- Home

- Publications

- GIGA Focus

- Latin America’s Fight against Corruption: The End of Impunity

GIGA Focus Latin America

Latin America’s Fight against Corruption: The End of Impunity

Number 3 | 2017 | ISSN: 1862-3573

Since the adoption of the Anti-Corruption Action Plan in 2010, the G20 has tried to promote market integrity and a clean business environment. Under the German G20 presidency, a working group co-chaired by Germany and Brazil has been seeking to advance this agenda. Since the so-called Odebrecht scandal – a large-scale corruption scheme that entangled most Latin American countries – the relevance of the topic has become widely recognised.

Latin America was a frontrunner in intergovernmental anti-corruption treaties. Nevertheless, corruption is still deeply engrained and widespread in Latin America. Governments from various ideological backgrounds are currently under scrutiny due to corruption charges.

Corruption in Latin America has not increased in recent years, but the exposure and social disapprobation of corruption has. In many Latin American countries democratisation has failed to cope with organised crime and social marginalisation �– both of which are important drivers of violence and corruption.

The exceptional cases of Chile, Uruguay, and Costa Rica provide evidence of the key role elites, state institutions, and democratic accountability play in coping with these problems.

Direct consequences of anti-corruption campaigns and scandals may be ambivalent as they delegitimise institutions and the political system. This might open the floor to outsiders and populists, resulting in deeper institutional crises.

Policy Implications

While international initiatives against corruption such as the G20 Anti-Corruption Agenda can serve as important reference points, strengthening the independence of judicial systems and civil society organisations in monitoring corruption and enforcing existing laws should be a priority. The subordination of economic and political elites to the rule of law is a must for anti-corruption policies as well as for sustainable development.

The Changing Contexts of Corruption

Corruption is a major issue in international, regional, and national debates. The Organisation of American States (OAS) was the first to adopt an anti-corruption convention in 1996. It was followed by other regional and international organisations – notably, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in 1997 and the United Nations (UN) in 2003. The G20 established an anti-corruption working group in its first meeting at the 2010 summit in Toronto. The current working group is co-chaired by Germany and Brazil – ranked 10th and 79th, respectively, in Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index. The rationale behind the G20 anti-corruption agenda is that “corruption threatens the integrity of markets, undermines fair competition, distorts resource allocation, destroys public trust, and undermines the rule of law. Corruption is a severe impediment to economic growth, and a significant challenge for developed, emerging and developing countries.” Anti-corruption mechanisms such as the OAS and the UN use a broader approach and link corruption explicitly to the legitimacy of public institutions. In this respect, the anti-corruption treaties of these organisations can contribute to enhancing the legitimisation of both national and international governance (Narlikar 2017).

Even though corruption standards, corruption legislation, and people’s perception of corruption change, there is an emerging consensus on the negative impact of corruption on economic development and democratic accountability. Both aspects are closely interrelated, and – due to persistent social inequality and asymmetric political power relations – the latter is at the core of the current corruption scandals in Brazil and other Latin American countries. These states are breeding grounds for old and new patterns of populism, clientelism, and patrimonialism. The lines between these phenomena and corruption are blurred. Anti-corruption mechanisms focus on the illicit appropriation of public resources for private gain, but twisting existing legislation for private or political gain is a closely related phenomenon. The most widespread related practices consist of:

influencing political processes such as elections through campaign contributions (either to political parties or specific candidates) or by using state funds to give preferential treatment to specific electoral constituencies

paying bribes to those employed by state institutions (police, judiciary) in order to circumvent legal rules

paying bribes in order to get access to public contracts such as infrastructure projects.

Despite its long tradition in Latin America, corruption has only been a prominent topic since the region’s political regimes began to democratise in the 1980s. Thus the series of infamous corruption cases that swept the region in the 1990s do not necessarily indicate that corruption increased during that time frame but could rather reflect increasing public awareness and controls in democratic political regimes (Casas-Zamora and Carter 2017; Weyland 1998). The spread of national chapters of Transparency International and the adoption of the Inter-American Convention against Corruption was a result of this growing awareness in Latin American societies. Unfortunately, the region remains a place where the rules are not enforced (Franco and Scartascini 2014). Why should one expect a different outcome in regard to anti-corruption laws?

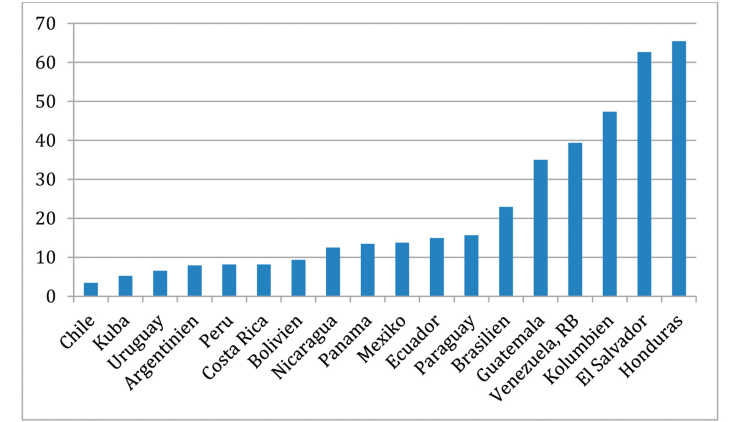

Corruption and high levels of violence are still major problems across Latin America – though there are significant regional variations (see figures 1 and 2).

It is interesting that variations along both topics single out the same group of countries: Costa Rica, Chile, Uruguay, and Cuba. These four states have low levels of homicide and high levels of corruption control. Costa Rica, Chile, and Uruguay perform well on a wide range of governance indicators and score high as democratic regimes. Cuba’s positive performance might be down to a lack of independent data or an authoritarian regime’s successful control of corruption and violence. But the vast majority of Latin American countries still face serious problems. How can we explain this?

Democratisation has failed to deal with two important drivers of corruption and violence: (a) organised crime, particularly the drugs trade, and (b) high levels of inequality (e.g. income inequality and inequality in access to state and public policies). Furthermore, there is a lack or complete absence of effective policies in the fields of prevention, rule of law, and social inclusion; although their influence is rather indirect, they are also important.

Various combinations of factors shape the degree of corruption and violence as well as society’s response to these phenomena. Institutional capacity and an independent judiciary are key for non-violent conflict transformation and the enforcement of the rule of law, whereas civil society and independent media are important for demanding accountability and transparency. Meanwhile, social inclusion policies are a major mechanism of prevention. All these factors are also relevant for trust in public institutions and their levels of legitimacy.

A government’s economic performance is crucial to the levels of mobilisation and protest a country experiences. These levels are higher in times of recession and lower during phases of economic growth (Casas-Zamora and Carter 2017). The recent corruption scandals in Guatemala and Brazil reveal the complex interplay of different factors.

Guatemala – Impunity Past and Present

Corruption in Guatemala stems from high levels of impunity which are closely related to the gross human rights violations that occurred during the civil war, when the indigenous population was the main target of state repression (CEH 1999). After the war ended in 1996, Guatemalan political, economic, and military elites opted to maintain the repressive and exclusionary status quo instead of strengthening state institutions such as the judiciary. Impunity is not limited to wartime crimes but persists. After Philip Alston – the UN Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary, or arbitrary killings – visited the country in 2006, he stated that “Guatemala is a good place to commit murder because you will almost certainly get away with it” (United Nations General Assembly 2007: 20). In the following years international pressure to combat organised crime and impunity increased. In 2007 the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG) was established with the mandate to support the Attorney General’s office. The CICIG played a key role in uncovering the influences of criminal organisations on elections and party politics via direct and hidden campaign financing (CICIG 2015). Two dedicated general prosecutors – Claudia Paz y Paz (2010–2014), a former human rights activist, and Thelma Aldana (2014–present) – helped to strengthen and professionalise the judiciary by introducing a series of reforms and sending symbolic cases to court. The most important case was the genocide trial against Rios Montt, the former president and a former general. Montt was subsequently found guilty of genocide and crimes against humanity in May 2013, but the Constitutional Court overruled the verdict 10 days later due to political pressure.

Corruption levels reached a new high during the presidency of Otto Pérez Molina (2012–2015), a former general who was elected on a hard hand agenda against crime. The first allegations of corruption started to surface early on, but it took more than three years for protests to emerge. In 2015 a combination of economic crisis, a lack of public policies to mitigate gross social inequalities, and a severe hospital crisis led an array of actors to mobilise against government corruption. In April 2015 there were a series of corruption scandals, known as La Linea, which involved President Pérez Molina, Vice President Roxana Baldetti, and most of their ministers diverting money from the customs agency and into their private accounts at an estimated rate of over USD 300,000 per week (InSight Crime 2016).

Despite the protesters’ success in bringing down the corrupt government, it is far from evident that Guatemala has reached a tipping point. For instance, the brother (and long-time business partner) of President Jimmy Morales (2016–present), a former comedian who ran on the slogan “neither thief nor corrupt,” is currently facing corruption charges as is the president’s son. Nevertheless, public protest has calmed down – at least until the next bigger scandal erupts.

Brazil – Lava Jato and the End of Impunity

The current corruption scandal in Brazil, which will be discussed below, might be a turning point in the fight against corruption in Latin America. For the first time, top executives and high-ranking politicians were charged and convicted (and given lengthy prison sentences) by an independent judiciary and under pressure from civil society. Moreover, testimony offered in exchange for reductions in sentences made it possible for investigators to uncover the workings of a well-established, continent-wide kick-back scheme.

Operation Car Wash (Operação Lava Jato) is Brazil’s and perhaps Latin America’s biggest ever corruption investigation. It started as a money laundering enquiry[3] in 2014 but uncovered evidence of a kickback and bribery scheme in the state-run oil company Petrobras. Investigators allege that Petrobras executives were accepting bribes in return for awarding contracts to construction firms at inflated prices. The bribes were then split between Petrobras executives, middlemen, and political parties for campaign funding (particularly among those that supported the government). The investigation into this case of corruption remains open, but total pay-offs may exceed USD 5 billion (Padgett 2017).

As part of the enquiry, Brazilian investigators began to focus on construction contractors. They uncovered a cartel in the lucrative and growing Brazilian construction sector, which was sharing out contracts and rigging prices on various projects (e.g. big infrastructure projects, the FIFA World Cup, and the Olympic Games). Construtora Norberto Odebrecht S.A., the biggest engineering and contracting company in Latin America, was revealed to be at the centre of the corruption allegations, thus transforming the scandal from a Brazilian affair into a Latin American affair; in fact, there were also criminal proceedings in the United States and Switzerland.[4]

Disclosures relating to Lava Jato and Odebrecht were only made possible by using “rewarded collaboration” (colaboração premiada), which was formalised in Brazil with the Organised Crime Law of 2013 (Nicholson 2015). This tool allowed the judiciary to offer reduced sentences in exchange for detailed confessions incriminating the architects and other participants of criminal activities. While this procedure is not beyond criticism, it was the only viable strategy to identify the politicians and businesses involved in this extensive corruption network. Moreover, due to the fact that politicians in office enjoy certain judicial privileges, Brazilian investigators targeted businesspeople first and then used their confessions against politicians.

In March 2016 Marcelo Odebrecht was sentenced to 19 years in prison. Later, he and 77 other Odebrecht executives agreed to act as key witnesses for the state in exchange for reduced sentences. During court proceedings, it was revealed that the company had a secret branch to manage illegal payments (totalling USD 800 million) for securing government contracts in at least 12 Latin American countries. The bribery scheme covered the whole political spectrum, from Hugo Chávez’s Venezuela to Ricardo Martinelli’s right-wing government in Panama (El País 2017). Even the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) received payments from Odebrecht. During the last Colombian election in May 2014, the campaigns of both President Santos and his main competitor Oscar Zuluaga received funding from Odebrecht. In Peru three former presidents are under investigation. Meanwhile, in Brazil the Supreme Court authorised the investigation into over 100 leading politicians in April 2017. Furthermore, five former Brazilian presidents have been implicated as has the country’s current president, Michel Temer. Although these revelations could lead to Temer being impeached, it is worth noting that court-type evidence is not decisive in impeachment trials, which are typically political decisions that depend on political majorities (Llanos and Nolte 2016). Dilma Rousseff, for instance, was removed from office by impeachment because she had lost support in Congress; she was accused of administrative manipulations but not of corruption. The current Brazilian president will survive as long as there is no majority to depose him.

The Odebrecht scandal has the classical ingredients for corruption: companies with state participation (Petrobras), big infrastructure projects decided by public tenders, illegal party and campaign financing, and private enrichment by politicians who commit their crimes in a historical context of impunity and judicial privileges. The scandal also demonstrates that as Latin American companies internationalise their activities, both corruption and the criminal prosecution of corrupt politicians become transnational activities. In February 2017 the general attorneys of 15 countries involved in the Odebrecht investigations met in Brasilia.

The Basis of Accountability – Elites and State Institutions

Transparency International has always classified Chile, as well as Costa Rica and Uruguay, as one of the few Latin American countries with a low corruption score. Why is Chile different? There seems to be a certain path dependency going back to late colonial times and the period of early state building in Latin America. For most of its history, Chile is characterised by the probity of its political class and strong political institutions (Silva 2016). During the twentieth century, Chile had strong and non-corrupt technocratic state agencies, an independent judicial system, and efficient controlling state institutions such as the National Comptroller Agency (Controlaría General de la República), which was created in 1927. The only exception in regard to probity and corruption control was the Pinochet regime, which was characterised by the personal enrichment of the dictator, his family, and his inner circle. These corrupt practices had been concealed at the time and subsequently created tension between Pinochet, who was still commander-in-chief of the army, and the new democratic government. Under democratic rule since 1990, Chile has returned to its historic trajectory by (i) strengthening independent control mechanisms through, for example, creating the positions of an independent national prosecutor (fiscalía nacional) and a special prosecutor for safeguarding fair competition (fiscalía nacional economíca), (ii) promulgating new legislation to guarantee public probity, (iii) increasing transparency, for example, in regard to public procurements and access to government information, and (iv) regulating party financing, because illegal campaign finances and not personal enrichment have been a major issue in many corruption scandals. The recent increase in the number of cases regarding illegal campaign contributions are not evidence of growing corruption (as data about corruption victimisation demonstrate; Aninat and González 2016) but rather of more efficient prosecution and a more demanding civil society (Navia 2015). Chileans have a very low tolerance for corrupt practices within the public sector, and there seems to be a growing willingness to denounce cases of corruption (Ramírez and Vinagre 2016). At the same time, the issue of corruption formed a key part of many electoral campaigns, which resulted in a higher perception of corruption that was only partially related to a real increase in corrupt practices (Aninat and González 2016). This campaign tactic also had the unintended consequence of damaging the image of the entire political class in the eyes of the Chilean electorate (Silva 2016).

Uruguay and Costa Rica share some similar traits with Chile. In all three countries, institutions and party competition matter, and they are the only Latin American countries with high judicial independence in a recent study by the Inter-American Development Bank. They are also the best-ranked countries in a more comprehensive index that measures government capabilities (i.e. congressional policymaking capabilities, party system institutionalisation, judicial independence, and civil service capacity) (Franco and Scartascini 2014). In Uruguay the judiciary is fully independent from the executive, and the Contentious Administrative Court (Tribunal de lo Contencioso Administrativo) is also strong (Buquet and Piñeiro 2014). During most of the twentieth century, a strong state exerted a monopoly of force throughout its entire territory. Despite featuring a decades-long patronage-based, clientelistic party system, it seems that corruption was never a pervasive practice in Uruguay. The clientelistic system really began to slowly change in the 1990s with rise of more programmatic parties and greater competition. Moreover, as a political strategy, clientelism could no longer be sustained economically. Anti-corruption legislation did not change politics but was the result of a political change that sought to strengthen the control of the administration and prevent corruption by regulating political practices and the bureaucracy in a new context of programmatic competition (Buquet and Piñeiro 2014).

Costa Rica is an example of a country that gradually developed and strengthened its institutions and mechanisms of accountability (Wilson and Villarreal 2015). This process started in the nineteenth century by giving autonomy to the judiciary from the executive branch and laying the basis for a system of separation of powers. Another important step was the country’s 1949 constitution, which created a weak presidency in regard to presidential powers, a strong and independent Supreme Electoral Tribunal, and new audit agencies such as the Office of the Comptroller General (Controlaría General de la República) and the Attorney General (Procuradoria General de la República). In 1989 the Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Court was created and became one of most powerful courts in Latin America. At the beginning of the first decade of the twenty-first century, the institutional framework of accountability was consolidated with additional laws. Moreover, citizen participation increased and restrictions on the media were lifted. Two former Costa Rican presidents (Miguel Angel Rodriguez and Rafael Angel Calderon) convicted of corruption have been given custodial sentences.

The Relevance of International Anti-Corruption Regimes

International assistance for democracy, the rule of law, the judiciary, and civil society has played an important role in democratic governance and accountability for the last three decades. International treaties are a major point of reference for reform-oriented actors inside the state apparatus as well as in civil society. Hence, while the levels of corruption in Latin America might not have greatly changed, the region’s tolerance of corruption has diminished, and the enforcement of existing legislation is increasing. Social change and new legislation that enhances both the transparency of public policies and the accountability of office holders are important drivers of protest (Casas-Zamora and Carter 2017). While both democratic and non-democratic governments have signed international anti-corruption regimes, democracy does make a difference. First, the chances are higher in democracies that international and regional treaties will be translated into national legislation. Second, democratic governments seeking re-election are more dependent on process-oriented patterns of legitimacy. Transparent and accountable procedures do matter.

Is the glass half empty or half-full? There have been great advances in the fight against corruption, but endemic corruption persists in many countries. While democracy – or democratic accountability – is not a cure-all for corruption, it does diminish the chances that corrupt practices will remain undiscovered. It is not by accident that Chile, Costa Rica, and Uruguay – which have been classified as the most democratic countries in Latin America for most of the twentieth century and the first two decades of the twenty-first century – are recognised as the least corrupt and least violent countries. At the same time, the deterioration of the standards of democratic accountability leads to the concealment of acts of corruption and subsequently to higher levels of corruption as the case of Venezuela illustrates. In parallel to the degradation of democratic controls in Venezuela starting with Hugo Chávez and culminating under Nicolás Maduro, Venezuela saw its ranking in Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index decline and became the most corrupt country in Latin America. While Venezuela is also involved in the Odebrecht scandal (and received with USD 98 million the highest sum of bribes from Odebrecht outside of Brazil), it is the only country where not the perpetrators but rather the journalists reporting about the scandal were prosecuted. In contrast, Chile reacted to several corruption scandals in 2014 and 2015 by the government and Congress approving several anti-corruption laws in 2016, including one on political party and campaign financing. Thus, how politics and the judiciary react to corruption scandals reveals a lot about the quality of democracy in a country.

Contrary to authoritarian regimes, democracies feature a specific variant of corruption: illegal party and campaign financing. This was a major ingredient in the Brazilian Car Wash and Odebrecht scandals. Illegal party and campaign contributions reflect the rising costs of elections. Therefore, the implementation and enforcement of laws that regulate party and campaign financing can be an important step to reducing corruption.

In most countries democracy has not reduced social inequalities. However, social inequality was a less contentious issue in the period of spectacular economic growth in Latin America that was fuelled by the commodity boom, which made possible active (but not re-distributional) social policies. Poverty rates decreased and the income sectors categorised as middle class increased; but corruption prevailed and intermingled with clientelistic practices. With the end of the commodity boom, poverty rates began to rise again, and the middle classes experienced or feared a loss of status. Although resources for clientelistic politics and campaign goodies have become scarce, there is still enough money for personal enrichment and to bribe politicians. However, these practices are now being confronted by angry and mobilised citizens.

In the long term the public exposure and criminal prosecution of corrupt politicians should strengthen democracy. But in the short term and medium term the consequences might be more ambivalent. Corruption scandals can diminish trust in political institutions and reduce support for democracy. While the electoral punishment of parties and politicians linked to corruption is understandable and justified, the loss of trust in politicians and the implosion of party systems might facilitate the rise of outsiders and populists. Guatemala is a relevant case with regard to this argument. There is no guarantee that replacing a discredited political elite will increase the quality of democracy. For example, the beneficiary of the mani pulite anti-corruption campaign in Italy was Silvio Berlusconi. Even though it is necessary to reveal corrupt practices and denounce corrupt politicians, the media and politicians have a special responsibility to not overplay or politically use the corruption issue, which might be tempting in electoral campaigns. The result of such actions might not be less corruption and a better democracy but the contrary.

International anti-corruption mechanisms such as the one provided by the G20 are important because governments bind themselves, at least formally, to transparency and accountability. Implementation, democratic control, and accountability need strong civil society actors and independent judicial institutions.

Footnotes

References

Aninat S., Isabel, and Ricardo González T. (2016), ¿Existe una crisis institucional en el Chile actual?, Puntos de Referencia, 440, Santiago de Chile: Centro de Estudios Públicos (CEP), www.cepchile.cl/cep/site/artic/20161007/asocfile/20161007155235/pder440_ianinat_rgonzalez.pdf (12 June 2017).

Buquet, Daniel, and Rafael Piñeiro (2014), Background Paper on Uruguay, ANTICORRP Project, Gothenburg: The Quality of Government Institute, http://anticorrp.eu/publications/background-paper-on-uruguay/ (12 June 2017).

Casas-Zamora, Kevin, and Miguel Carter (2017), Beyond the Scandals: The Changing Context of Corruption in Latin America, Washington, DC: Inter-American Dialogue.

Comisión Internacional contra la Impunidad en Guatemala (CICIG) (2015), El Financiamiento de la Política en Guatemala, Guatemala City: CICIG, www.cicig.org/uploads/documents/2015/informe_financiamiento_politicagt.pdf (30 May 2017).

Comisión para el Esclarecimiento Histórico (CEH) (1999), Guatemala: Memoria del Silencio, Guatemala City.

Corporación Latinobarometro (2016), Informe 2016, Santiago de Chile.

El País (2017), Qué es el ‘caso Odebrecht’ y cómo afecta a cada país de América latina, 17 April, http://internacional.elpais.com/internacional/2017/04/13/actualidad/1492099171_779545.html (12 June 2017).

Franco Chuaire, María, and Carlos Scartascini (2014), The Politics of Policies: Revisiting the Quality of Public Policies and Government Capabilities in Latin America and the Caribbean, Policy Brief, IDB-PB-220,Washington, DC: InterAmerican Development Bank.

InSight Crime (2016), Elites and Organized Crime: Introduction, Methodology, and Conceptual Framework, Medellin/Washington, DC: InSight Crime, www.insightcrime.org/images/PDFs/2016/Introduction_Section_Elites_Organized_Crime (12 June 2017).

Kaufmann, Daniel, Aart Kraay, and Massimo Mastruzzi (2010), The Worldwide Governance Indicators: A Summary of Methodology, Data and Analytical Issues, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, 5430, Washington, DC: The World Bank, http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1682130 (12 June 2017).

Llanos, Mariana, and Detlef Nolte (2016), The Many Faces of Latin American Presidentialism, GIGA Focus Latin America, 1, Hamburg: GIGA, www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publication/the-many-faces-of-latin-american-presidentialism (12 June 2017).

Narlikar, Amrita (2017), Can the G20 Save Globalisation?, GIGA Focus Global, 1, Hamburg: GIGA, www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publication/can-the-g20-save-globalisation (12 June 2017).

Navia, Patricio (2015), The Chilean Transition from Non-Corrupt Economic Underperformer to Most Developed and Least Corrupt Country in Latin America, Process-tracing Report on Chile, ANTICORRP Project, Gothenburg: The Quality of Government Institute, http://anticorrp.eu/publications/process-tracing-reporton-chile/ (12 June 2017).

Nicholson, Brian (2015), Brazil’s “Operation Car Wash,” London/São Paulo: International Bar Association (IBA), 8 April, www.ibanet.org/Article/NewDetail.aspx?ArticleUid=7960b146-65c4-4fc2-bb6a-c6fbb434cd16 (12 June 2017).

Padgett, Tim (2017), Brazil’s Car Wash Scandal Reveals a Country Soaked in Corruption, in: Bloomberg, 25 May, www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-05-25/brazil-s-car-wash-scandal-reveals-a-country-soaked-in-corruption (12 June 2017).

Ramírez R., Jorge, and Antonia Vinagre G. (2016), Encuesta de Corrupción 2016, Santiago de Chile: Libertad y Desarrollo, http://lyd.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/SIP-154-Encuesta-de-Corrupci%C3%B3n-2016-Julio2016.pdf (12 June 2017).

Silva, Patricio (2016), A Poor but Honest Country: Corruption and Probity in Chile, in: Journal of Developing Societies, 32, 2, 178–203.

United Nations General Assembly (2007), Civil and Political Rights, Including the Questions of Disappearances and Summary Executions, Report of the Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial, Summary or Arbitrary Executions, Philip Alston. Addendum Mission to Guatemala (21–25 August 2006), A/HRC/4/20/Add.2, http://repository.un.org/handle/11176/316980 (12 June 2017).

Weyland, Kurt (1998), The Politics of Corruption in Latin America, in: Journal of Democracy, 9, 2, 108–121.

Wilson, Bruce M., and Evelyn Villarreal Fernández (2015), Costa Rica’s Long, Incomplete Struggle against Corruption, Process-tracing Report on Costa Rica, ANTICORRP Project, Gothenburg: The Quality of Government Institute, http://anticorrp.eu/publications/process-tracing-report-on-costa-rica/ (12 June 2017).

General Editor GIGA Focus

Editor GIGA Focus Latin America

Editorial Department GIGA Focus Latin America

Regional Institutes

Research Programmes

How to cite this article

Kurtenbach, Sabine, and Detlef Nolte (2017), Latin America’s Fight against Corruption: The End of Impunity, GIGA Focus Latin America, 3, Hamburg: German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-52148-4

Imprint

The GIGA Focus is an Open Access publication and can be read on the Internet and downloaded free of charge at www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publications/giga-focus. According to the conditions of the Creative-Commons license Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0, this publication may be freely duplicated, circulated, and made accessible to the public. The particular conditions include the correct indication of the initial publication as GIGA Focus and no changes in or abbreviation of texts.

The German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) – Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien in Hamburg publishes the Focus series on Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and global issues. The GIGA Focus is edited and published by the GIGA. The views and opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the institute. Authors alone are responsible for the content of their articles. GIGA and the authors cannot be held liable for any errors and omissions, or for any consequences arising from the use of the information provided.