has been optimistically called “ambientalismo de resultado” – environmentalism that delivers.

However, the apparent change of course under Leite must be seen as a mere change of strategy. Leite formerly served as director of the Forest Conservation and Environmental Services Department and secretary for the Amazon and Environmental Services in the same ministry, which makes him co-responsible for the vast deforestation increase in recent years. Just like his former boss, he belongs to the “ruralistas” (large landowners and their representatives), having served for 23 years as a board member of the Sociedade Rural Brasileira (Brazilian Rural Society), an organisation representing Brazilian agroindustry. It is therefore not surprising that agribusiness, which is one of the major drivers of deforestation, continues to have significant influence in the Ministry of Environment.

Brazilian private business, specifically agribusiness, also exerted a strong influence on the government in this year’s COP negotiations. This sector has demonstrated particular interest in carbon markets – which were a major theme in Glasgow and extensively promoted by the Brazilian government there. Brazil’s official pavilion at COP26 was sponsored by industry and agribusiness associations. This is not a feature unique to Brazilian official representation: Several country pavilions and the COP as a whole were sponsored by large companies, and lobbying has been widespread at all COP events. Corporate Accountability, Corporate Europe Observatory, and other NGOs pointed out that with 503 persons, fossil fuel lobbyists (according to the official list of participants) outnumbered the biggest country delegations. In the case of Brazil, some of them were part of the official delegation.

In part due to pressure from the Brazilian business sector, the Bolsonaro government is now seeking a more moderate approach to climate negotiations and has shifted its focus to targeting the economic benefits that climate instruments might bring. Prior to the COP negotiations, several Brazilian business executives urged the government to resolve the Article 6 debate and support the establishment of a global carbon-offsets market. Article 6 has been one of the most contested issues since Paris 2015 and was meant to be resolved in Glasgow. The passage regulates the cooperation mechanisms for implementing climate protection goals. A central mechanism is a global carbon market, which allows for the offsetting of emissions through a trade and credit system that allows for a transferral of emission reductions between countries. Industrialised countries and companies can thereby achieve emission reductions or even the often announced “net-zero” goal through compensations in other countries.

Forests play a crucial role in these kinds of deals as they function as global carbon sinks. With the Amazon, Brazil has one of the biggest carbon sinks worldwide. This means that Brazil could provide a large number of credits for carbon offsetting. However, at the 2019 negotiations in Madrid, the Brazilian delegation was still blocking common carbon market rules. The dispute about Article 6 was mainly about two issues: Brazil wanted the carbon credits that had been generated according to the 1997 Kyoto Protocol to be incorporated into a new carbon market under the Paris Agreement, as it holds many of these credits. Others have questioned whether these credits fulfil the standards required by the Paris Agreement. Moreover, in Madrid, Brazil still insisted on the possibility of double-counting the credits, meaning that it refused to discount credits sold in the past from its mitigation results. Similarly, there was a debate about how to deal with credits that are sold by businesses in one country to companies or governments of another country. In the past, Brazil refused to exclude these offsets from its own mitigation targets. However, in Glasgow, Brazil announced its willingness to accept the adjustments if some Kyoto credits would be included in the new system.

As for the climate programmes and emissions reduction targets initiated shortly before the COP, upon closer examination they are less convincing. Climate Action Tracker (CAT) rates Brazil’s targets “highly insufficient.” In December 2020 Brazil submitted an updated Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) – efforts by each country to reduce national emissions and adapt to the impacts of climate change – where instead of improving targets, it merely confirmed previous ones for 2025 (37 per cent emissions reduction) and 2030 (43 per cent emissions reduction). For both targets the baseline year is still 2005, which was a year with particularly high emissions. Thus, the targets represent rather unambitious goals. In fact, the pledge is not only a confirmation but rather a weakening, as the emissions calculation for the baseline year has been updated. According to CAT, this raises the 2005 emissions significantly, which is why the targets were, in fact, lowered. This means that Brazil could continue to increase its emissions and still officially meet its targets (Climate Action Tracker 2021). Brazil’s latest pledge to reduce 50 per cent of its greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 is related to the same base-year calculation and, thus, is far less progressive than it seems.

Several recently proposed bills that might aggravate emissions are currently underway in the legislature or have been introduced as new regulations. This includes changes to environmental licensing regulations, indigenous land titling, and land grabbing on public lands. Bill 490, proposed in June 2021, foresees the economic exploitation of indigenous land. It might also make land titling for indigenous people even more difficult than it already is. Even before the Glasgow COP, Brazil had launched several initiatives aiming to establish market-friendly climate policies, at the expense of indigenous and quilombola communities and long-term, sustainable climate and forest protection. This includes the 2021 “adopt a park” programme that allows big multinational companies to “adopt” a conservation area, which includes even those on quilombola territory.

A more positive example of ongoing climate-related policy initiatives can be found in the energy sector. A recent bill on solar energy enjoys broad support across party lines and was recently passed by the Brazilian Chamber of Deputies. The bill, which supports small-scale solar energy generation and is thereby likely to increase energy access, including in poorer regions, is currently awaiting approval from the Federal Senate. However, at the same time, the Brazilian government has been attempting to sell the high share of hydropower in its electricity mix as a success story, despite obvious problems in supply, an increase in fossil fuels, and the negative environmental and socio-economic consequences. While emissions from the Brazilian energy sector are lower compared to those of other countries, they are still increasing steadily. Moreover, using the energy sector to present Brazil as a low-carbon economy is misleading due to the high emission rates from land use and deforestation.

Although the promises made by the Brazilian government at the last climate summit may seem surprising at first, they do not represent a real shift in the country’s climate policy. Instead, the latest pledges need to be understood as an attempt to greenwash Brazil’s image and secure profits from financialised conservation mechanisms such as voluntary carbon markets. The announced policies, such as the green growth programme, which still lacks clear targets and implementation pathways, appear to be in line with the increasing privatisation and commodification of climate protection in general.

Local Climate Action Is Key – At Least until the 2022 Election

It is to be expected that Brazil will now open up more to certain climate initiatives – provided these appear financially attractive. This includes emissions trading, nature-based solutions, and other green capitalism instruments that currently enjoy priority in international climate protection. However, these initiatives are not expected to sufficiently halt the deforestation and degradation of the Amazon or other important protected ecosystems such as the Atlantic Forest or the Cerrado Savannah. Moreover, the repression and displacement of the indigenous population and the quilombolas, who play an important role in the conservation and protection of the forests, will continue under the current government. Driven by the interests of the agroindustry, the Bolsonaro government took several steps in 2021 to further curtail the rights of indigenous communities and undermine forest protection.

The COVID-19 pandemic has further weakened the environmental regulations and agencies Bolsonaro had already begun to disempower. Environmental enforcement agents have been asked to self-isolate at home, and legislators have attempted to use the fast-track legislation process that was put in place for COVID-19 measures to approve highly controversial ownership rights for illegally deforested land. New regulatory initiatives might worsen the situation for indigenous peoples and lead to weaker environmental licensing.

Nevertheless, there are a number of smaller initiatives that inspire hope. Many subnational governments have launched their own climate policies independently of the central government. Civil society organisations and representatives of indigenous and quilombola communities, as well as agricultural cooperatives, continue to fight to ensure that climate protection in Brazil is not just a new marketing tool or an instrument to improve the image of government and agribusiness.

The Glasgow conference showed the strong network these actors have been building. As in the event with Juma, Alessandra, and Sandra, the atmosphere among Brazilian civil society and representatives of subnational governments was combative, but also hopeful. In a larger closing event towards the end of the first week where many of the participants presented their visions for Brazil, they shared the perspective that they were preparing to rebuild the country after Bolsonaro’s term. Current polls make a Bolsonaro re-election in October 2022 look unlikely. As former environmental minister Isabella Teixeira said in one of the side events at COP26, “Brazil must be back!” But real climate action will require a new government.

Fußnoten

Literatur

Allrise (2021), Communication under Article 15 of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court Regarding the Commission of Crimes Against Humanity Against Environmental Dependents and Defenders in the Brazilian Legal Amazon from January 2019 to Present, Perpetrated by Brazilian President Jair Messias Bolsonaro and Principal Actors of his Former or Current Administration, submitted in The Hague on 12 October.

Climate Action Tracker (2021), Brazil, https://climateactiontracker.org/countries/brazil/targets/ (29 November 2021).

Escobar, Herton (2021), ‘A Hostile Environment.’ Brazilian Scientists Face Rising Attacks from Bolsonaro’s Regime, Science, 7 April, www.sciencemag.org/news/2021/04/hostile-environment-brazilian-scientists-face-rising-attacks-bolsonaro-s-regime (8 December 2021).

Nepstad, Daniel et al. (2014), Slowing Amazon Deforestation Through Public Policy and Interventions in Beef and Soy Supply Chains in: Science, 344, 6188, 1118–1123, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1248525.

Observatório do Clima (2021), Against Global Trend, Brazil Increased Emissions During The Pandemic: Press Release, 28 October, www.oc.eco.br/en/na-con tramao-do-mundo-brasil-aumentou-emissoes-em-plena-pandemia/ (8 December 2021).

Russau, Christian (2020), Präsidialdekret: Militarisierung der Umweltüberwachung in Amazonien schreitet voran, 9 May, www.kooperation-brasilien.org/de/themen/landkonflikte-umwelt/praesidialdekret-militarisierung-der-umwelt ueberwachung-in-amazonien-schreitet-voran (8 December 2021).

Silva Junior, Celso H. L.et al. (2021), The Brazilian Amazon Deforestation Rate in 2020 is the Greatest of the Decade, in: Nature Ecology & Evolution, 5, 2, 144–145.

Stargardter, Gabriel, and Anthony Boadle (2019), Brazil Farm Lobby Wins as Bolsonaro Grabs Control over Indigenous Lands, in: Reuters, 2 January, www.reuters.com/article/us-brazil-politics-agriculture-idUSKCN1OW0OS (8 December 2021).

Viola, Eduardo, and Matías Franchini (2018), Brazil and Climate Change Beyond the Amazon, Routledge: Abingdon, New York, NY.

Gesamtredaktion GIGA Focus

Redaktion GIGA Focus Lateinamerika

Lektorat GIGA Focus Lateinamerika

Regionalinstitute

Forschungsschwerpunkte

Wie man diesen Artikel zitiert

Fünfgeld, Anna (2021), "Brasilien muss wieder da sein!" – Aber effektiver Klimaschutz ist erst nach Bolsonaro möglich, GIGA Focus Lateinamerika, 6, Hamburg: German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-76295-4

Impressum

Der GIGA Focus ist eine Open-Access-Publikation. Sie kann kostenfrei im Internet gelesen und heruntergeladen werden unter www.giga-hamburg.de/de/publikationen/giga-focus und darf gemäß den Bedingungen der Creative-Commons-Lizenz Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 frei vervielfältigt, verbreitet und öffentlich zugänglich gemacht werden. Dies umfasst insbesondere: korrekte Angabe der Erstveröffentlichung als GIGA Focus, keine Bearbeitung oder Kürzung.

Das German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) – Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien in Hamburg gibt Focus-Reihen zu Afrika, Asien, Lateinamerika, Nahost und zu globalen Fragen heraus. Der GIGA Focus wird vom GIGA redaktionell gestaltet. Die vertretenen Auffassungen stellen die der Autorinnen und Autoren und nicht unbedingt die des Instituts dar. Die Verfassenden sind für den Inhalt ihrer Beiträge verantwortlich. Irrtümer und Auslassungen bleiben vorbehalten. Das GIGA und die Autorinnen und Autoren haften nicht für Richtigkeit und Vollständigkeit oder für Konsequenzen, die sich aus der Nutzung der bereitgestellten Informationen ergeben.